Inside the Creation of a Girl Scout Troop Unlike Any Other

Meet the Young Women Who Made it Happen

It was the one-month anniversary of the first gathering of the troop, before it was even a real troop, before it even had a name. Now the troop was off and running fast, and Jimmy was there to make it official. March was also Women’s History Month, so he decided to mark the occasion by recognizing local women in politics. Heidi Schmidt came with a woman she’d invited from the Queens borough president’s office and one from the local community board, so the girls could see women in positions of power. They discussed a wide range of topics, from racism to crime to gender equity.

A sense of quiet satisfaction bubbled up in Giselle as she leaned against the back wall of the room. This was what she had wanted for her daughters and the other girls living here—a chance to think differently about the world and their places in it. She looked over at Cori, who was listening so intently to the conversation, and said a silent prayer of thanks for everything and for everyone in the room.

Sanaa studied Jimmy. She listened as he said things like “Women can do anything” and “You can run for office” and “A woman can be president.”

Sanaa raised her hand. “Then what about that woman who tried to be president and didn’t become one?”

Though Sanaa’s survival tactic was to be the smartest, most personable person in the room, her tongue sometimes lay too heavy in her mouth, threatening to jumble her words, to make her a mumbler, so she worked to enunciate every word with authority, even if she was unsure of its meaning, even if she was uncertain of the pronunciation. As a result, her question to Jimmy came out as less of a query and more like a declaration with just a smidge of sarcasm.

Giselle shook her head, a little embarrassed yet impressed. Cori laughed. Heidi was in awe. At nine years old and in the fourth grade, Sanaa could not remember Hillary Clinton’s name. But she was well aware that there had been an election and that a woman had narrowly lost. Sanaa was smart enough to know that she had commanded the room.

Sanaa—full name Sanaa Nina Simone Angevin—was raised that way.

Her mother, Mickyle—who had grown up in Brooklyn and had fond memories of being a Girl Scout—had pushed her to master the alphabet and her numbers at an early age, playing Baby Mozart as Sanaa lay in her crib. Sanaa had been plucked for gifted and talented programs, stayed firmly on the honor roll, and strove to be the teacher’s pet. Her discipline and amiability had helped her as she bounced from school to school as her mother moved her and her brothers from Atlanta to New York, back to Atlanta, then back to New York again.

Sanaa was the embodiment of the person Mickyle hoped she would have been if there had not been obstacles in her way, if she had only made good enough grades to get a scholarship to a reputable college, if she had only not gotten pregnant before she had planned.

Troop 6000 was not an ordinary troop. It had hurdles to overcome that other new troops did not face.

By the time Sanaa was two years old, Mickyle was pregnant with her son Makhi and living in a shelter in Harlem. She moved to Atlanta, entering Georgia State University, juggling multiple jobs, hoping to make a little more money, trying to earn a bachelor’s degree that kept eluding her as her family grew; her third child, Malaki, was born when Sanaa was five. Mickyle thought she was finally making it in 2016 when she began looking for a house to rent.

But then Mickyle was in a car accident. The driver did not have insurance. Mickyle’s rental car money was running out and there was no public transportation to get her to the distribution center where she worked packing baby clothing; getting to her other job at a nursing home would also be a challenge using mass transit. With pressure mounting and time becoming a disappearing commodity, she began to fail her online college courses.

She decided to return to New York but didn’t want to impose on her mother or other relatives by taking up more space in already cramped, overcrowded apartments. Mickyle drove her rental car from Atlanta to Staten Island and ended up at PATH in September 2016. The family of four was placed at the Sleep Inn a month after Giselle and her family had arrived.

Sanaa wasn’t quite old enough to understand what was happening. They were in a hotel room with no stove, no privacy, no closet space. Mickyle told her children that their new surroundings and circumstances were not excuses to fail; they would have to step up. She used writing as a disciplinary tool. Every time her children misbehaved, did not complete chores, forgot to do homework, or were mean to one another, she made them write letters of apology. Sanaa hated composing those letters at first but soon learned that atonement expressed in writing went a long way.

Along with many other children of elementary school age at the Sleep Inn, Sanaa attended P.S. 111. The school did its best for an increasingly transient student population that carried fragmented academic records and a defensiveness that could pop up at any time on the playground or in the classroom. About one out of every ten students was proficient in math and English. In New York City school rankings, P.S. 111 hovered at the bottom; in its number of homeless students, it was quickly rising to the top. Because Sanaa’s defense mode was affability and achievement, she was immediately propped up as a role model for other students.

