Inside the Quest for Documents That Could Resolve a Cold War Mystery

Nicholson Baker the American Use of Biological Weapons

March 9, 2019, Saturday

In 2012, when I was hopeful and curious and middle-aged and eager for Cold War truth, I sent a letter to the National Archives, requesting, under the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act, copies of 21 still-classified Air Force memos from the early 1950s. Some of the memos had to do with a Pentagon program that aimed to achieve “an Air Force-wide combat capability in biological and chemical warfare at the earliest possible date.” This program, which began and ended during the Korean War, was given a code name: Project Baseless. It was assigned priority category I, as high as atomic weapons.

All twenty-one of these memos, numbered and cross-referenced, still exist, stored at the National Archives’ big building in College Park, Maryland—but they are inaccessible to researchers like me. At some point a security officer removed them from their original brown or dark green Air Force file folders—where they’d been stored alongside thousands of other, often fascinating documents that are now declassified and available to the public—and locked them in a separate place in the College Park building, in a SCIF, or Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility, where only people with security clearances can go. In place of the actual documents, the security officer inserted pieces of stiff yellow cardboard that say “Security-Classified Information” and “ACCESS RESTRICTED.” After filing the FOIA request, I waited. A month later I got a letter from David Fort, a supervisory archives specialist at the National Archives’ National Declassification Center. Fort said that my request letter had been received and that it now had a number, NW 37756. “Pursuant to 5 USC 552(a)(6)(B)(iii)(III), if you have requested information that is classified, it will be necessary to send copies of the documents to appropriate agencies for further review,” Fort wrote. “We will notify you as soon as all review is complete.”

After that came months of silence. A year went by. Then two. In May 2014, David Fort, now deputy director of the Freedom of Information division at the National Archives, wrote me an email. “Periodically our office contacts researchers with requests older than 18 months to see if they are still interested in us processing their requests,” he said. “If I do not hear back from you in 35 business days I will assume you are no longer interested and we will close your request.”

I wrote back that I was definitely still interested, and I asked Fort why it was taking so long. “Unfortunately,” he replied, “because of the large number of cases we receive there is a large delay in being able to process requests.”

In June 2016 I asked for another update. “We sent your documents out for a declassification review back in August 2014 and are still waiting for agencies to get back to us with determinations,” Fort wrote. “As soon as that happens we can send you the documents.”

Any document that a government takes special pains to keep away from historians, using a yellow access-restricted card, is likely to be revealing in some way.

Isn’t it against the law for government agencies to delay their responses to FOIA requests? Yes, it is: the mandated response time in the law is twenty days, not including Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays, and if one agency must consult with another agency before releasing a given document, the consultation must happen “with all practicable speed.” And yet there is no speed. There is, on the contrary, a deliberate Pleistocenian ponderousness. Some responses, especially from intelligence agencies, come back after a ten-year wait. The National Archives has pending at least one FOIA request that is twenty-five years old. “Old enough to rent a car,” said the National Security Archive, a group at George Washington University that works to get documents declassified.

So what should I do? Write more letters? Sue the Air Force? Sue the National Archives? Give up? Do these particular Pentagon memos even matter, when there are many thousands of declassified Korean War–era documents readily available to historians?

I did the simplest thing. I sent another email to David Fort. “Hi David—I hope all is well with you. I’m still hoping to see the twenty-one Air Force documents I requested in March 2012 (NW 37756). Seven years ago.” I deleted the words “seven years ago.” Then I typed them again. Seven years I’ve waited. I sent it.

For good measure, I also sent another email to David (who is a nice man) asking for information on a different request, a Mandatory Declassification Review that I’d submitted in March 2017. A Mandatory Declassification Review request, or MDR, is subject to different rules than a Freedom of Information Act request, and it can move along faster, or so I’ve heard. “Hi David—This MDR (# 57562, for two Air Force RG 341 documents from 1950) is now close to two years old. What should I do? Many thanks Nick B.”

Yesterday my wife, M., and I got two middle-aged, very small dachshunds from the Bangor Humane Society—possibly stepbrothers, one with long hair and one with short hair. They whimper and yowl and wag their tails so hard they make bonging sounds against the oven door. They’re rescue dogs. M. saw them on the Humane Society website.

