Inside the Long Friendship of James Merrill and

Elizabeth Bishop

“Your long wonderful letter is here today.”

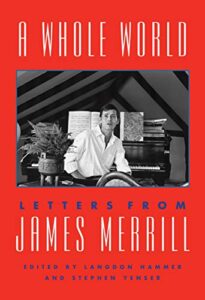

Featured photo by Jill Krementz

James Merrill and Elizabeth Bishop became friends when Merrill asked her out to lunch in 1948. He expected to spend the meal praising her poetry, but when he told her how much he admired it, and she said thank you, and no more, he realized they would not become friends by talking about literature.

They do talk about literature at times in their long correspondence, as for example in this letter, where Merrill ventures a reading of Bishop’s great poem “At the Fishhouses.” But here, as usual, literature is braided with life, with gossip and jokes, glancing confessions, and hugs and kisses to friends. When he says, “Everything flows in 2 directions,” he is referring to the way perception works in Bishop’s poetry. But it is also a good description of their lively correspondence.

Merrill, who was fifteen years younger, idolized Bishop. Their friendship was somewhat formal to begin with. Writing to Bishop, Merrill signs himself “Jim,” rather than “Jimmy” or any of the other names his closest friends called him. But the friendship deepened in 1970 when he traveled to Brazil to visit her in Ouro Preto, near Belo Horizonte (the “BH” in this letter). It was rare for an American writer to visit Bishop in Brazil, and Merrill found his idol in a state. He had to take her place when she was too drunk to host the party she had planned for him. She was reeling from the breakdown and sudden departure of the American woman with whom she had been living. She was in mourning also for her Brazilian partner of many years, Lota de Macedo Soares, who died from a drug overdose in 1967.

This was “the bad spell” Merrill mentions in this letter, written after he returned to the United States. By this time Bishop was on her way to the United States too: she had been hired to replace Robert Lowell, temporarily, in his poetry writing courses at Harvard. Lowell had left his wife Elizabeth Hardwick. Merrill doesn’t know about this turn of events when he writes to Bishop, but he knows Hardwick and Mary McCarthy are in intensive consultation: “WHY?,” he asks in caps.

August 1970 was a turning point for Bishop, effectively marking the end of her life in Brazil, and the start of a last chapter in Massachusetts, her birthplace. Now she and Merrill would see each other regularly in Boston, New York, and Stonington, Connecticut, where Merrill lived.

Merrill’s letter refers to many friends he and Bishop shared, including the duo pianists Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, and the photographer Rollie McKenna. Merrill’s multiple Davids are hard to keep track of: his friend David Kalstone, one of the best critics of Bishop’s poetry; David McIntosh, a painter; and David Jackson, Merrill’s lifelong partner. Merrill writes, “I’ve begun to juggle my life, instead of holding it, however clumsily, in both hands,” but in truth it was always that way for him. His poems emerged from the juggling, alongside a great many funny, fluent, loving letters like this one.

–Langdon Hammer, editor

*

To Elizabeth Bishop

Vassar

29 August 1970

Stonington, CT

Dear Elizabeth—(don’t be alarmed, it’s only me),

Your long wonderful letter is here today; and I fling some words onto the page hastily, otherwise you will have left for BH and Frisco . . . I’m so happy to have word (a postcard would have sufficed, seeing how pressed you must be); and to know that you’re all right; and that the bad spell is over. You must never never never say that you aren’t sensible. Actually I think we are both enormously sane; you even more than I, at least at the present writing. These last weeks things have happened which leave me feeling that I’ve begun to juggle my life instead of holding it, however clumsily, in both hands; always some spinning object in the air which must be beyond me if I’m to manage at all. And I dream of getting AWAY; then I think of you there in your house, with Eva + the laundress, and Adam whom I never saw. I don’t know—these inklings of what life has to be; Randall J was so good at expressing them [in the margin: and questioning them, both.]

“The public was fan-tast-tic: pure mass hypnosis; everyone suddenly knew more [about] art + the world than ever in life before.”

