Inside the Days, Hours and Minutes Leading Up to the Hiroshima Bombing

Iain MacGregor on the Preparation and Aftershocks of the Attack That Marked the Beginning of the Nuclear Age

“Right after we dropped the bomb, I felt much the same as I do now except that I hadn’t drunk as much coffee that morning.”

–Commander Paul Tibbets Jr.

*Article continues after advertisement

General Curtis LeMay had now been with the 509th Composite Group (the weapon delivery arm of the Manhattan Project) for a few days, having landed on Tinian Island on August 3, 1945. There was a reason the general was making a personal, somewhat unusual visit to the island airstrip. He was carrying sealed orders for Lieutenant Colonel Paul Tibbets, commander of the 509th: “Special Bombing Mission No. 13.” Within it, and what he would discuss with the strike leader, was the authorized date for the attack on Japan with a nuclear weapon. The date agreed was August 6, and LeMay discussed with Tibbets the targets that had been assigned:

Primary—Hiroshima urban industrial area

Secondary—Kokura arsenal and city

Tertiary—Nagasaki urban area.

The order confirmed that no friendly aircraft, “other than those listed herein, will be within a fifty-mile area of any of the targets for this strike during the period of four hours prior to and six subsequent to strike time.”

Thirty-two copies were distributed to commands in Guam, Iwo Jima, and Tinian. Tibbets locked his copy in the office safe and then departed with LeMay to inspect Little Boy, nestling on its cradle in the Tech Area. The most important commanders on the base were barred from entry by one vigilant MP who demanded LeMay first hand over his cigars and matches. Earlier that morning, the senior military men and scientists on Tinian had agreed that Tibbets’s weaponeer for the mission, Captain William S. “Deak” Parsons, would arm the device in flight. Parsons had made a convincing case that to have the bomb armed before actual takeoff risked destroying the whole island should the Enola Gay suffer a malfunction and crash—as so many other B-29s had over the past months. The fear of catastrophic engine failure haunted all of them. Parsons would crawl to the bomb bay early in the flight to insert one of the uranium plugs and the explosive charge into the bomb to fully arm it.

In the baking midday heat, Tibbets had decided to go and judge the finished livery he had instructed the crews to paint on the newly christened Enola Gay. He admired his mother’s name in a bold black font beneath the pilot’s side of the cockpit. The imposing bomber, along with the other six that would accompany him on the mission, had their distinctive 509th arrow inside a circle insignia removed and replaced with a simple large black R. Tibbets worried that any deviation might lead an inquisitive Japanese interceptor to attack them. He now oversaw the plane being towed to the loading pit. He studied the weapon as it was slowly and carefully hoisted into the bomb bay of the Enola Gay by the technical staff.

Wiping the sweat from his forehead with his handkerchief, Tibbets could make out a variety of scrawled messages; one declared, To Emperor Hirohito, from the Boys of the Indianapolis. He recognized the tribute to the old battleship that had delivered parts of the bomb to Tinian. He took in the familiar dimensions of the plumb-shaped, gunmetal-gray ordnance: nine hundred pounds, twelve feet long, a diameter of twenty-eight inches, and sharp tailfins protruding. Tibbets later recalled in his memoir: “Looking at the huge bomb with its blunt nose and four tail fins, I wondered why we were calling it ‘Little Boy.’ It was not little by any standard. It was a monster compared with any bomb that I had ever dropped.”

The weather was perfect for a bombing run. He could see the coastline of Japan from a hundred miles away. By the time they were just seventy-five miles away, he could clearly see Hiroshima itself.

Later that evening, Tibbets called the crews together for a briefing. Theodore Van Kirk recalled: “We knew this was going to be a very important thing because they had guys with Tommy Guns out situated around the briefing hut. Who’s going to go on the mission, what the course is going to be, what the bomb heading is going to be and all that kind of stuff. Then they tell us to go and get some sleep and they’ll call us at 10 PM for the final briefing, the final breakfast and then we’ll go down to the airplane. How are they supposed to tell you you’re going out to drop the first atomic bomb and then go and get some sleep is absolutely beyond me. I know Tibbets didn’t sleep, and I know Ferebee didn’t sleep, and I know I didn’t sleep, because we were [all] still in the same poker game, and I don’t even remember who won!”