*

March 10, 2019, Sunday

The two dogs slept in our bedroom last night. The cat, Minerva, is getting used to them. It was so cold outside at six this morning that one of the dogs, Cedric, simply stopped walking in the middle of the street. He wouldn’t move. I had to carry his shivering self home, while the other dog, whom we’re thinking of calling Brindle, or Briney, or Bryn, trotted along next to me.

This afternoon, I heard back from David Fort. Kind of him to respond on a Sunday. He’s in an awkward position, caught in the middle, with impatient inquirers like me on one side and huge, self-protective government agencies on the other. I interviewed him in the lobby of the National Archives Building in College Park two years ago. “What I tell researchers is we’re in a bind,” he said. “The National Archives has no legal authority to declassify records—with the exception of some State Department records if they’re prior to 1950.” Fort, who wears plaid shirts and is writing a book about the Battle of Bladensburg in the War of 1812, has reduced the backlog of open FOIA requests at the Archives. He tells his staff to be communicative with researchers. “There’s a lot of frustration out there,” he said. “All we can do is say we agree with you.”

The Air Force is causing the holdup now, not the National Archives, but the National Archives, which has taken physical possession of the documents, is the point of contact. Fort said in his email that the Air Force is “the worst” at responding to declassification requests. In my experience, the Central Intelligence Agency is the worst. But neither of them are abiding by the law. Let me explain why, out of the millions of pages of military records from the 1950s, these twenty-one withdrawn memos might matter. It’s not only because any document that a government takes special pains to keep away from historians, using a yellow access-restricted card, is likely to be revealing in some way. It’s also because these documents in particular may help answer one of the big unresolved questions of the Cold War: Did the United States covertly employ some of its available biological weaponry—bombs packed with fleas and mosquitoes and disease-dusted feathers, for instance—in locations in China and Korea?

The Pentagon instituted its secret crash program in germ-warfare readiness in the fall of 1950; six months later, in May 1951, North Korea’s foreign minister, Pak Hon-yong (variously spelled Pak Hen En and Park Hun-young), made a formal complaint to the United Nations, announcing “a new monstrous crime of the American interventionists.” During their rapid retreat from North Korea, Minister Pak alleged, U.S. troops had deliberately spread smallpox.

The American press barely noticed. “Foe Charges Use of Bacteria” was the May 9, 1951, headline of a tiny United Press wire service article, printed on an inner page of The New York Times, surrounded by ads for budget shoes from John Wanamaker, nylon robes from Gimbels, and Mother’s Day hats from Bloomingdale’s. “The Communist North Korean government demanded today that General of the Army Douglas MacArthur and Lieut. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway be tried as war criminals for using ‘bacteriological warfare’ in the Korean War.” That was all it said. The next day, a brief story in the New York Herald Tribune, republished in The Washington Post, began: “A charge that U.N. forces employed bacteriological warfare in North Korea, which caused 3500 smallpox cases between January and April, 10 percent fatal, was filed here today by the North Korean Communist Foreign Minister, Pak Hen En.”

The charge was not lightly made, and it deserved more coverage. Minister Pak had sent a long cablegram to the United Nations, where he had no standing, because only the South Korean half of that artificially divided country was allowed to be a member of the General Assembly. What Pak said was that the Americans, with the help of the Japanese, had spread an epidemic disease—he called it smallpox—during their retreat late in 1950. “It has been established by medical experts that the American troops retreating from North Korea in December last year resorted to spreading smallpox infection amongst the population of the areas of North Korea temporarily occupied by them, trying by this means to spread a smallpox epidemic to the troops of the People’s Army and Chinese volunteers,” he said. Outbreaks of the epidemic had flared simultaneously in Pyongyang and several other provinces “seven or eight days after their liberation from the American occupation.” By mid-April, Pak said, there were more than 3,500 smallpox cases, and 10 percent of patients were dying. “Areas which have not been occupied by the Americans have had no cases of smallpox,” he said, and he charged that on General MacArthur’s orders, the mass production of bacteriological agents had been carried out in Japan. “It has been reported in the press that MacArthur’s staff spent 1,500,000 yen on the manufacture of the bacteriological weapon, having selected the Japanese government as intermediary in the placing of orders.” This was a sign, Pak said, of the bankruptcy of the U.S. ruling circles’ aggressive adventurist policy. The Americans believed that they would undermine the Korean people, but they had miscalculated. “Criminal methods of war do not intimidate the freedom-loving Korean people and will not save the American interventionists from inevitable defeat.”

