Inventing the Village: The Life and Times of the Jane Street Artists

On Nell Blaine and the Young Abstract Painters of Downtown New York

In the 1940s, art dealers interested in the abstract work the young downtown artists in New York City were making were virtually nonexistent. Dealers knew that collectors who wanted to buy modernist paintings were looking for famous Europeans. Other than participating in occasional competitions and juried shows, the avant-garde Americans were largely on their own. Founded in 1943, Jane Street Gallery (named for its location at 35 Jane Street, a former tailor’s shop in lower Manhattan) was a new concept: a cooperative, with the artist members doing all the work of painting the walls, hanging the art, publicizing it, and “sitting” the space when it was open to the public.

Hyde Solomon, Nell Blaine’s downstairs neighbor on 21st Street, invited her to join the group in 1944. Together with Al Kresch and Lee Bell (who joined slightly later), they formed the group’s nucleus of fiercely dogmatic abstract painters. “We were so excited, we really thought that was the gospel,” Nell said later. A writer described her single-minded way of talking about “the more or less absolute and unbending realities” in “terms closer to religion than anything else.” Most of the earlier Jane Street members, unpersuaded by the new doctrine, were gradually eased out. Taking their place was a raft of new painters, including Ulla Matthíasdóttir, Judith Rothschild, Sol Bloom, Sterling Poindexter, Frank Bacher, Ida Fischer, Frances Eckstein, and (in the gallery’s last days) Larry Rivers.

Matthíasdóttir, who had come to New York from her native Iceland in 1942, after studying in Paris, had a distinctive, radically simplified figurative style; her real subject was “the geometry of everyday life.” She imbued her vividly colored landscapes of restful scenes with an almost supernaturally alert quality, illuminated by the clear, bright light of her homeland. Little is known about Bloom (described in a listing of gallery members as a furniture designer) or Poindexter, an Abstract Expressionist from Texas. Bacher translated the Purist aesthetic into bold graphic compositions. During Rothschild’s Jane Street years, cut short in 1947 when she moved to California with her husband, she painted Cubist-influenced abstractions, the most successful of which are composed of flat, irregular shapes in unexpected color combinations.

Fischer, whom Nell described as “ebullient and vigorous,” prone to exaggeration but “a great storyteller,” had retired early from supervising music instruction at Washington Irving High School. On a round-the-world trip, she became fascinated with Chinese brush painting; later, she studied with Hofmann. In addition to her paintings, she made three-dimensional mosaic collages fashioned out of shards of broken cups, glitter, tinted plaster, and other objects.

Eckstein, a retired secretary, was Fischer’s life partner; unlike the others, she was self-taught and worked in what Nell called “a lyric primitive” style. Up-and-coming art critic Clement Greenberg predictably dismissed her paintings as “nice but irrelevant flower pieces.” In their fifties, decades older than the other members, the two women were prized for their wisdom, their “Old World culture,” and their food offerings. The “fabulous meals” Nell recalled eating at the Fischer-Eckstein home were five-course affairs that lasted for hours. Eckstein, who was as reserved as Fischer was talkative, made the desserts.

Nell, the gallery’s secretary (and subsequently coordinator—people sometimes referred to the “Blaine Street” Gallery), would recall this period as “an exciting time,” with lively openings and coverage from local media and national art magazines. The entire membership would visit an artist’s studio to determine whether he or she was worthy of joining the group. Nell later admitted that they could be “rather harsh,” rejecting “gifted people,” but “we wanted to keep the group small, at approximately ten members.”

Each artist paid about eight dollars, “which seemed a lot of money to us,” into a general fund for rent, printing of invitations, advertisements, and other costs. The gallery took only a 10 percent cut of sales, far less than commercial dealers. A patron system was eventually instituted; a $60 annual donation entitled the sponsor to choose a painting from a portfolio of work by all the members. Nearly every week, the artists would gather for a meeting. “But we weren’t good at business, any of us,” Nell said. “And we all had to learn to use the hammer and nails.” The result of this manual labor was a pristine space with white walls and gray floors.

Each member participated in annual or biannual exhibitions. Shows followed one another according to a brisk schedule, with only a few days’ downtime. During the first few months, critics were slow to respond, but people who lived and worked in the area stopped by frequently to look and ask questions. In an era when the people who attended art openings were usually in evening dress, an observer described the crowd at one of Nell’s openings as “young men with their collars open, long-haired girls in flat heels, a couple of smartly dressed middle-aged women, and two or three soldiers and sailors.”

*

Nell was so excited about a sketch she made in Hofmann’s class that when she came home, she told Bob, “I have to paint this right now!” So she used the first large surface she found: an eight-foot-tall theater poster she found lying on the street. Shown in a 1944 American Abstract Artists group exhibition, Great White Creature—a rhythmic composition of outlined black-and-white shapes, with a few touches of color—was favorably reviewed by Clement Greenberg in The Nation.

Peggy Guggenheim had rejected the painting for the 1943 Spring Salon of Younger Artists at Art of This Century, claiming that it was “too clean.” But the distinguished jurors had accepted it, and Greenberg and dealer Howard Putzel argued for its merits. In 1945, Nell’s work met with more favor from the doyenne of new art, whom she found “not an easy person to be around.” Her painting Blue Pieces was included in The Women, a summer exhibition of abstract and surrealist work by 30 mostly young and unknown women artists at Art of This Century.