The crews had been informed that there would be two deviations from the procedures they had practiced. Tibbets had decided to change the Enola Gay’s call sign from “Victor” to “Dimples.” Just as he feared an air attack from enemy interceptors, so he fretted that they might also pick up his call sign via radio traffic. Secondly, now that Parsons had won his argument to arm the bomb in flight, Tibbets announced they would remain at an altitude of five thousand feet for the first leg of the flight. Parsons needed as much stability in flight as possible to do the job safely. He assured the crews precautions had been taken with the US Navy for a thorough safety net of vessels and submarines situated at points along the route below, to retrieve them should the Enola Gay or any other plane on the mission ditch in the sea.

At 11 PM, the three crews were brought together one final time for Tibbets to address them: “Tonight is the night we have all been waiting for. Our long months of training are to be put to the test. We will soon know if we have been successful or failed. Upon our efforts tonight it is possible that history will be made. We are going on a mission to drop a bomb different from any you have ever seen or heard about. This bomb contains a destructive force equivalent to twenty thousand tons of TNT.”

Van Kirk remembered their final orders. “We were given instructions that when we dropped the bomb…we have to do it visually, otherwise take it out and drop it into the ocean. Do not bring it back with you. That’s all there was to it.”

As if to confirm the scientific nature of the mission, what resembled welder’s goggles, but fitted with Polaroid lenses, were then distributed to all of them. Professor Ramsey from the Manhattan Project reassured them that they were to prevent blindness from a bomb flash that was intended to be brighter than the sun. An hour later, they all made their way to the mess hall to eat a breakfast of eggs, sausage, rolled oats, pineapple fritters, apple butter, and plenty of coffee. While his men ate, Tibbets quietly, without them noticing, tucked away a packet of cyanide pills into his breast pocket.

The roar of engines in the distance told them the three weather planes—Straight Flush, Jabbitt III, and Full House—had successfully taken off. They would fly an hour ahead of the strike force to report back weather conditions for a visual bomb-drop over the principal targets. At 1:45 AM, they finished their last cup of coffee, and Van Kirk found himself in Tibbets’s jeep as they drove down to the flight line. “We got down to the airplane and that was our first surprise. Lights beamed all over the plane and people were interviewing the crew, taking photographs and movies. We hadn’t expected this. All the [senior] command of the Manhattan Project [were present] to record the moment for historical purposes. The Enola Gay was heavily ladened (over 15,000 pounds more than usual): the bomb, plus gasoline stored in the rear bomb bay to balance out the aircraft.”

Takeoff was scheduled for 2:45 AM in the dark, humid night, watched by a crowd of at least a hundred officers and men, as well as reporter Bill Laurence. Tibbets watched his crew board the plane. His copilot, Captain Robert Lewis, his best friends, bombardier Major Ferebee and navigator Captain Van Kirk, radarman Lieutenant Jacob Beser, weaponeer Navy Captain Parsons, assistant weaponeer Lieutenant Morris Jeppson, radar operator Sergeant Joseph Stilborik, tail gunner Staff Sergeant George Caron, assistant flight engineer Sergeant Robert Shumard, radio operator PFC Richard Nelson, and flight engineer Technical Sergeant Wayne Duzenbury now boarded the Enola Gay to write their names in history. Van Kirk recalled with a smile how his friend ensured no one was mistaken about who was running this mission, even if this wasn’t his usual plane to fly: “Tibbets scolded Lewis: ‘Keep your damned hands off [the controls]. I’m flying the aircraft!’”

Tibbets focused on the 8,500 feet of coral runway ahead, checked in with his crew to confirm all was ready, wiped the sweat from his palms as he gripped the stick, and gunned the mighty Wright Cyclone engines. All his training, all the sacrifices, and all the secrecy came down to ensuring he got the Enola Gay off safely and didn’t join the blackened wrecks of B-29s he could make out in the artificial light lying close by.

“Dimples Eight Two to North Tinian Tower. Ready for takeoff on Runway Able.”

Less than a second later came the reply: “Dimples Eight Two. Dimples Eight Two. Cleared for takeoff.”

Special Bombing Mission was now a go!