American authorities “flatly denied” the charges, according to the Associated Press, attributing the epidemic to an ineffective disease prevention program.

In February 1952, Foreign Minister Pak charged that the Americans were at it again. “According to precise information of the command of the Korean People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteers,” Pak said on the radio on February 22, 1952, “the American aggressive troops with effect from January 28 of this year have been systematically dropping a large number of infected insects from aircraft on to our troop positions on our rear, and these insects are spreading the bacteria of infectious diseases.” The American imperialists were, according to Pak, “waging bacteriological warfare in our country on a wide scale,” and they were doing so with the help of Japanese “myrmidons,” whose crimes were known to the world.

“In the name of the Chinese people, before the peoples of the whole world, I accuse the government of the United States of the criminal use of bacteriological weapons in violation of all principles of humanity.”

The Associated Press briefly covered Pak’s speech. “North Korea’s foreign minister has accused United Nations forces of raining ‘fleas, lice, bugs, ants, grasshoppers and spiders’ onto North Korea,” the article said, as reprinted in the New York Herald Tribune on February 23, 1952. “The Communist premier said former Japanese generals who were known to be specialists in germ warfare are assisting Americans in Korea.” United Press covered the speech at greater length, saying that the North Koreans claimed that “deadly insects” were dropped on nine flights between January 28 and February 17. United Press identified the insects as “black flies, fleas, and bed bugs,” which delighted an editor at the Waterloo Daily Courier, in Waterloo, Iowa (home of a large John Deere tractor factory), who put the story on the front page: “Reds Claim U.S. Planes Drop Bed Bugs.” Some versions of the UP article carried an added paragraph: “The claim recalled Communist charges of more than a year ago that U.S. planes dropped potato bugs on Czechoslovakia to destroy crops.” The insects were wrapped in paper bags or paper tubes, the Communists claimed.

From there the accusations grew in volume—gradually at first, but rising to an amazing steady onslaught, a “torrent of propaganda,” as United Press called it. On February 25, 1952, Chinese prime minister Chou Enlai charged that President Truman had ordered the germ-warfare attacks. “Refusing to acknowledge their defeat, during the course of the talks the American imperialists are, on the one hand, making use of all kinds of shameful delaying tactics with the aim of preventing the success of the talks, and on the other, are conducting a cruel, inhuman bacteriological war,” Chou said. The Americans were trying to extend and prolong the Korean War, he said, and they sought to destroy the People’s Republic. “In the name of the Chinese people, before the peoples of the whole world, I accuse the government of the United States of the criminal use of bacteriological weapons in violation of all principles of humanity.”

Initially The New York Times ignored this second round of charges, as if the editors had made a decision not to publicize such absurdities, but on February 25, 1952, the Times gave it a paragraph on page 2, reprinting an Associated Press version of the story: “The Peiping radio continued last night its new and violent accusations that the United States was using germ warfare in North Korea. Allied officers consider it possible that the Communists are plagued by epidemics and are trying to account for these to their own people.” (Peiping is Beijing.)

On this same day, February 25, 1952, at a meeting of the Central Intelligence Agency, Frank Wisner, director of covert operations, gave a report to Allen Dulles and other department heads on the progress of an unspecified “deception matter.” Two whited-out paragraphs follow shortly afterward. (CIA redactionists now mostly use white rectangles, rather than black rectangles, to withhold lines of text.) Also on this day, February 25, the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the Joint Advanced Study Committee’s recommendations on biological warfare. The committee recommended that the United States “be prepared to employ BW whenever it is militarily advantageous.” “This action removed BW from its unfortunate association with the ‘retaliation only’ policy which governs CW,” said a later memo. General Hoyt Vandenberg, chief of the Air Force, wrote an upbeat assessment of biowar prospects. “The research and development program is being expedited,” he said, “and certain offensive capabilities are rapidly materializing.”

