Inside the Career of Tuesday Weld, a Hollywood “Poet of Failure”

Matthew Specktor on the Woman Behind the Movie Star

When Tuesday Weld appeared on The Dick Cavett Show in 1971, she was 28 years old. The age of a youthful actress in her prime, in other words, and yet the question had already been following her around for more than a decade. Why isn’t Tuesday Weld a huge star? It’s a question that still gets asked, perhaps, of this or that performer, who might be big, sure, or promising, but why aren’t they bigger still? Sometimes the answer is a matter of audiences and their taste, but other times, well, the question is a little more complicated.

The movie she appeared on the Cavett Show to promote—Henry Jaglom’s A Safe Place, co-starring Jack Nicholson and Orson Welles—could politely be described as “chaotic,” perhaps, but nevertheless. Nicholson himself had recently emerged as a huge star on the heels of the previous year’s Five Easy Pieces, and you could imagine—given the temper of the times in Hollywood especially, the mood that had emerged after the success of 1969’s Easy Rider, which allowed filmmakers to experiment more—that this film could have been expected to break her to a wider audience. Perhaps even she expected as much. Then again, perhaps not. As she sauntered out of the wings and onto the Cavett Show stage, Weld was freshly sober (though she was careful not to define herself as alcoholic; “I could have been,” she said when Cavett asked if she had ever identified as such, “but I stopped”).

If you watch the clip on YouTube today you can see it: Weld is cool as a matador when invited to perform the crooked dance of publicity. Strolling out onto the stage in big tinted sunglasses and a blue peasant blouse, a long floral skirt and a shoulder bag big enough to hold a week’s worth of groceries, she is at once guarded and open, defended without ever quite being defensive. She had been prominent in the American imagination since the beginning of the 1960s, but that prominence had defined her, perhaps forever, as a delinquent teenager. If the game of publicity involves being both naked and invulnerable—the “game” at least as defined by those who get to set the rules, the spectators—then Weld seems to be playing it perfectly. If it involves, rather, feeling like a human being instead of a fatted calf, well, then, who knows, but it’s worth noting that Weld retains her poise, and more importantly her sharpness, all the way through the interview.

When the next guest, Milton Berle, arrives and begins to bloviate confidently, and perhaps a little tiresomely, with all the entitlement of a male celebrity who’s used to being listened to, Weld interrupts him with an observation that seems telling. They are talking about Orson Welles, the question of whether the great director really enjoyed acting, or if he was merely slumming. Berle opines, naturally, that Welles must have enjoyed it, but Weld demurs. “I think he doesn’t even like himself for liking to act,” she says. Maybe he can’t help but be sucked into it a little bit, she adds, but “I just have a feeling he has that little argument with himself. I’ve never met an actor—an older actor—who was happy with himself, and his life.”

She says these words with a bright smile, as if she is just making an observation, but of course she would have been speaking from experience. There is that soft odor of self-loathing that so often trails the perfume of charm. That “little argument” would have been ongoing for her, as it is with me too. A director assembles films. A writer composes them. But an actor, whose whole life can feel like an exercise in impostor syndrome—there is the exhaustion of suspecting that you might be a fraud, which any creative person feels, and then there is the need to enact a performance of authenticity with your entire body before you can even let this possibility have its due—knows this quarrel, I would imagine, better than anyone.

*

Weld’s first real leading role came in 1966’s Lord Love a Duck. Which came after she’d been working for more than a decade, after she’d been catapulted to a certain sort of stardom by her one-season turn as Thalia Menninger, the money-hungry temptress on the wildly popular television show The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, and had come, thus, to occupy her position as America’s reckless young sweetheart. Lord Love a Duck is, it must be said, an exceptionally strange movie, one that anticipates by a good 20 years such pitch-black Gen X excursions as Heathers, but Weld lights up the screen from go in the service of a part that—not for the last time—addresses themes that would have been significant to her: Svengali-ism, fame and ambition, image manipulation and control.