As he lifted the Enola Gay into the night sky, three more B-29s roared behind him, making ready to follow suit. The Great Artiste, commanded and piloted by Major Charles Sweeney and Lieutenant Charles Albury, would carry the observation equipment, No. 91 (later renamed Necessary Evil), flown by Captain George Marquardt, was kitted out to photograph the detonation, and Big Stink, piloted by Lieutenant Charles McKnight, would act as standby until they reached Iwo Jima, where it would land.

Aboard the Necessary Evil in his navigator’s seat was Lieutenant Russell Gackenbach, plotting the course where the three strike planes would coordinate their flight paths once weather conditions over the target sites had been confirmed. He recalled: “At Iwo Jima, we met each other, formed up in the V-formation and flew up to the IP. At the IP, Enola Gay and the Great Artiste flew in toward the city of Hiroshima.”

Long after Tibbets had launched the Enola Gay from the Tinian runway, right across all wards of Hiroshima city, teams of air defense officers and fire wardens had been in action following the false air raid warning. The “B-sans” had bombed Ube City in Yamaguchi Prefecture, ninety miles to the southwest of Hiroshima, which had brought the city’s fire defenses to high alert. Mayor Awaya had risen from his bed to take reports from his head of fire department, before he, his wife Sachiyo, and his eldest son Shinobu tried to settle down again by 3 AM. Luckily it had not woken their young granddaughter, Ayako. Across the city, many citizens followed the mayor’s example and returned to their homes in the early morning sunrise, while a few remained at their posts and continued to work their shift.

Tibbets’s B-29 crews knew it was going to be a long flight: six hours and fifteen minutes out and six hours and ten minutes back. With little to worry about as the Enola Gay cruised along at five thousand feet, still some miles to the south of Iwo Jima, his own crew relaxed as best they could. Or at least most of them did. For Theodore Van Kirk, the strain began almost immediately as he studied his charts. “I was the only guy working the whole time! If you had seen my log, I’m recording our instrument readings and location every fifteen to twenty minutes. The way navigators screwed up was that they didn’t keep up with the airplane. I didn’t want to just keep up with it, I wanted to keep ahead of it.”

As they approached Iwo Jima, Parsons and Jeppson announced to Tibbets it was time to arm Little Boy. He nodded his consent and looked down at Iwo Jima, easily spotting the distinctive shape of Mount Suribachi. He immediately thought about the thousands of US Marines who had died taking the island before they had finally managed to plant the flag at the summit. The two weaponeers disappeared to crawl back to the bomb bay. Though he had spent hours practicing the routine of taking out the green plugs to insert the red plugs to make the bomb live, the US Navy captain sweated as he did it for real. Checking that the colors were correct, he patted the steel plum and gestured to Jeppson that they should return to the cockpit. Van Kirk looked up from his charts as the officers reappeared from the bomb bay: “Parsons sat next to me monitoring the console,” he recalled. “I asked him, ‘What happens if any of the green lights come on?’

“He replied: ‘We’re in a helluva lot of trouble!’”

Parsons leaned next to Tibbets’s seat and informed him the bomb was now good to go. Tibbets seemed more relaxed than he’d ever seen him. Indeed, he was. The mission was for now going according to plan. He pulled back the controls, and the Enola Gay steadily climbed to her operational height of thirty thousand feet. The weather was perfect for a bombing run. He could see the coastline of Japan from a hundred miles away. By the time they were just seventy-five miles away, he could clearly see Hiroshima itself. Van Kirk continued:

“We wanted to bomb on a heading of 270 degrees as Ferebee wanted to hit the target. Escaping fast with a tailwind wasn’t an option. Accuracy was. It didn’t make any difference [anyway] as the winds from the south were very light. We sat on the bomb run for a long time. I shouted to Tom, ‘If we had sat on a bomb run this long in Europe, we wouldn’t be here.’”

Everyone in the cabin was now laser focused, and chatter throughout the plane had stopped. Their training kicked in as they prepared to release Little Boy. Tibbets broke the silence to remind his crew to put on their goggles. They would lower the Polaroid dark lenses once the bomb was on its way. Studying his own charts aboard Necessary Evil as it flew behind Tibbets, Russell Gackenbach watched his own crew don their goggles as his plane made a 360-degree turn lasting six minutes, plus fifteen seconds. “When we came out of that turn, we were headed directly for Hiroshima.”