On February 26, 1952, Kuo Mo Jo (Guo Moruo), a famous Chinese poet and political figure, president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese People’s Committee for World Peace, issued a statement: “In violation of all principles of human morals, the predatory American troops in Korea are carrying out bacteriological warfare,” Kuo said. “They have repeatedly scattered bacteria-infected insects in large quantities on the front line and in the rear of the Chinese and Korean people’s troops. The vileness of this inhuman crime of the American invaders has shaken the entire Chinese people and provoked unprecedented indignation.”

A spokesman for the Eighth Army in Seoul denied the germ-warfare charge the next day. “It is not true as far as this headquarters is concerned,” the spokesman said. “We have at no time or in any place engaged in any such activities.”

“Unofficially,” reported the Associated Press, “Allied officers said Red charges indicated epidemics, perhaps the bubonic plague, were sweeping North Korea and the Communist propaganda machine was trying to blame it on the U.N. Command.”

On February 28, Beijing’s English-language broadcast led with five separate stories about bacterial warfare. “This is an abnormally heavy dose even for Peiping propaganda casts,” said the Associated Press. One of the Beijing news stories recalled an incident in 1940, “when countless civilians in Chekiang province died of bubonic plague spread by the Japanese invaders.”

On March 4, 1952, The New York Times published an article about Secretary of State Dean Acheson’s repudiation of what he called “this nonsense about germ warfare in Korea.” The headline was “acheson belittles foe’s germ charge.” Acheson, patrician, big-eyebrowed, Groton and Yale educated, issued his statement: “I would like to state categorically and unequivocally that these charges are false,” he said. He had, he added, proposed an impartial investigation into the allegations by the International Committee of the Red Cross; the Communists, fully aware of the falsity of their charges, had refused. “The inability of the Communists to care for the health of the people under their control seems to have resulted in a serious epidemic of plague,” Acheson said. “The Communists, not willing to admit and bear the responsibility that is theirs, are willing to pin the blame on some fantastic plot by the United Nations forces.” Acheson extended the State Department’s “deepest sympathy” to those who were sick or suffering.

This provoked several apoplectic articles in People’s China, an English-language magazine published in Beijing. A lead editorial asked: “Who will believe Acheson, that old apologist for the most abominable atrocities of napalm bombing, the wholesale razing of defenseless hamlets and murder of populations in Korea, when he brazenly claims that the United Nations forces have not used any sort of bacteriological warfare?” Paul Ta-kuang Lin, a Canadian-born associate of Chou En-lai who had studied at the University of Michigan and Harvard, wrote: “With the sneering cynicism so characteristic of the present leaders of American imperialism, Dean Acheson on March 4 denied the charges of bacteriological warfare and affected ‘deepest sympathy’ for the ‘very sad situation’ of Korean people, which he based on ‘Communist inability to care for the health of the people under their control.’ The people of the world know well by now what Acheson’s denials are worth. They will throw the grim facts in Acheson’s face and demand an accounting on the severest terms.” The facts were incontrovertible, Lin said—there was the evidence of eyewitnesses, and of scientists. “The case against the American war criminals, however, is not based on such evidence alone,” Lin continued. “It lies in the nature of American bacteriological warfare as an integral part of the long range policy and strategy of aggression by the Washington Government. When Acheson affects a shocked attitude as if he never heard of bacteriological warfare, he is flying in the face of facts which have long been a matter of record in the U.S. itself.”

There are thousands of still-classified documents that could help us understand what happened.

Month after month, the germ-war outcry continued, from news sources in North Korea, China, and Russia—claims that civilians were suffering from fevers in towns near the Yalu River, and that masses of feathers and clusters of out-of-season insects and dead voles were appearing in the snow after a single American plane had passed overhead. The allegations were countered by denials, back and forth, repeatedly, angrily. The Communists assembled a group of international lawyers (“ jurists”) to investigate the charges, and then they convened an International Scientific Commission—six scientists, one of whom was Joseph Needham of Cambridge University. And they publicized dozens of confessions by American POWs, who said they had received germ-warfare training, had flown bacterial bombing missions, and were sorry.

Either the Russians, the Chinese, and the North Koreans had planned and executed a gigantic coordinated hoax involving thousands of people, a “big lie”—as the American government said they had—or there was a core of truth to their claims.

Which is it? We may never have incontrovertible proof. But there are thousands of still-classified documents that could help us understand what happened.

