Interview with a Mad Cartoonist: The Time I Met Colonel Baxter

Somewhere in a Secluded Compound in South London...

As a young cub reporter I was given my first assignment—to interview the man they call Colonel Baxter. I packed my notepad and pencil and headed out for the grounds of the Baxter residence in a remote corner of South London. The taxi screeched to a halt at the perimeter fence. The driver refused my money and roared off into the murk.

I stepped forward to peruse the ring of antique Chinese cannons guarding the dilapidated topiary hedges that led to the first of a series of sentry boxes. After passing through several checkpoints, I found myself on the terrace of a crumbling Victorian mansion. I rang the doorbell and a butler ushered me into the entrance hall where an ornate crest announced tofu walk with me.

Within a matter of minutes, the great man appeared, removed his pith helmet, and extended his hand towards me. “Come in,” he announced, “and take a seat here.’’

I crossed the floor and following Baxter’s instructions took a seat in a wickerwork bath chair, which he assured me was an exact replica of the one in which Annie B. Hore traveled to Africa whilst writing her magnum opus, To Lake Tanganyika in a Bath Chair.

He motioned towards a large, slightly faded map of the world.

“This is Yorkshire!’’ Baxter bellowed, pointing to a charred oblong just above Oslo. I realized I was in the presence of greatness, or, at the very least, a maniac.

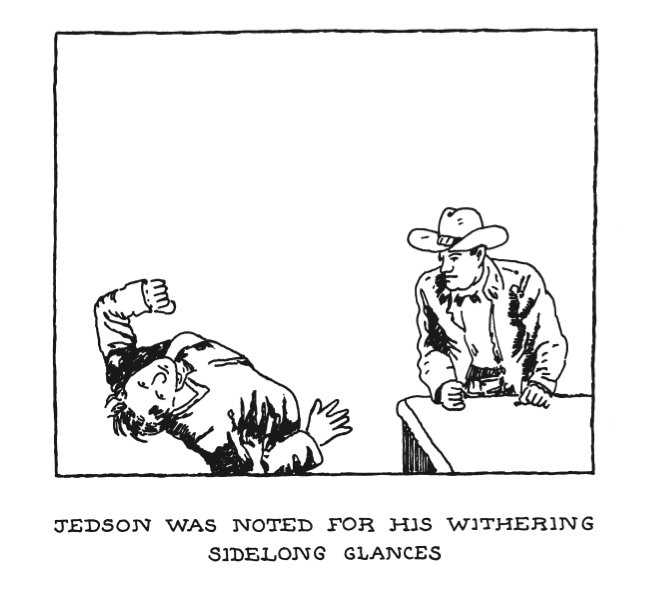

“Tea?’’ he continued, indicating the door to the library. Oak-paneled bookshelves were lined with leather-bound volumes bearing such titles continuously—newsreels, shorts, and, of course, B movies, which were almost always black-and-white cowboy films. The exploits of Tom Mix, Gabby Hayes, and Ming the Merciless took place in a world of fractured narrative: “we used to enter cinemas whilst the films were already showing, sit down in the middle of a film, watch it right through then on again till the part where you came in popped up!”

Looking to fill out my piece, I launched a softball inquiry: “Once you were grown, what came next?”

“I applied to art school in Leeds, desperate to shake off the monotony of school life. Once there, however, I discovered that most of the teaching centered around producing vapid versions of American Abstract Impressionism. I felt completely out in the cold and leapt eagerly into the clandestine, warm embrace of Dada and Surrealism. Years passed by in a flurry of chiaroscuro and vermillion before I left and made my way down to London on a makeshift sled. I discovered the work of Frank O’Hara and it wasn’t long before I was tumbling into the murky twilight world of poetry. I began to dabble in prose poems, picking up mimeographed poetry magazines in Charing Cross Road.

“I submitted some early attempts to Adventures in Poetry, a little magazine edited by Larry Fagin at the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church in New York City. I soon received an invitation to visit America.”

I interrupted, blurting out: “Was this what led you to become the first Baxter to cross the Atlantic?”

Colonel Baxter merely pointed to a black-and-white photo on his mantel: him, young and bare-chested, astride a flimsy-looking raft in the middle of the ocean.

“In 1974 I was invited over to read from my collected works at St. Mark’s Church before an audience of poets, painters, and filmmakers. I stood at the lectern, dressed in a tweed suit, and began to speak. People burst into spontaneous laughter. I had arrived.

“I showed around some of my little ink drawings and that same year had my first exhibition in the world at the Gotham Book Mart Gallery.”

My trusted pencil shot out of my hand in excitement: “Was this the point of the Baxter convergence of word and picture?”