The story of an emotionally disturbed high school student named Alan “Mollymauk” Musgrave (played by Roddy McDowall) and his friendship with a striving female classmate (Weld), the film is at once a lighthearted parody of American International Pictures’ Frankie-and-Annette-starring teen movies—Beach Blanket Bingo, Bikini Beach, etc.—and a deranged Faust narrative that takes clear-eyed aim at consumer culture. At one point Weld’s character, seeking entrée to a clique of popular girls known as “The Cashmere Sweater Club,” persuades her estranged father to take her shopping. The scene that ensues is, to put it bluntly, nuts, a consumer fantasia in which Weld whips herself into a sexualized frenzy by trying on a series of brightly colored sweaters. As she writhes and squeals in various shades of angora (“Pink put-on . . . papaya surprise . . . periwinkle pussycat!”), her “father” leers and trembles, rooting her on until he is positively bug-eyed with lust. It’s disturbing, upsetting—as lurid as anything in the Kubrick rendition of Lolita—but the scene travels so far over the top it hits like nitrous oxide: discomfort slides into shock and then straight-up hilarity.

The movie might not know quite what it wants to be (by the time Weld’s character gets married and then attempts, at Mollymauk’s instigation, to off her dim-bulb husband, we’ve left both realism and the zany, Hard Day’s Night–style poptimism of the film’s opening far behind), but it’s exhilaratingly perverse. And frame for frame, Weld’s performance is magnetic: no matter how weird things get, or how tonally confused the film becomes, you can hardly take your eyes off her. The same can be said of 1968’s Pretty Poison, which many consider to be the actress’s best—and certainly her most representative—film. Weld herself claimed to dislike the movie—she’d clashed with director Noel Black, and as she later told Cavett, she was incapable of enjoying a film she hadn’t found pleasure in making.

The lesson of loving a movie star isn’t that they are exceptional, but rather that they are ordinary.

If anything, Pretty Poison is even more messed up than Lord Love a Duck. Anthony Perkins plays a paroled arsonist who moves to an industrial New England town and soon gets mixed up with Weld’s wholesome-seeming high school girl. Thematically, the setup is practically identical to Lord Love a Duck, with the film playing on an association with Perkins’s role in Psycho, only this time . . . it’s Weld’s character who turns out to be the malignant sociopath, more deviant by far than her opponent. She’s not only immune to the hapless arsonist’s manipulations, she’s several steps ahead of him the whole while. It’s a strong performance, as Pauline Kael was the first to note, but it’s also one that imbalances the film that surrounds it a bit. Weld is so radiant—it’s hard to imagine a sunnier presence onscreen than she was at this juncture, and the movie maximizes this by kitting her out in majorette gear the first time we see her, turning her into an emblem of American wholesomeness—where the film itself is melodramatic and downbeat. In its way it resembles the Perrys’ adaptation of The Swimmer, training its queasy, psychedelic-era lens on the decidedly pre-psychedelic world of rural/suburban New England, without quite deciding which side of the divide it belongs to.

In a way, the very ambiguity of these movies, their ambivalent split between a mainstream cheer and a subversive violence, mirrors Weld’s own position: too sunny for the burgeoning counterculture, I suspect, and too sour for the suburbs. Yet there is such delight in them. A near-total absence of vanity, and a superabundance of joy.

*

Recently, I had lunch with a friend, an actress whose career has been rather more successful than Weld’s. We sat in the windowless gloom of an Italian restaurant near one of the studio lots, a place we both like because it is echoic of the older LA, in which she and I grew up—and because it is largely empty most of the time: there are few other diners, and not many people likely to bother my friend who, I would suppose, is used to fending off paparazzi and autograph seekers anyway. We talked, as we always do on those infrequent occasions we see one another, about writers and books, films and Los Angeles—anything except “the biz,” which she seems to dislike as much as I do—and at a certain point she let slip a comment that surprised me.

“I wish I had worked more,” she said. “When I was younger, I turned down so many things.”

“Did you?”

I sipped my glass of midday chianti. I suppose I was startled to hear this note of regret creep in. I’d thought my friend had done pretty much exactly what she wanted, which was pretty much exactly what anyone would have wanted. Her filmography was stellar, filled with nominations and awards, to say nothing of performances any actress would be proud to have given. What hadn’t she done? I wondered. I studied her face, its pensiveness: the subtle workings of all those nerves and muscles—she surely didn’t even know she was doing it—creating shades of meaning and emotion I could myself scarcely name, even at rest. It was a face I’d watched for decades, playing guileless high school students and drug-ravaged criminals, wisecracking molls and tormented theater actresses. Now it was deep in the role of her own private self.

“I turned down _____,” she said, naming a movie that had won multiple Oscars, not least for its now-iconic performance by its female lead, as a sleep-haunted detective. “I just couldn’t get my head around the script.”

