Every so often, a book several years post-publication rises to such a level of popularity that it could only be the result of many thousands of quiet devotions: booksellers placing it front and center in shop windows, readers buying extra copies to give to friends, strangers recommending it to one another in crowded stores. In 2020, when Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s collection of essays about the bond between humans and the natural world—grounded in her perspective as a scientist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation—hit The New York Times bestseller list, it became one such anomaly and a landmark achievement for its publisher, Milkweed Editions.

At Lit Hub, we love independent presses; in a world where all commerce is constantly threatening to collapse into the same bleak mega-entity, indies are curated, careful, and passionate. Like so many others, my own relationship to Milkweed began with a copy of Braiding Sweetgrass, but the Minneapolis-based nonprofit has been publishing nonfiction, literary fiction, and poetry since 1980. Now, for the first installment of Interview with an Indie Press, a chance to hear more from the people who make up the field of independent publishing, some members of their team told me about maintaining a relationship with readers, working together during periods of political turmoil, and what having a mega-hit meant for their company. (Also, how to pitch them.)

*

What are some of the benefits to working at an independent press?

The best thing about Milkweed is that we’re just thirteen people who love great books and want to dedicate our time to supporting meaningful work. If there’s a change that we want to make in our publication process, we don’t have to jump huge hurdles to do it. Much of editorial and production work that I do is pretty procedural—there’s not much creativity in managing production schedules and metadata—but there are times when I talk with authors about editorial decisions that can have a significant impact on how a reader interacts with a book. In those moments, the author and I get to focus on what’s best for that specific text and we have the autonomy to make whatever changes feel most right. –Lee Oglesby, managing editor

What are some of the challenges to working at an independent press?

The small size of an independent press can be a challenge. Everyone on staff is managing at least a few different roles, with tasks that might extend beyond the responsibilities associated with that title at a different press. It gets busy sometimes! And of course, all of that is complicated by working remotely right now. Small presses are really personal workplaces, and there’s a definite loss when we can’t just pop by each others’ offices to ask a question or talk off-the-cuff about a manuscript we’re reading. –Lee Oglesby, managing editor

What are some of the biggest risks you’ve taken as a business? How did you navigate them?

The last few years have brought increasing sales and exposure to Milkweed, anchored by the astonishing ways that Braiding Sweetgrass continues to reach new readers. But that kind of growth brings risk, too. For example, selling more books obviously means printing more books; our first print runs have grown larger, and if a book is selling really well, we’ve begun investing in much larger reprints (the more books we print, the lower the unit cost per book). In many cases, however, booksellers can return unsold books, so these larger print runs do represent a leap of faith or a gamble. For a nonprofit, growth—not just in printing more books, but in publishing more books, in marketing those books, in increasing the size of our staff, and so on—is not without risk. But it’s a necessary and exciting risk, to try to be the partners our authors deserve. –Joey McGarvey, senior editor

Photo by Shannon Blackmer

Photo by Shannon Blackmer

Were there any titles in particular that were game-changers for your business?

Yes. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. This book has put Milkweed on the map in so many ways—most recently, it was the first Milkweed book in our history to be listed on the New York Times Bestsellers list, in February 2020 (the second was Aimee Nezhukamatathil’s World of Wonders, in December 2020). The fact that Braiding Sweetgrass landed on the New York Times Bestseller list five years after we published it in paperback is a rarity in our industry. Check out this week’s bestseller list and you’ll notice most (if not all) books listed were recently published, or they are books by celebrities.

Braiding Sweetgrass’s industry success has been a slow, grassroots build, led by independent booksellers and individual readers who have felt so deeply changed by Robin’s work that they press it into the hands of their friends, family, and community. In essence, Braiding Sweetgrass is a book about attention, written from the intersectional perspective of a writer who is a mother, botanist, professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. She writes with a deep reverence and respect for the natural world, weaving these multiple perspectives together, and too many readers to count have enthusiastically considered this book a “bible” of sorts, and a book to read slowly, to let seep into your bones.