The main subject of conversation as they flew back home was the end of the war with Japan. How could they withstand such a weapon? They could not visualize the destruction they had left in their wake.

To the north, two miles from Aioi Bridge, eight-year-old Howard Kakita was excited he might enjoy a day off school if his grandparents allowed. Perhaps he and his brother might even catch sight of a plane flying overhead. They had forgotten their lives back in California, where the boys had been born before the war. Howard’s extended family had several relatives who had made the decision in the 1920s to build their future in the United States. His parents had made the fateful decision to send their two young sons to their parents in Hiroshima just before the attack on Pearl Harbor as an extended holiday. Now, four years into the Pacific war, they lived in a Midwest internment camp as “enemy aliens” while Howard and his brother had grown up fully Japanese.

Like thousands across the city, the alarms that had warned of an impending air raid had caused Kakita’s family to seek shelter in their purpose-built shelter his grandfather had decided to construct in the courtyard. “During that night, there had been an air raid siren, and my grandmother woke us up to take shelter. Once the all clear had been given, we came back out of the shelter and went to bed. It was a Monday morning with beautiful weather. Our grandmother got us up at around seven o’clock in the morning to go to school. On the way to school, we saw a bunch of children coming back toward our direction and saying that school was cancelled because there’s still some enemy aircraft in the neighborhood. So, we came home and changed into our play clothes.”

Sumiko Ogata’s family home had been pulled down by the firebreak squads, forcing them to relocate closer to the river in the city center. Her new home was only several hundred yards from Little Boy’s designated target. Her father had been called up to fight in China in August 1941 and had not been home since. Sumiko’s mother had departed the day before to visit her oldest brother, who had been evacuated, leaving her sister in charge of the house, Sumiko, and her two younger brothers (five and three years old). She had been given the day off from school due to feeling unwell and from lack of sleep from the air raid sirens that had gone off earlier that night.

Thirteen-year-old Setuko Thurlow had been assigned with other classmates as part of the Student Mobilization Program to Field Marshal Hata’s military headquarters. Her primary function every day was to decode messages in a two-story old wooden school now called the Bureau. She worked on the second floor, surrounded by dozens of others, all listening to radios, their pencils and paper at the ready to take down any enemy communications they might pick up. A lot was American music, or civilian chatter, but sometimes they would detect radio tests made by incoming B-29s. These would be passed on urgently to the air defense headquarters. The morning had started like most others, her team listening intently to a morning pep talk from the Army major in charge of her section. She noticed many of her young friends stifling yawns. She, too, felt incredibly tired, having had been deprived of sleep by the B-San, and was now dreading the long day ahead as the morning’s heat increased.

Seventeen-year-old Mitsuko Koshimizu had rushed to her class at Jogakuin College of Economics. Her daily commute on the train from her family’s home at Iwakuni, twenty-five miles to the southwest of the city, had been frustratingly delayed. She wasn’t to know that the enemy plane flying over that had set off the alarms in the city was the B-29 weather plane scouting for the Enola Gay. The summer heat had been oppressive, and Mitsuko had decided to wear her pale purple short-sleeved uniform instead of the heavier black long-sleeved version. Despite the lighter clothes, she had sweated running to college to register, before heading to chapel while most of her friends stayed in class. She took her place at the back and settled down to pray. She then headed to the first class of the morning with her friends.

Fusako Nobe had left for school from his family home in Teppocho in Naka Ward, to the east of Hiroshima Castle. Like everyone else, he was relieved the air raid warning had been lifted. Although he was still a college student, he had been working at the factory as a mobilization workforce student. On August 1, he had been given permission to start school again and had begun studying hard. The morning service had just finished, and, along with dozens of other students, he exited the assembly hall to start his day. He recognized the tune the piano played in the background as the students chatted and walked into the morning sunshine.

Having completed her second year at high school, Junko Yoshinari was now part of the mobilization student workforce, working at the Ujina Railroad Station some miles outside Hiroshima to the southeast. As the war worsened, her office had become unsafe due to enemy bombing raids, and her administrative department had been relocated in the city, transferring to one of the school buildings at Hiroshima Jogakuin, east of where Little Boy was heading. With the morning heat already intense, she had decided not to walk and instead take a streetcar to her job. Arriving, she greeted some workmates as she went to the relevant desk to sign in for work.