“Wow.”

“I turned down a whole bunch of things,” she said, then rattled off a slew of titles—Pretty Woman was one; Thelma and Louise, another—that suggested an alternate history, not just for her but for the last 30-odd years of Hollywood. I saw this history pass before my eyes—her star glowing differently, other careers diminished or eradicated, or enhanced by different roles they had taken instead—as I swapped her into one film and then the next. There was the disorienting question of whether the pictures themselves would have been better, or worse, if she’d appeared in them; if even a superior performance could have led somehow to an inferior movie.

“Do you regret it?” I said.

“No.” Her eyes narrowed. (I regretted it. I would’ve enjoyed seeing her in those roles.) “I just wish I had taken on more. I don’t regret the things I did, or the things I turned down. But I feel like I missed something.”

Surely, we all feel this, eventually. Surely, we all feel the negative weight of lives unlived, alternate paths not taken. But given a choice between a stardom she didn’t seem to want and an ordinary obscurity she didn’t seem to want either, did Weld ever regret any of her choices either? After all, she’d famously turned down parts—in Bonnie and Clyde and in Lolita, in Cactus Flower and in Rosemary’s Baby—that had launched other actresses to stardom, and films (like 1969’s Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice) that had achieved enormous popular success. So did any of this bother her? Or was this, too—her public role as cult icon, the semi-popular figure she had become and in fact would forever remain—just another part for her, the actress? The one, indeed, she may have been born to play.

*

Of course, there is more to life, and to Los Angeles, than stardom. In his excellent monograph Hadley Lee Lightcap, the writer Sam Sweet describes this city—the one where young people, creative people, arrive every day still to chase their celluloid dreams—in terms that are a little contrary to everything we’ve ever allowed ourselves to imagine of this place. “The eternal Los Angeles is composed of infinite intersections full of nothing remarkable,” Sweet writes. “Each one offers a similar but always slightly different combination of peeling signage, concrete pathways, and buildings painted and repainted in so many layers of nameless color that it’s no longer possible to tell whether they’re new or very old. These places don’t ask to be discovered and are rarely remembered. Here the city is so devoid of historic significance and attraction that you wouldn’t know its tempo unless you deliberately attuned yourself to it.”

The movies barely deserved her. She could make even the technology that created her, somehow, seem common.

This is the Los Angeles I live in now, and it’s the one you do too: the one that surrounds, and permeates, the world of the studios and the faded stars, and the elevated mansions of the living ones too. Sometimes, late at night, I go out and drive around its silent avenues, peering up at that vague moon that hangs above its streetlamps, palms and jacarandas. Some nights I stay in instead and dream, a little feverishly, of Tuesday Weld squinting at bootleg DVDs and grainy YouTube streams into the small hours. When the career of a public figure fails to live up to our ridiculously inflated hopes for it, we call that a tragedy, or at least a shame. When a middle-aged civilian, fails to live up to his inflated hopes for himself, that’s no tragedy, it’s adulthood, an education that arrives better late than never. The lesson of loving a movie star isn’t that they are exceptional, but rather that they are ordinary. That they, and you too, are subject to the same laws of gravity that govern everybody else.

*

After Pretty Poison flopped, Weld’s career still seemed to stretch out brightly in front of her. A 13-year industry veteran, she was, incredibly, still just 25 years old. It felt like she’d been doing this forever. Even as the tastemakers, like Kael, stood up for her, and she nabbed a runner-up for 1968’s Best Actress from the New York Film Critics Circle, she was stuck pushing up the Sisyphean hill of her sex bomb reputation. If people had only been able to see the film—it was in and out of theaters overnight, as the producers couldn’t find a distributor—it would’ve been a hit. Or maybe the cult of Tuesday Weld is its own self-perpetuating machine at this point, doomed to overrate her performances in movies that don’t quite come off. Maybe the movies aren’t that good, maybe I, now a card-carrying cultist, myself, overrate them, and this effort to resurrect an actress who is still very much alive is just a fool’s errand.