The entire membership of the Jane Street Gallery would visit an artist’s studio to determine whether he or she was worthy of joining the group.

Influenced by the rhythmically scattered shapes in Jean Arp’s collages, Nell’s painting is a vertical dance of irregular blue, gray, and small red forms anchored by a black handlebar-mustache shape at the bottom. “I felt like I had become a painter, like from one day to the next,” she said later. For the first time, she was using “real colors” and was “really in touch with my feelings, putting them down directly.”

Having fallen under Mondrian’s spell, Nell wrote that when looking at his 1943 painting Broadway Boogie Woogie, “the eye responds in physical reflexes to the vibrating color transitions.” In this late work, crisscrossing bars of yellow interrupted by small rectangles of red, white, and blue reflect the stop-and- go dynamism of the city. Mondrian was a big jazz fan; by eliminating melody and replacing it with “dynamic rhythm,” this new music struck him as the equivalent of his painting.

For many artists of the period, rhythm was king. Hans Hofmann had written that it was “the highest quality” in art, and Jean Hélion had praised Seurat and Poussin for the rhythm of elements within their paintings and the way they directed the attention of viewers. Nell would take these influences to heart throughout her life; especially in her postpolio landscapes, her brushwork charged trees, flowers, and even distant mountains with a continuous rhythmic current.

The Jane Streeters sponsored a fund-raising jazz session at the Village Vanguard on a Sunday afternoon in June 1945, with tickets priced at $1.20. Hearing that Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker were going to play there one night, Nell and Al handed out flyers for their event to the queue of jazz fans. Waiting at the door after the concert, Nell walked up to Parker and gave him a flyer, assuring him that this was an invitation to listen, not to play. “She had that kind of nerve,” Al recalled. The group was also involved in other types of performance.

Jane Street artists designed the sets and costumes for the Provincetown Playhouse production of If Five Years Pass, Federico García Lorca’s 1931 play about young lovers, and mounted a concurrent exhibit of his drawings and manuscripts. During this period, the gallery was a Village institution, assured of having its events listed in The New Yorker and Cue magazine, the city arts and entertainment guide. Nell later said that part of the gallery’s mission was to show visitors “that the abstract artist is very sincere and is not trying to perpetuate a hoax.”

In November, Nell’s first solo Jane Street show elicited a tiny rave review in ARTnews, which noted that she was a 23-year-old native of Richmond, Virginia, and praised her “combination of simplicity precision and vitality.” The writer, painter Renée Arb, declared that “Mondrian would have admired . . . her compositions.” Nell was the youngest member of the group, a fact noted by a writer for the newspaper PM, who came to the opening and described her as “a thin, bobbed-hair girl with horn-rimmed glasses.” To this observer, Nell’s 15 paintings in the show looked like “crossword puzzles.”

Nell explained that the art was “concrete . . . as concrete as a leaf.” She was tossing out a term associated with Theo van Doesburg, author of a 1930 manifesto stating that art should make no reference to objects in the world, or to “sensuality or sentimentality.” But by comparing her own work to the concreteness of a leaf—nature always serving as her touchstone, even in an urban setting—she meant that an idea can have as much reality as something in the world.

Together with Rothschild and Fischer, Nell tried to steer the PM writer away from her preconceptions about art, including the then-current notion in left-wing circles that it should engage with social issues. The Jane Streeters’ emphasis on a “pure” art involved a total rejection of the literal-minded Social Realism that had dominated American art in the 1930s. Nell puzzlingly announced that painting “is social in itself ” and tried to explain the connection she saw between the Jane Street artists’ work and jazz. Fischer, probably aware of the writer’s bafflement, handed her a glass of sherry and exclaimed that the young people were “insane with life.” Clearly, she thought this was terrific.

The following year, in a published statement, Nell professed her delight in “giving the effect of a decorative pattern,” despite the effort it took “to make one form grow out of another with a natural flow, with twisting and turning complexities.” Her “strongest initial impressions” when conceiving a painting were “from nature itself.” It was extremely difficult to incorporate those “intervals, measures, and quantities” into her composition. The negative words she used to describe the process of translating nature to abstraction (“frustrating,” “dissatisfied,” “unequivocable [sic] demands”) suggest that this work went against the grain of her deepest artistic impulses. But her belief in the credo of the Jane Street group kept her from recognizing the problem. The Nell of 1946 would have been amazed at her admission, a dozen years later, that she could scarcely see a difference between artists who felt as she did and the Impressionists. “For me,” her future self would say, “the word ‘pretty’ is not a bad word.”

______________________________________

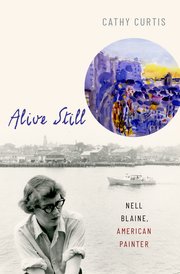

From Alive Still by Cathy Curtis. Copyright © 2019 by Cathy Curtis and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

Cathy Curtis

Cathy Curtis is the author of two previous biographies, Restless Ambition: Grace Hartigan, Painter, and A Generous Vision: The Creative Life of Elaine de Kooning. An alumna of Smith College and the University of California, Berkeley, she was formerly a staff writer at the Los Angeles Times. In 2018, Curtis was elected to a two-year term as president of Biographers International Organization (BIO).