Far up in the clear blue sky, Tom Ferebee was crouched in the nose of the Enola Gay, studying the city below through the bombsight as he worked to correct the plane’s drift. Talking with Van Kirk, as they had on countless missions, they conferred notes and then agreed that at their speed of 330 miles per hour, Ferebee should adjust the bombsight by eight degrees to allow for the Enola Gay’s drift. They were now ten miles away from the target and had engaged the autopilot, which now guided by the bombsight was leading them to the aiming point. Suddenly, Ferebee announced he had sight of the familiar T-shaped Aioi Bridge. He was certain; they had studied it dozens of times back at base. At that signal, Ferebee was in charge. Tibbets let go of the controls. It was now a matter of seconds.

Behind them, in the Necessary Evil, the team of observers positioned themselves, ready for the detonation. Russell Gackenbach recognized the signal they were all waiting for: “We were in the bomb run, and the radio went dead. That was done on purpose. When that radio went dead, it told us ‘Bomb-bay doors are open, bomb is gone.’ At that point, the scientists aboard our plane pushed a button on a stopwatch. So many seconds later, he pushed a button on the camera, which is mounted on our bomb site. And then they proceeded to take the film.”

Theordore Van Kirk suddenly felt the Enola Gay surge upward as their nine-hundred-pound bomb left the bomb bay. “Immediately Paul switched off the autopilot and started to go into the turn to get away from it—160 degrees to the right. Steep as you can make it. Pushed the throttles all forward, put the nose down to get enough speed to get away in the forty-three seconds at which the bomb would reach its altitude where it would explode.”

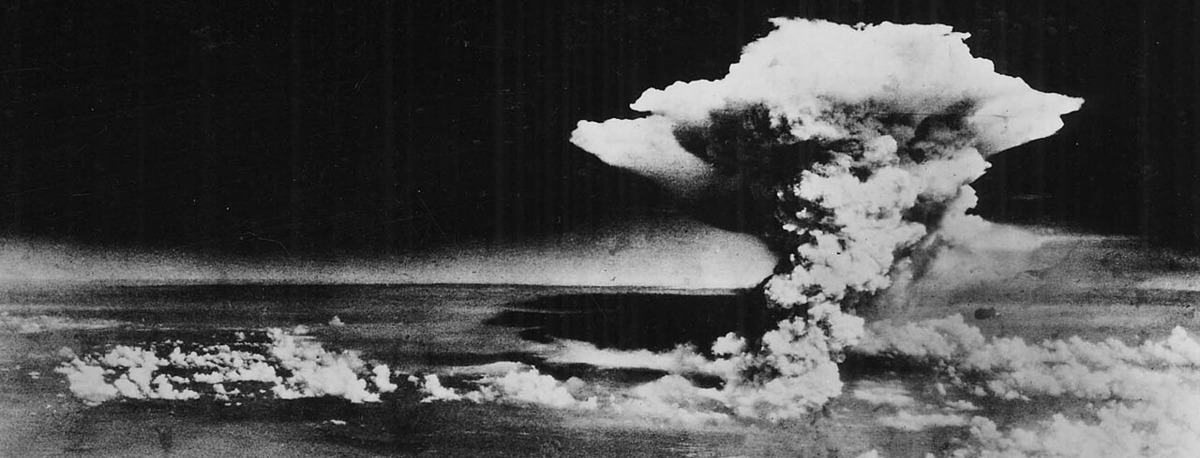

Little Boy hurtled toward earth, heading for the Aioi Bridge. At five miles down, the bomb’s fin radar system activated the detonator. At 8:15 AM, some forty-three seconds after Ferebee had dropped it from the Enola Gay’s bomb bay, the weapon exploded at 1,890ft above the ground. Tibbets and his crew were by then approximately six miles away, having turned away as instructed by Oppenheimer. Ferebee’s aim, however, had been off, missing the bridge by approximately eight hundred feet. The atomic bomb detonated instead above the Shima Surgical Hospital. It didn’t matter for the men, women, and children of Hiroshima within the blast radius; the effect would be the same.