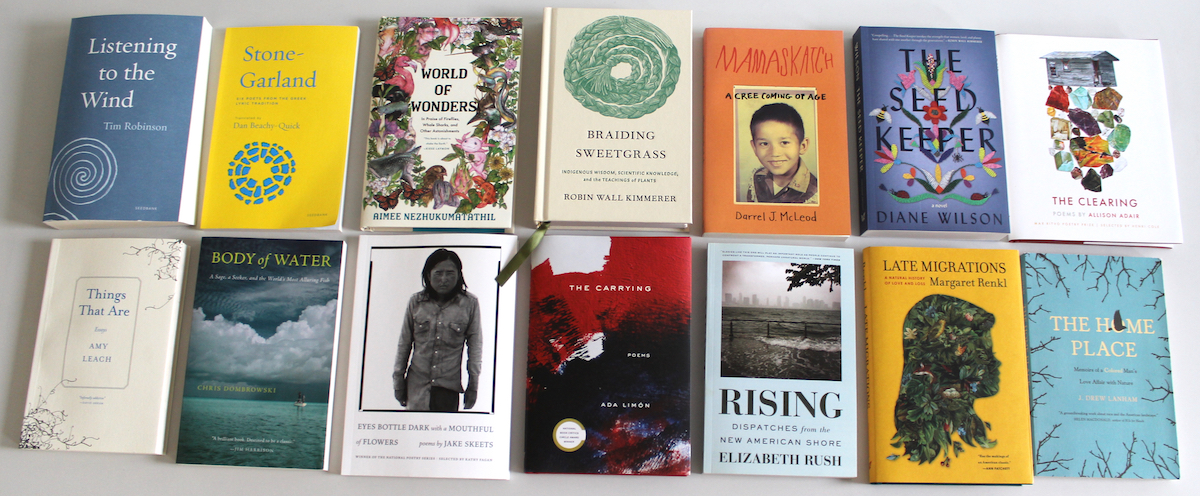

Braiding Sweetgrass has been a game-changer for our business because we have sold an incredible amount of copies—more than 460,000 as I write this—supporting both our publishing program and the author herself, but also because it’s opened up communication with our community. Readers write us emails. They find us on social media and tag us in their photos of Braiding Sweetgrass. They reach out to ask if they can republish excerpts on their blog. They choreograph dances inspired by Braiding Sweetgrass, paint, write songs, plant gardens, all of it. Our list has always aimed to amplify books that explore humans’ relationship with the nonhuman world, and for many readers, Braiding Sweetgrass is the door to other books we publish that do that in compelling ways: Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s World of Wonders, Elizabeth Rush’s Rising, Chris Dombrowski’s Body of Water, J. Drew Lanham’s The Home Place, Amy Leach’s Things That Are, Margaret Renkl’s Late Migrations, our Seedbank series. –Joanna (Yanna) R. Demkiewicz, marketing director

How do you get feedback from your readers?

We are a very chatty publisher, that is, we like to talk directly with our readers. Everyone is experiencing digital fatigue and oversaturation, but sometimes we’ll post something on social media—or in a newsletter—asking for feedback, and . . . we really mean it! We really want to hear from y’all! Readers reach out to us on social media (I look through all of our Instagram DMs, and I respond! Unless you’re a bot! Also unless you are trying to submit your manuscript! Manuscript submission 101, social media is not the place to do it), by responding to our newsletters, by emailing us directly, by sending us snail mail (yes, this sometimes still happens), by attending our events, by engaging with us during conferences and bookfairs, by donating to our org, by letting us know when they’re teaching our books in their classrooms, by sharing their favorite poems from Ada Limón, Jake Skeets, Allison Adair, the list goes on—and, sometimes, ya know, before the pandemic, and certainly after, by stopping by our offices and bookstore in the Open Book building in downtown Minneapolis and saying hi. –Joanna (Yanna) R. Demkiewicz, marketing director

Photo by Christian Dean

Photo by Christian Dean

How has the coronavirus crisis changed your work?

Like most businesses, the pandemic has changed the way we function as a unit—most of us are working remotely, and we’ve had to reconfigure our communication and workflow methods. Remote work has its benefits, but—obviously, I’ll speak for myself here—I miss my people and the spontaneity that occurs when you are sharing a workspace. Bookmaking is ultimately a people business, and we thrive off of each others’ energy. It’s almost impossible to emulate that in a virtual working reality. Covid has also hit a couple staff members personally, which has led to moments of vulnerability and openness across staff. I don’t feel I can reflect on the pandemic without reflecting on the impact of the former administration’s destructive and racist rhetoric and policies, as well as the national social uprising that was reignited—or simply ignited, for some folx—by the murder of George Floyd in our hometown, for some of us, just blocks from where we live.

All of this compounded has deeply impacted us on individual levels, trauma and grief and stress that cannot be unmarried from daily professional work. We’ve had to adapt in so many ways, and one way—that I don’t think is discussed widely in the industry—is by listening and stumbling and listening and encouraging staffers to put their health and community first. –Joanna (Yanna) R. Demkiewicz, marketing director

What are some projects you’re particularly excited about at the moment?

I’m particularly excited for books from two of our poetry prize winners, Michael Kleber-Diggs and Devon Walker-Figueroa, and for two nonfiction titles on our fall list, one from National Book Award-longlisted poet Victoria Chang and the other from Darrel McLeod, a sequel to his 2019 memoir Mamaskatch. In terms of projects I’ve been working on, 2021 will bring Diane Wilson’s The Seed Keeper in March—it’s a beautiful novel about homecoming and reciprocity and identity—and Margaret Renkl’s Graceland, At Last, a collection of her essays for The New York Times, in September. And then I’m excited about a bunch of forthcoming projects where new drafts should be coming in soon: Sangamithra Iyer’s gorgeous meditation on grief, inheritance, and nonviolence. A memoir from the poet Juliet Patterson, about a family history of suicide. An anthology, edited by Erin Sharkey, of Black writers in dialogue with archival objects that document the relationships of Black communities to the natural world. And Elizabeth Rush’s second book, about Antarctica, sea level rise, and community (in multiple forms). –Joey McGarvey, senior editor

How do debut authors reach/pitch you?

For poetry, we have four prizes that are awarded annually. For fiction and nonfiction, the best way is via an agent. We have occasionally opened for submissions in the past. Not for several years—we received an overwhelming response the last time—although I am hoping to open submissions briefly in 2021, just for manuscripts in our primary nonfiction category of writing about the environment and the natural world. –Joey McGarvey, senior editor

What’s another indie press you love/would recommend?

Catapult is always publishing something I can’t wait to read, and I’m fueled by the visionary books coming from Haymarket, AK Press, and The New Press. I’m also always interested in what’s going on with Black-led publishers. I currently have my eye on a couple of brand new presses—Bee Infinite Publishing and Vermillion Ink Press—but I would love to see more! –Lee Oglesby, managing editor