What the school could not accomplish in test scores it made up for in heart and activities, like the step team, the choir, and the library club. But Sanaa and other students who lived at the Sleep Inn yearned for something more. Once they walked home from school, they were required to go straight to their rooms, coming out only to warm up food in the lobby’s microwave. Sanaa had no idea that many of her classmates were living practically alongside her in the very same hotel. After all, there were almost no opportunities to interact: They weren’t allowed to play in the hallways; they couldn’t play unsupervised outside; they couldn’t visit or have sleepovers in one another’s rooms. Mickyle felt her children’s isolation every time they sat on their beds to finish up homework.

Then she saw one of Giselle’s flyers hanging by the elevator.

“Well, Sanaa, do you want to do Girl Scouts? I was a Girl Scout.”

Sanaa wasn’t sure what being a Girl Scout meant. When Mickyle explained to her that there were badges and patches to be earned, she couldn’t wait to get to the meetings.

Now Sanaa had a new goal. Her inquisitive eyes darted from one patch to the next on Hailey’s vest. What a rainbow of accomplishments! They proved that Hailey was not only a Scout but a good one. That’s what she would become, Sanaa decided: a good Scout. Hailey’s patches covered her entire vest, evincing her worldliness. Sanaa focused on Hailey’s favorite, a deep-blue oval at the top of her right shoulder that depicted Juliette Gordon Low’s house in Savannah, which was in Georgia, just like Atlanta, where Sanaa had come from. Many of the patches were “fun patches” that were collected but not necessarily earned. The fun patches came in all shapes and sizes—rectangles, squares, big circles, small circles, a pentagon, a triangle—and commemorated participation in Urban Day Camp, sleepovers, camping, and caroling, and recognized Hailey’s punctuality and her love of fashion. Of course, she had badges and special pins for selling cookies with the Sunnyside & Woodside troop.

After the meeting with Jimmy, all the Scouts lined up so that Jimmy and Meridith could pin them with the First Aid Badges that they had earned at the previous meeting, the one where Cori had taught them how to call 911. So now Sanaa had her first badge, and it was a merit badge—something she’d had to earn—rather than a fun patch; she only had a gazillion more to go to catch up to Hailey.

The Scouts all gathered around Jimmy in the dining area. Kiara’s father, David, who had shown up at the end of the meeting, asked them to pose. A green ribbon was placed across the door of the breakfast room, along with a troop 6000 sign.

Sanaa placed her hand atop Jimmy’s. Kiara, who’d been so sullen when she showed up at the second meeting, reached over behind Sanaa to put her hand in, as did Brithani and the other Scouts. Jimmy cut the ribbon with a pair of oversize scissors. Cori and Giselle laughed and clapped on the sidelines. David took more pictures.

Amid all the cheering, Giselle started to cry. She was overcome by a strange mix of emotions swirling inside her. Yes, she had accomplished something pretty damn impressive, but would she be able to maintain it? Troop 6000 may have grown a little each week, but the growth was incremental in a completely unpredictable way, because each week at least one or two girls who’d been there before failed to show up. A couple of them disappeared because their families had found housing and they’d moved out of the hotel, like other girls would be doing in the coming weeks and months. That was a good thing, but it was a reminder that Troop 6000 was not an ordinary troop. It had hurdles to overcome that other new troops did not face: What was good news for those in the Sleep Inn who’d now found homes was bad news for the nascent Girl Scout troop.

Amid the hugs and pinning, Giselle spotted Genesis lingering in the hallway next to the elevators waiting to pick up her sister Brithani from the meeting. At fifteen, Genesis was a little taller than Giselle, but she often dropped her head so that she looked shorter. She had a brown spot on the white of her left eye, more of a distinguishing mark than a blemish, enhancing her beauty. Whenever Genesis laughed, it was almost as if she did not think she should be laughing; she would stop herself and close her mouth as if holding a secret. She looked down at the hallway floor when she locked eyes with Giselle, smiling and then pressing her lips closed.

