Caroline is standing by the north ball fields in Central Park in the snow. It is February. There is some kind of construction going on—or it was going on—the big yellow trucks have stalled, but still, she has had to circumvent them. She is walking southeast, toward Seventy-Ninth Street, through the park. It is freezing. The sky is pewter. The iron railings are so cold that she’s sure if she took her hand out of her glove and touched one, her finger would freeze in place. As it is, she’s stuck. Snow is drifting over her fur-lined boots. She is wearing a sheepskin coat and a fox-fur hat. Her aunt had given it to her. She said, when Caroline arrived at her door wearing the hat, “See, I was going to give it to the Guild for the Blind but then I thought, Caroline will wear it.” She is wearing it in the snow as she walks east and waits for Alastair to call her back on her cell phone, which she has set on vibrate and put inside her glove.

When Caroline first began to speak to Alastair on the phone thirty years ago, there were two ways to do it. There was a rotary phone in her tiny apartment that sat in a cradle like a blackened crab. When you wanted to make a call, or the phone rang, you picked up the receiver, and cradled it under your chin, placing one end by your ear and the other next to your mouth. Can I express the intimacy of this relationship, with the telephone? The round earpiece and the mouthpiece, identical, were perforated with tiny holes through which the sound entered and departed. The receiver was connected to the cradle by a black spiral cord. The cords could be different lengths. If the telephone had a long cord, you could walk around with the phone; if it was a short cord, you sat next to it while you spoke. In either case, you were tethered. The phone was attached to the wall at a special outlet, called a “telephone jack.” The plug was a little square of clear plastic. The round plastic dial of the telephone looked like a clockface. Like a clockface, numbers circled the dial. There were round holes in the plastic where you inserted your fingers to dial the numbers. Sometimes when Caroline was on the phone, she hooked her fingers into those holes.

The root of the word dial is dies, in Latin, day: dialis means daily. The medieval Latin is rotus dialis, the daily wheel, which evolved to mean any round dial over a plate. It is hard to convey now the heat of the old phone receiver, the curve of it on your mouth. If someone spoke into the receiver quietly, his lips would brush the tiny holes. There was the phone smell of plastic rimmed with overheated air. If you cut the cord, or the phone for some reason was yanked out of the wall, say, you saw that the wires inside the cord were brightly colored: blue, yellow, red, green. It was complicated, the business of talking. Caroline liked black phones. Usually, then, when the phone rang, it was Alastair, but to pick up the phone she had to be home.

The second way to make a call was to use a public telephone. There were phone booths on the corners of many streets. Always at the corner, never in the middle of the block. There were public telephones in drugstores and restaurants. You said to whoever was around, the girl behind the cash register, the man behind the counter: Can I use your phone? Or, if you wanted to use the telephone in the street and needed change, you asked if you could change a dollar for quarters, for the phone. The phone booths on the street were made of metal and heavy glass. Later in New York the phone booths became fewer in neighborhoods where drug dealers used them to schedule drops. Because of this you had to sometimes walk for blocks in the snow or the rain to find a phone.

It was warm in the phone booth and usually dry. Often people left things in phone booths: umbrellas, packages, wallets. They were distracted when talking on the phone, by what they were saying, or by what was being said to them. There was a bifold door to shut, for privacy. If you stayed too long in the phone booth, the windows fogged up; if you went inside after someone else had been inside a long time, it was foggy with their breath. The call was a dime, then it was fifteen cents, then a quarter. The public phones were rectangular, and there were three slots for coins on the phone, on the top; the slot for the dime was in the right upper corner. The receiver was connected to the phone by a cord. In the phone booth, the radius in which you could pace while you made a call was constricted; you shifted from foot to foot. In every case, no matter where you were calling from, there was a specified circumference, a radius, in which you could make a phone call, a certain distance and not more, from the place where the phone was connected to the earth, to the ganglion of wires that spanned out from the phone. Time was money. A long call cost more than a short one. When Caroline made a call from a telephone box, if it went on for more than three minutes the operator would come on the line and say, Five cents more, please. She scrounged for nickels, for dimes, later for quarters, in the pocket of her jacket, which had a hole. Coins slipped through and weighed down the lining as if she were planning to drown herself in the river.