One of the access-restricted documents I’d like to see—that I asked to see seven years ago and have a legal right to see—is a memo sent on August 15, 1951, from “Wilson” to “Grover.” Its file designation is “471.6 BW Munitions.” (BW is the abbreviation for biological warfare; the number 471.6 corresponds to bombs and torpedoes in the Defense Department’s old decimal filing system.) Wilson is probably Roscoe C. Wilson, an Air Force general who’d been involved in the Manhattan Project during World War II and had commanded a bomber wing in Japan in 1945. In 1951, General Wilson was head of the Air Force’s Office of Atomic Energy, or AFOAT, which held within it a team of about a dozen Pentagon planners and promulgators called AFOAT BW-CW, whose job was to advance the cause of biological and chemical weaponry. (“Accelerated, aggressive, if not drastic, action is indicated,” one Air Force general wrote in December 1951.) This memo comes from their office files, now held at the National Archives.

Grover is Orrin Grover, a West Pointer and math whiz who was head of a different and more CIA-tinctured group at the Pentagon—the Air Force’s Division of Psychological Warfare, which in addition to psychological warfare was concerned with “unconventional warfare and special operations.” (The CIA and the Air Force worked closely together in the 1950s: Hoyt Vandenberg, the chain-smoking, movie star–handsome Air Force war hero, became, in 1946, the second director of central intelligence, even before there was a Central Intelligence Agency to direct; then, in 1948, he became secretary of the Air Force.) General Grover, who had a pencil mustache and looked a bit like David Niven, was a believer in “thought bombs”—i.e., propaganda leaflets and radio and other forms of aerially delivered psychological warfare—but as the files show he also took a special interest in the E-73 feather bomb, an adapted propaganda bomb in which disease spores were mixed with turkey or chicken feathers and stuffed into the bomb’s compartments in place of leaflets.

Details of the design of the Air Force’s E-73 feather bomb have been declassified since the 1990s, so that’s probably not the reason this document is being held back, year after year, in the National Archives’ SCIF. The document is withheld, possibly, because it describes some actual plan that involved the covert use of biological munitions in Russia, China, or North Korea. By 1951, the Central Intelligence Agency was a giant, far-flung, undersupervised aggregation of subversionists, paramilitary trainers, plague propagators, and nerve warriors, all operating under the bland cover of “intelligence gathering”—and one of their major targets was the Russian wheat crop.

Or perhaps the document is restricted because it refers to the work of the Japanese germ-warfare scientists of World War II—Ishii Shiro and the men of Unit 731—whose research had been, since 1947, exploited, applied, and extended by American disease-breeders and disseminationists at Camp Detrick, a large biological research unit in Frederick, Maryland, an hour from Washington, D.C., founded in 1942 and overseen by the Army’s Chemical Corps. Camp Detrick was where the feather bomb was prototyped, with CIA money. Or—another guess—the document was withheld because it’s about the testing of some other type of biobomb, perhaps one that holds insects. A 1950 annual report of the biological department of the Army’s Chemical Corps says: “An investigation is being conducted in the Medical Division, Chemical Corps, with Biological Department support, to study the potential use of arthropods to transmit viral and bacterial agents of significance for biological warfare. The program during the past year has included development and assay of attractants for flies, and both field and library studies of Arctic mosquitoes.” So the memo from Wilson to Grover could be about a potential bug bomb. Or it could be about very little. It could just be that the security officer who filled out this yellow placeholder card on September 25, 1991—his or her initials are “DC”—decided that the memo held “sensitive information” and withheld it from history for reasons that we will never be able to divine when it is finally declassified. That happens, too.

__________________________________

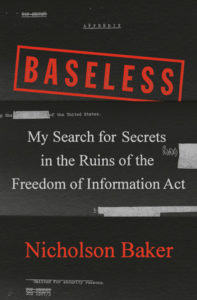

From Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act, by Nicholson Baker, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Nicholson Baker.

Nicholson Baker

Nicholson Baker is the author of ten novels and numerous works of nonfiction, including The Anthologist, The Mezzanine, and Human Smoke. He has won the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Hermann Hesse Prize, and a Katherine Anne Porter Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He lives in Maine with his wife, Margaret Brentano; both his children went to Maine public schools.