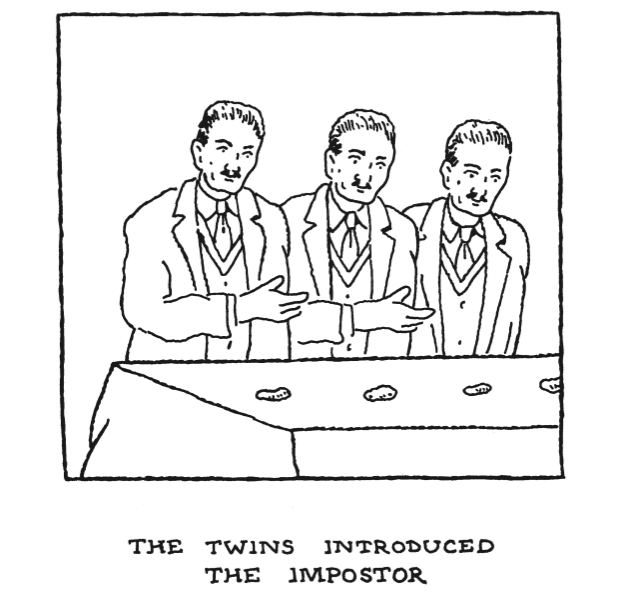

Baxter waved his hand towards two ornately framed booklets: “Gotham Book Mart published two little stapled-together magazines: Fruits of the World in Danger and The Handy Guide to Amazing People. Edward Gorey was a regular visitor and exhibitor at the Gotham Book Mart and he dropped by one of my shows there and bought a whole stack of drawings. He was very enthusiastic and it spurred me on: having your work bought by an artist you admire is as high as you can go on the Artistic Richter Scale.

“I was still having problems getting my work recognized in England and it took a brave Dutchman, Jaco Groot, to bring out my first book in Europe. Atlas was published in Amsterdam in 1979. Groot proudly sent out copies all across Holland. He sold six. He sat alone in his room, surrounded by trampled tulips, planning his revenge.

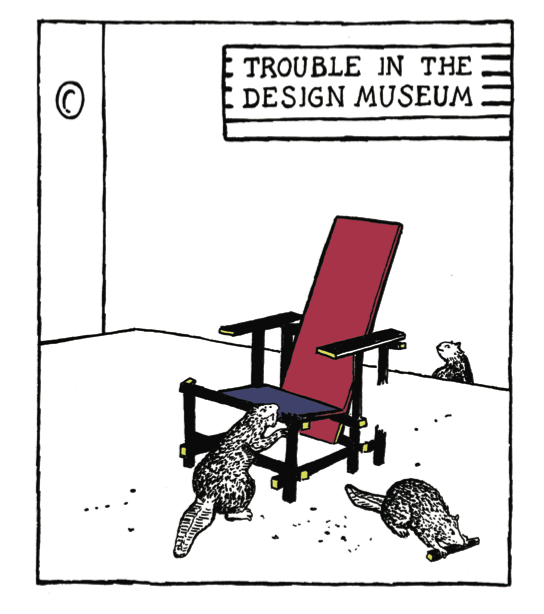

“Back home in London I was finally given the opportunity to unfurl my oeuvre at the Institute of Contemporary Arts and following that things really got out of hand. English and American publishers rushed to my door, the Tate Gallery bought a set of prints. My drawings appeared in The Observer, The New Yorker and the Ilkley Tortoise Quarterly. My art found its way into the homes of numerous dignitaries, submarine captains, notorious criminals, and John Cleese.”

He laughed at the thought of this, his voice echoing down innumerable hallways. I urged him to continue, clutching my pencil tightly to my chest. A tennis ball bounced in through an open window and rolled away into the darkness at the end of the library.

Baxter stepped forward and began. “Then gradually things began to unravel,” he explained. “My interest in marquetry was developing into an all-consuming passion, and it wasn’t too long before I found myself wandering alone in a wilderness of twine and metal hasps.”

He went on, setting the record straight on his mothball addiction and speaking in hushed tones of his incarceration in the mysterious ZIMMER 35 at the Furkablick Hotel high above Andermatt.

“It was quite a few years later that the French government discovered me and brought me back here.”

The next four hours in his company seemed to fly by, as I was regaled with tales of his time with the Royal Ballet and his mentor Sir Frederick Ashton, and the strange events of the Alpine Ascent with a team of Bulgarian yodellers intent on learning the secret of Baxter’s Triple Reverse Salchow.

As I finished scribbling and looked up, I found myself alone in the vast room. Colonel Baxter had disappeared, leaving only the scent of cordite and Earl Grey tea lingering in the air.

I grasped the sides of the bath chair before I lost consciousness. Two days later I found myself in a military hospital bed. A nurse was drawing a blanket over my arms. She handed me my notepad. It was blank apart from the letters U F O T scrawled across the cover. As she turned on her heel she looked at me and announced, “By the way, someone came in late last night and dropped this off for you.”

There on my bedside table was a slightly foxed edition of Shadow of a Gunhawk by Shane V. Baxter. The nurse crossed to the door and closing it behind her whispered, “I think this is only the beginning.” I switched off the light and drifted back into an uneasy sleep.

–Marlin Canasteen

Toledo, Ohio

From ALMOST COMPLETELY BAXTER. Used with permission of New York Review Comics. Copyright © 2016 by Glen Baxter. Introduction copyright © 2016 by Marlin Canasteen.

Marlin Canasteen

Marlin Canasteen is the author of The Balearic Trilogy and the acclaimed biography of the great American poet Richard Griffin. His books have been translated into fifteen languages. For many years he acted as Security Advisor at the Bolick Mandolin Conservation Society in Duluth, Minnesota. He currently resides in Toledo, Ohio.