. . . I’m writing too quickly to say anything, forgive me. David Kalstone + I have been having (to us) fascinating conversations about your work. He thinks he is going to do an essay on Pastoral (his field) and “At the Fishhouses”; and all at once we were talking about this knowledge from the sea; the seal’s curiosity making the singer sing— each learning from the other; the dredge in “The Bight” rummaging below the surface . . . DK’s point had to do with the reversal from the classical pastoral in which the poet addresses himself to a world; now, so often, the world is asking, touchingly or otherwise, to be seen (Stevens’ sparrow who says “Bethou me . . . “). Everything flows in 2 directions, Heraclitus might want to say if he were still alive; or as you put it, “up the long ramp descending into the water . . .” In Boston the other day I squeezed my way through 8 rooms of Andrew Wyeth who is, I suppose, the first major American in the arts since Frost. The public was fan-tast-tic: pure mass hypnosis; everyone suddenly knew more [about] art + the world than ever in life before. Boys of 9, freckled + 50 lbs overweight were talking about Thoreau. Old ladies slow on their feet + feeling the heat were saying, “Look at those red-rimmed eyes in that picture. Can’t you tell how hard that woman’s life has been?” As with those Frost audiences towards the end, you felt that the people had complacently come to show themselves to the work, rather than vice versa; and, while the experience wasn’t wholly agreeable, it seemed to be of a piece with this two-way flow. (I bought Simone Weil’s Gravity + Grace that day; opened it to such an astonishing paragraph that I’ve not dared to look in it since.) I’d been up in Hancock NH (4 miles north of Peterborough) with my friend David McIntosh, a painter from Santa Fe who has taken a vacant apartment downstairs for the rest of the year. His health is very bad; he’s lost the sight of one eye, and even the best hospitals in the country are stumped. Rollie + he are great friends, too. In Hancock my brother has a big piece of wilderness, barns, ponds, beavers + cranes. Perhaps 2 cars a day pass by. David did watercolors, I sharpened a pencil or two; we’d meet for lunch by the pond and swim with a pair of black retrievers who were so smitten by the end of the afternoon that they lay in front of the house after our return, howling in the most heartbroken way. Beautiful wildflowers, berries, deadly nightshade, etc. I hope you’ve received Hine + Howard. I’ve spoken to Bill Meredith about your reading at Conn College. He is technically director of that program, but will be in Pittsburgh all this semester. Now that I’ve heard for sure that you’re coming I’ll speak to him (next week) and set up a date some Fall weekend (they usually have their readings on Sunday afternoons)—a date which you can surely change if you like. He said they could pay $250—not bad for the stir. [in the margin: Offhand I can’t answer your questions about Logue, etc. And wouldn’t know whom to ask—a weekend, with all the experts in their cabins, far from the telephone . . .]

Please call from Boston as soon as you’re there. I must go to NY Sept 29 for 3 or 4 days (David Jackson and my mother are returning, separately, from Europe on the 30th); but will [be] back here by Oct 3. Perhaps the following weekend you’d like to come down? Oct 9???

Oh—no, the New Yorker has never reviewed any of my vols of poems since Louise B did a really withering paragraph on First Poems. A phrase from it stuck in my mind; everything, she said, “smelt of the lamp”—which I finally “did something with” in my Eros + Psyche poem from Nights + Days; so I guess I’m more grateful to her than not. I’d be entirely thrilled to have you mention me; but what most pleased me in all your letter was when you said that reading me had made you feel like writing. More to the point, then, to put off the review indefinitely; a poem written in its place would do us all much more good.

Yes I’d heard about Cal; but no details; only that, for some odd reason, Elizabeth + Mary are far away in Castine with their heads together—WHY? I’ve been given a xerox of the (unrevised) proofs of the new Berryman book—loaned it rather by Frank Reeve whom JB is prone to telephoning late at night. It is a new phase, very uneven, at first glance now dull, now upsetting, with the unexpected flashes one expects. He refers once or twice to your loss of Lota (“Miss Bishop’s friend has died”) and, in a brief survey of those of whom he is proud to be a contemporary, he mentions you as writing “a mean lyric” (quoted from memory, but, I think, accurately). Which last may swell your autumn enrollment . . . ?

I’ve got to stop! You’ll lose patience. Besides, tonight is a great party in the defrocked Baptist church next door; and one wants to lie down beforehand. Bobby + Arthur sent love over the phone. So do I. Please congratulate José Alberto on his prize. I remember his purple trousers. And dear Linda, my love to her. The batida cartoon has us all giggling. Of course I’ll return to Belo H.—with his family-size bottles of meat-tenderizer, enough for a whole decade of armadillos . . . Do I remember why you are suing Lilli? Give her my best, and Donald Ramos, and Eva. And the cat.

Until very soon, mucho, no, muinto (muito?) amore—

Jim

__________________________________

A Whole World: Letters from James Merrill, edited by Langdon Hammer and Stephen Yenser, is available via Knopf.

James Merrill

James Merrill is one of the foremost American poets of the later twentieth century, was the winner of two National Book Awards, the Bollingen Prize, the Pulitzer Prize, and the first Bobbit Prize from the Library of Congress. He published eleven volumes of poems, in addition to the trilogy that makes up The Changing Light at Sandover, as well as two plays, two novels, a collection of essays and interviews, and a memoir. He was a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. LANGDON HAMMER is the Niel Gray Jr. Professor of English at Yale University. His books include James Merrill: Life and Art and Hart Crane and Allen Tate: Janus-Faced Modernism, and he edited the Library of America volumes of Hart Crane and May Swenson's poems. He writes about poetry for The New York Review of Books, The Yale Review, and The American Scholar, where he serves as poetry editor. STEPHEN YENSER's volumes of poems are The Fire in All Things, awarded the Walt Whitman Award by the Academy of American Poets, Blue Guide, and Stone Fruit. Distinguished Research Professor at UCLA, he has written three critical books including The Consuming Myth: The Work of James Merrill, coedited with J. D. McClatchy five volumes of Merrill's work, and annotated a stand-alone edition of Merrill's The Book of Ephraim.