When Caroline was a teenager, talking on the phone, it wasn’t unusual for the operator to break into a call: “Your father wants to get through on this line.” At the house where she went to the beach in the summer, there was a party line: five families on the road shared a number. If you picked up the phone and heard voices, the rule was: put it down. But everyone knew everyone’s business. Now there are ways to accomplish the same thing—the sense of being known; the world is a party line. Then people called “collect” when they did not have money for the phone, when they either did not have it or could not find the change. You could call the operator without a coin, and she would put the call through. In a “collect” call someone at the other end of the line picked up the receiver, and the operator said, “Caroline is calling, will you accept the charges?” What if he said no? The shame of it. There was no way to leave a message; it wasn’t until l986 that Caroline had an answering machine, which plugged into the phone and flashed a tiny little red warning light—then as now, there could be messages you did not want to hear. Along any road in the country the telephone poles stretched for miles, timber poles with wires looping over them, a chain stitch across the map, birds weighing down the wires, storms knocking them over. There were men whose job it was to repair those wires, sitting up on the poles. In the catbird seat. Up the mast. Gone now, the ruled paper lines the wires made in the air, music paper unfolding through the forests, on which voices sang, argued, planned, began, and ended things. A call from far away was a “long-distance” call.

Because phones were rooted to the spot, if someone called you and you picked up, they knew where you were, and if you did not answer they knew you were not there, which sometimes meant that you were not where you said you were. In Manhattan, the phone numbers gave it away: CHelsea 3, MUrray Hill 7. Caroline’s exchange was TRafalgar 7. You could not say you were one place and be in another; location services could not be switched off. Birds perched on the wires, black notes, arpeggios. Standing in the park by the ball fields, Caroline had her cell phone in her glove so that she would feel it on her palm if he called.

In the same few hundred square yards where Caroline is waiting for a phone call—at a time that has been prearranged, which turns out to be a time when Caroline, who has forgotten her morning schedule completely, had an appointment on the East Side and is now, instead, standing in the park, freezing, as she did not want to answer the telephone, if and when it rang, on the crosstown bus, windows steamy with condensation, or in a taxi—Alastair is crouched in the dark, forty years ago, writing his name in the frozen dirt by the ball fields with a stick. He is fifteen. He is wearing a down jacket which is too small for him and which has been handed down to his brother, but he does not want to give it up, because he likes the way it smells. The feathers are coming out, pricking the nylon with little quills. Underneath he has on his school button-down shirt. The shirt is white, and a little grubby. The tails are out. His sneakers are wet from the snow. At school, in French class, they had been shown a film, L’enfant sauvage. He is underdressed for the weather, but he is thinking about the naked wild child, Victor, in Aveyron. Did he never have any clothes? How can that be? He imagines being naked in the woods, the cold puckering his body. He has looked up the weather in rural France. At night in the forest, it can dip below freezing. Alastair imagines the boy digging a burrow in the earth and covering himself with leaves. At the Museum of Natural History, where he had been taken by his nanny two or three times a week in the afternoons after school, there is a room where you can see mice and shrews in their lairs under the snow. There are little tunnels under the earth that end in sometimes large, intricate rooms, filled with treasures and food, old nuts, wizened berries. In one the mouse looks frightened, as if he (or she: was it a girl mouse or a boy mouse?) had just fled from something menacing on the crust of the earth over the burrow. That is what it looks like, in the cross section of the glass: the crust of the earth. It is fraying a little, like an old piece of toast, the hard dirt over the burrow, frosted with snow. Alastair named the mouse Mike. “Ssh,” he said to Mike, touching his nose through the tempered glass. “How ya doing, Mike,” his brother, Otto said, leering, making scary faces at the mouse. But Mike, who was stuffed, did not move. There was no taunting him. They did not know then that later, at least for a little while, it would be Alastair who would save Otto. There was no saving Alastair. In the park in the cold at eight in the evening on a Wednesday night when he has told his mother he is working on his project about batteries or tree sap with his friend Jason on Central Park West, Alastair moves away from the ball fields—he is now about one hundred yards from where Caroline is standing—and into a grove of locust trees, which later would shrivel. In a storm in l996 they were toppled by the wind and then cleared. Locusts have shallow roots. Under the dirt the roots are in the way, the roots are everywhere. Alastair has no tool but his pocketknife. He is thinking about Mike, and the wild boy, and the shape of the burrow he would make, like a canoe in the dirt. He wants to take off his clothes and cover himself with leaves. In the morning, he will wake up and everything will be quite different. The park will no longer be the park but another place in the woods. He will be on an island that has not been discovered by anyone, full of leafy trees and streams, and he will go down to the stream and drink water by cupping his hands. Little fish will swim through his fingers. His grandfather walked with him in the woods in the summer. If he was lost, he was to listen for the sound of water. If you were lost at sea and saw a bird, that meant you were near land. In the winter though, Alastair thought, the water is frozen and there is no sound. When he passed it earlier in the day the Boat Pond had a lid of ice. His pocketknife is ineffectual, and he nicks the blade on a locust root or a stone. He pictures the burrow in his mind and unbuttons his shirt, his hands moving onto his skin.