Recruiting older girls had proved just as difficult as finding parent volunteers. To begin with, they seemed to view the Girl Scouts just as Giselle had as a teenager—an activity that was a little corny, one for people with means and luxurious amounts of time to kill. And they had other obligations, adult obligations. They were responsible for younger siblings, getting themselves to and from school, helping with shopping or surreptitious cooking or laundry, all while trying not to be another burden on their parents. A study by the Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness found that in 2017 nearly half of all high school students experiencing homelessness said they were depressed compared to about 30 percent of students who had homes.

Genesis’s biggest worry was finding a job for herself. It didn’t matter what kind of work, all she cared about was the income she could earn. Her mother sometimes seemed paralyzed by the undertaking of caring for her family, and so her oldest daughter was in a constant state of uncertainty—about money, about her growing responsibilities, about whether the family would be able to stay in the United States. Genesis had come to the United States from Honduras later than the rest of her family. When she arrived in Miami in 2014, she was excited to join her parents and her two younger sisters, Brithani and Gianna. But she learned her parents’ marriage had soured, and Genesis was unexpectedly caught in the middle, struggling to learn more English while taking on the care of her younger sisters. After they lost their belongings in a fire in Miami, family in New York encouraged a move to the city, but they ended up at PATH, like so many other families.

Genesis hated the word immigrant—to her, it was code for un-American. “I have my papers,” she would say whenever anyone used the word to refer to her. Genesis only knew that she wanted to stay in the United States, she wanted to be a model, and she wanted to go to college. As a high school sophomore, though, she had never heard of the SAT even as she walked past a standardized testing prep program on the way from the subway to the Sleep Inn.

She could only focus on the basics: family, high school, and money. The other stuff would come once she took care of those three things. Her mother had named her from the Bible—Genesis, the beginning—but Genesis had no idea how to get to the end, to get to where she wanted to go.

Her school, Long Island City High School, enrolled about 2,500 students, mostly first-generation immigrants just like Genesis. It had a robust ROTC program and a culinary arts program with state-of-the-art equipment. The school was praised for turning around students’ lives, boasting a list of success stories who had won scholarships or made it into elite colleges. But about 40 percent of students never graduated. For all of the students who left and attained the impossible, there were a significant number who did not and never would. About 250 children per class would not get a diploma, and Genesis feared she would be one of them. Homeless students scored worse on proficiency exams, studies showed, and were more prone to absenteeism than housed students. Their lag was a reflection of a deeply segregated school system.

“Once you’re a Girl Scout, you’re always a Girl Scout,” Giselle said.

Genesis faced classism and racism. How she talked, how she looked in her cheap clothes, and her dark skin all made Genesis feel inadequate. People were confused when she spoke Spanish-accented English, not realizing that there were black Hondurans, too ignorant to make the distinction between an ethnicity like Hispanic and a race. It took Genesis a little longer than native English speakers to learn to read and write in her new environment.

Now she stood by the elevator on the day of the ribbon cutting. Giselle saw her and headed toward her.

“Hi,” Giselle said, embracing her. Genesis even had her vest in her hand. “Why weren’t you at the meeting?”

Genesis didn’t answer at first. She looked apologetic, or maybe disappointed. “I’m sorry. I don’t want to do this,” she finally said, handing over her khaki vest. She hadn’t even gotten it pinned with the First Aid Badge.

“Once you’re a Girl Scout, you’re always a Girl Scout,” Giselle said, forcing a smile through her dismay.

Then she took Genesis’s vest, holding it with the same care that she used when dressing a newborn to leave the hospital.

“You know what I’m going to do? I’m going to hold on to your vest.”

Genesis nodded, and Giselle saw tears in her eyes before the teenager turned away.

__________________________________

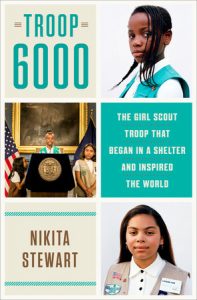

Excerpt from Troop 6000 by Nikita Stewart, copyright © 2020 by Nikita Stewart. Published by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Nikita Stewart

Nikita Stewart, author of Troop 6000, is a reporter covering social services for The New York Times. The Newswomen’s Club of New York recognized Stewart in 2018 for her coverage of homelessness, mental health, and poverty. She has been a finalist for the Livingston Award and the Investigative Reporters and Editors Award. She joined The New York Times in 2014 after working at The Washington Post.