But her later performances—in films like 1981’s Thief and 1978’s Who’ll Stop the Rain, or in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America, which is best seen in its 1984 international version, rather than in the bowdlerized one that was released in the US—all suggest Weld as a poet of failure, someone who was inexorably drawn to parts that showcased deterioration and disappointment, unhappiness and collapse. And whether one watches her in a great movie (like Once Upon a Time in America) or a lousy one (like 1971’s A Safe Place, Henry Jaglom’s “experimental” dreck-fest that wastes her along with Jack Nicholson and Orson Welles), a functional one (say, 1970’s I Walk the Line, which casts her oddly opposite a sluggish Gregory Peck) or a good one (1965’s The Cincinnati Kid) in which she’s just not given enough to do, the effect is the same: like seeing a figure that could as easily be spun from liquid gold and moonlight—a goddess of stardust and cream—seem persuasively, ineffably natural on camera. The problem was never that Weld “didn’t get the parts she deserved,” nor even that she turned so many of them down. The problem was that the movies barely deserved her. She could make even the technology that created her, somehow, seem common.

*

For the most part, I am uninterested in Weld’s personal life, in combing its contours—three marriages (the latter two to actor Dudley Moore, from 1975 to 1980, and to the concert violinist Pinchas Zukerman, from 1985 to 1998) and two children—for clues. For the most part, the information isn’t available anyway, but there is one moment that intrigues me. It came just after her first marriage, to a screenwriter named Claude Harz, had fallen apart. In 1970, Weld and her infant daughter decamped to London. She seems to have split from her husband amicably, at least as these things go. She waived alimony, telling the New York Times, “I don’t see any reason for Claude to have that hanging over his head. . . . If he has the money, I’m sure he’ll give it to me.”

Then she fell into a period of drift, of windblown wanderlust that may have been—if you’ve ever had this feeling, you know—a form of clinical depression. Or maybe she had always been this way, her life in chaos even when she was a small child, moving from coast to coast and school to school as Yosene jerked her around and forced her to go to work as a toddler. “I feel so misplaced everywhere,” she told the Times, on the eve of yet another departure, getting ready to set out now from London to Paris. “Sometimes I just walk the streets at night, for hours and hours. I’m incredibly restless.” Her restlessness came to an end only when, while she was home for a while in Los Angeles, her car broke down—a beloved Porsche roadster she’d purchased at Elvis’s recommendation when they were shooting 1961’s Wild in the Country—and then one night, when she was visiting Catalina Island alone, her house caught fire.

Racing home to Malibu, Weld found herself stuck on the ferry for several hours. Santa Ana winds had knocked down the telephone wires, and the actress had no idea where her daughter was. She arrived the next morning to find her child safe—she’d been spirited from the blaze by her nanny—but everything she owned, everything, had been burned to ash: her furniture, her journals, those years of writing she’d been saving for an eventual memoir, the paintings she’d done, her memorabilia, her clothing: all of it was gone.

What did it feel like? I wonder. Having lost all of her possessions, whatever spoils she’d amassed, did the actress feel disconsolate? Or did she—picking through the wreckage with the cold surf pounding behind her—did she, rather, feel free? “I went to look at the ashes, but I didn’t cry,” she told an interviewer. “Aside from [my journals], none of it mattered.” Later, she said, “I’m suspended, floating. I’m not happy, and I’m not sad.” Profiles from that year, 1971, describe her nomadic lifestyle. A Rex Reed piece, written while the actress was doing publicity for A Safe Place, invokes the chaos of her New York City hotel room, its door propped open with a cardboard box, the floor strewn with “notebooks crammed with jottings in soft lead pencil . . . a portable radio, vitamin pills, bottled water, ashtrays filled with unsmoked cigarettes,” Weld herself presiding in a ratty red sweatshirt stamped with the Superman logo. Like she had nothing and wanted nothing and maybe, just maybe, actually preferred it that way.

__________________________________

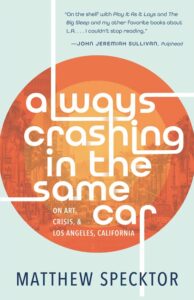

Adapted from Always Crashing in the Same Car: On Art, Crisis, and Los Angeles, California by Matthew Specktor. Published by permission of Tin House. Copyright (c) 2021 Matthew Specktor.

Matthew Specktor

Matthew Specktor is the author of the novels American Dream Machine and That Summertime Sound, and the nonfiction books The Sting and Always Crashing in the Same Car. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Paris Review, The Believer, Tin House, Vogue, GQ, Black Clock, and Open City. He has been a MacDowell Fellow and is a founding editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books. He resides in Los Angeles.