Caroline is standing in the snow. She is so cold that the phrase freezing to death enters her mind. She is wondering if she is standing in exactly the right place. She knows about the burrow, and Mike the mouse. She thinks about what she knows about telephones. When she dials a number, does it shoot up to a satellite and then back down? Ordinary telephone conversations have always been mysterious to her. By ordinary she still means the kind of phone call that is attached to a wall by a black snake of wire. She likes picturing the conversations shooting over the tendrils. In the film Sunday Bloody Sunday, a triangle of lovers leave messages for each other along those wires. The conversations are irradiated by color, red, yellow, green. For a long time, Caroline thought that she was the single woman in that film who pours yesterday’s cold coffee into her cup, stubs out her cigarette on the carpet, and is thwarted and betrayed by the man with whom she is in love, a mophead—it’s 1971—who makes light-filled glass sculptures and who also loves an older man who has a surgery in Harley Street. But she is wrong. In the film, the mophead betrays both of his lovers, but she has not been betrayed, because in her own life nothing has been kept from her: she simply wants something that is not there, which she has been told is not there, but she thinks if she keeps wanting it, her desire will be like water on a stone, things will change. A form of magical thinking, making something out of nothing. Caroline knows and does not know this. But she is in hiding under the mask of the woman who stubs out her cigarette, because she is also the man who makes glass sculptures which fill at dusk with blue light, a person who loves two or even three people at once. (Or, she used to be that person. Now she is not.) What she likes is theater, the glass tubes filling with light. Alastair knows this about her; he also knows that he can stop her heart, which he is doing right now, because he has not called and she is freezing to death, one hundred paces from where there was once a grove of locust trees, where in another diamond of time, he is trying to cut a root with his penknife, a present from his uncle Link on his tenth birthday. Snow is falling down around both of them. A jangle of bells. There is nothing more beautiful, said Frank O’Hara, in a poem whose name she cannot now remember, a poem with long lines, like telephone wires, than the lights turning from red to green on Park Avenue during a snowstorm. Park Avenue is about a ten-minute walk from where she is standing, with her phone in her glove, if she could move. But she is like a figure in a snow globe.

(Now you ask, the first sign of you, to whom I am telling this story: Then, she also liked to talk on the phone? When I was a child, we used a gettone: “Non sei mai solo quando sei vicino a un telefono!” That was the slogan. “You’re never alone when you’re near a telephone.” Maybe yes, maybe no.)

__________________________________

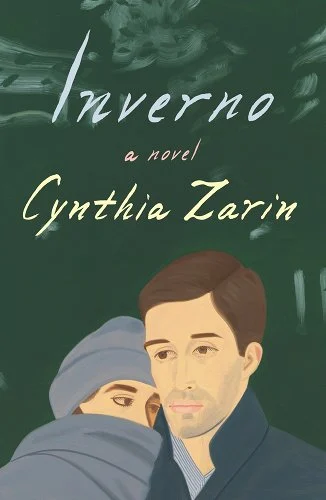

Excerpted from Inverno: A Novel by Cynthia Zarin. Published by Farrar, Sraus and Giroux. Copyright © 2024 by Cynthia Zarin. All rights reserved.