Van Kirk recalled, “Everyone in the airplane didn’t have a watch, they were counting, ‘1001, 1002, 1003, etc.’ I think we had concluded it was a dud, as it seemed to be a long forty-three seconds. Then suddenly, there was a bright flash in the air and very shortly after, the first shockwave hit the Enola Gay. The sound was worse than the shockwave. It sounded like a piece of sheet metal snapping. Somebody onboard [mistakenly] called out ‘flak!’ but George Caron in the tail gunner’s position confirmed it was a shockwave, and another one was about to strike, though less intensity than the first.

“It was then that Bob Lewis [exclaimed] second statement in the log [probably once he got on the ground at Tinian—‘My God, what have we done?’—it was a better quote]. What he actually said in the aircraft was: ‘Look at that son of a bitch go!’”

Aboard the Necessary Evil, Russell Gackenbach felt the sonic boom. “The echo just bounced off the nose of our plane because of streamlining. The other two planes were heading away from the blast, so their tails felt the blast. As a result, [the Enola Gay] were rocking for a little while until their tail gunner says, ‘Here comes another sonic bomb.’”

“We looked now at what had happened,” recounted Van Kirk.

“The first thing you saw was that there was a large white cloud over the target, well above our altitude of 45,000 feet already and rising. At the base of the cloud, the entire city was covered in a thick blanket of smoke, dust and anything that was kicked up by the blast. It was obvious we weren’t going to make any visualization down there. We did not circle the city. We flew a southeast quadrant of Hiroshima and then flew home.”

Observing from the Enola Gay at twenty-nine thousand feet, as Tibbets steered the plane away from the blast, Flight Sergeant George Caron looked at what they had “achieved.” The planned coded message was now transmitted:

82 V 670. Able, Line 1, Line 2, Line 6, Line 9.

Clear cut. Successful in all respects. Visible effects greater than Alamogordo. Conditions normal in airplane following delivery. Proceeding to base.

The shock waves that struck the plane had spooked the crew until Caron reassured them it wasn’t enemy flak. All of them had declined to don their metal protective vests. Tibbets, Ferebee, and Van Kirk were very familiar with them from their countless bombing runs in Europe, where they had contended with strong antiaircraft fire. Right now, on a gloriously sunny morning over Hiroshima, there were no Japanese interceptors to be seen at the altitude they were flying. Nor would there be. Tibbets and Lewis relaxed a little in their seats as the Enola Gay quickly headed back out to sea. The main subject of conversation as they flew back home was the end of the war with Japan. How could they withstand such a weapon? They could not visualize the destruction they had left in their wake.

Aboard the Necessary Evil, Russell Gackenbach felt the atmosphere in the cockpit was unusual: “Normally, as you dropped your bombs, you’re heading home, you’re happy. You’re okay. You’re cracking jokes in a hilarious mood. This mission, we did not have that. It was quiet, subdued, awesome. We didn’t realize what it was, and by the time we got the fifteen miles from where the bomb had been released to where it exploded, the cloud was already higher than we were. We could see the cloud a hundred miles away. Especially the tail gunner.”

For Tibbets, the sight before him as he had circled the Enola Gay to get a good view of the target before they departed to the southwest would remain with him for the rest of his life: “The giant purple mushroom, which [Caron] had described, had already risen to a height of 45,000 feet. Three miles above our own altitude and was still boiling upward like something terribly alive. It was a frightening sight, and even though we were several miles away, it gave the appearance of something that was about to engulf us. If Dante had been with us in the plane, he would have been terrified!”

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Hiroshima Men: The Quest to Build the Atomic Bomb, and the Fateful Decision to Use It by Iain MacGregor. Copyright © 2025 by Iain MacGregor. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

Iain MacGregor

Iain MacGregor is the author of the acclaimed history of Cold War Berlin: Checkpoint Charlie and the award-winning The Lighthouse of Stalingrad: The Hidden Truth Behind WWII’s Greatest Battle. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, has spoken at many literary festivals and conferences in the UK and abroad, appeared on podcasts such as The Rest Is History and on television documentaries. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Spectator, BBC History Magazine, and The Guardian. He lives in London.