for Never Angel North

Because I hated him, Mom spent the ride to Chad’s house talking about Presque Isle. How lucky we would be to be so close to the state park. How fun it would be for me and her and Billy to go to the beach, ride bikes, take walks. We didn’t even have bikes. We hadn’t even had to rent a U-Haul to fit all our stuff into. None of it was worth taking, and Chad had promised her all sorts of things. She left so much behind, in a pile in the living room, knowing that the landlord would rather her be gone than the place be clean when she left, even. We had to leave. We had to get out before the eviction notice came to full term and followed her forever so she wouldn’t even be able to rent something as bad as our old place had been. Not being barred from things was our only safety net, and she clung to it. Chad came along at the right time. With the right words. And he could even tolerate me, maybe.

But I couldn’t tolerate him. And the truth was, he had so many questions about me, about why my mother had allowed me to do what I’d done, why I was living the way I was living, how she could support it. I turned to the back where Billy was in his car seat, drooling a little on himself as he ate a lollipop. Mom had hit her credit limit on her last card buying it, a loaf of white bread, a jar of peanut butter, and a tank of gas for the trip to Chad’s house. Billy let his big sister wipe away the sticky spit from his chin, tell him lovingly how gross he is. He was only five, had only ever known me as his big sister. It’d been so easy with him. Easier than it was with Mom, even, who didn’t understand but had a big enough heart to, eventually. I didn’t think Chad’s heart was big. I knew it wasn’t. It had maybe enough room for Mom, maybe, and Billy—he was just a little boy, who couldn’t love him? I was going to be the problem in the situation. I always am.

We’d lived on the lake, in a summer town. Nobody stayed past when the first blush of autumn hit the tree leaves. We’d always stayed. My mom had bartended in the summer, making the money that sometimes carried us through the winter, when she didn’t drink it all away at the only place that stayed open for the locals. When she did, she picked up cleaning jobs in the winter. Back years ago, when my dad was still around, I used to break into the summer places with my friends. We didn’t steal anything, we didn’t break anything, we weren’t those kinds of kids, the kind who just wanted to fuck with the summer people. We would break in in the winter and just hang out, sometimes smoking weed we’d stolen from our parents, even though we were only twelve or so at the time. My hair was short back then, I wore baggy boy’s clothes, nobody knew, even I didn’t let myself know. We used to sit in these big plush chairs, pretend the place was ours. After a while, after we got stoned or drank the beers some older kid had bought us, we’d just sit there, talking, dreaming shit up. About how we’d buy one of these places one day, no more living in the uninsulated houses that the lake effect’s cold winds cut right through the walls of. When we left, we cleaned up after ourselves so no one would know we’d been there. That way, we could always go back.

My mom was still talking about Presque Isle, even though I wasn’t listening and she knew I wasn’t listening. Her face was drawn, it had gotten worse in the last few years. When I was younger, she had been beautiful, really stunning, with her long black hair and pale skin and bright green eyes. Her eyes had become bloodshot, and there were burst veins around her nose that you could see when she didn’t wear foundation, like she wasn’t then. The guys in the bar, they still got the best version of her, the one that wore the makeup and the clothes that hid her beer belly, the one who smelled like faint, summer perfume. I could see her disintegrating. I knew she thought Chad was her last hope, and that was why she was hanging on so tight, even though Chad didn’t understand how she could let me be the person I am.

“You won’t have to see him much, you know,” she said finally, agitated that I wasn’t paying her any attention. “He works so hard, such long hours. He isn’t around much, and when he is, he’ll mostly be with me.”

Chad’s the foreman of a local construction unit. We’d been to Chad’s house before; he and his friends built it themselves. It’s huge and the outer walls are lined with puzzle pieces of fieldstone. I saw my mom’s face light up the first time he had us over for dinner. It didn’t dim as Chad asked me questions that weren’t really questions but hate disguised as inquisitiveness. It had been five years since I started presenting the way I felt, and I’d gotten used to discerning the reality of such things. My mom, she still didn’t know.

“Well, it’s only two more years until I graduate,” I said. “I guess I can tolerate him that long.”

“Look, we’re going to have a great time out here, when I’m not working. You’ll see. You’ll want to go to the island every day.”

“It’s a peninsula,” I said quietly.

She stared straight ahead, as if she could already see Chad’s house and him in it, waiting for her. I spread peanut butter on a slice of bread, folded it in half, tore half off, and gave it to Billy. Then, eating the other sticky half myself, I signed on to Snapchat and began talking to my friends.

*

That night, after Chad had moved our clothes and the few other things we’d brought into the house, he and Mom got drunk in the kitchen while making dinner. Me and Billy sat playing Mario Kart Tour in the living room, on Chad’s big TV. Chad said he’d bought the game for us, but he was playing it when we got there. My mom’s face had lit up like she’d won the lottery when he said it, and she’d shot me a look behind her joy.

I could hear them dancing around and clinking glasses in there while old country music played on the kitchen speakers. Or something gravelly and slow. Promise you’ll find me, I want you to find me. Billy was happy, light splashing off the screen onto his little face. There was that, at least.

“Hey, come in, come in,” Mom yelled finally. The house smelled good, like onions and garlic and cream and butter. Mom’s a great cook, when she doesn’t pass out before dinner. I don’t blame her, really I don’t. She’s had it hard. After my dad died, there’s been a lot of things that I wouldn’t wish on anybody, most of all someone like her, who gives and gives to people until she’s got nothing left. But it attracts the wrong kind of people, always, all her selflessness. I’ve promised myself I’m never going to be like that.

Dinner was sitting out on plates when we got there, like we were some family in a sitcom. Me and Billy sat at the table, and Chad poured himself and Mom two more drinks, gin and tonic. Billy got juice and I drank water. I didn’t drink anymore, ever, not after watching Mom, and I don’t think Chad would’ve given me one anyway. They were still tipsy, walking around, grabbing forks and knives, and sharing a sloppy, drunken kiss by the sink. I turned away and looked out the window, toward the lake.

You can see the lake from Chad’s house, it’s right on the water. Mom told me once that, being a bachelor, not having a wife and kids, Chad had saved up a lot of his money so he could live the way he wanted to, make his house perfect. She’d told me that like a warning, almost. I got the subtext that I was not to fuck it up. I looked over the dark lake, a lake I’ve known all my life. It looked different from here than it did from our old summer town. As if it belonged just to the people who lived on it, while where we were from it looked as if it was for anybody. I hated this view.

Dinner tasted good, was okay, I guess. Chad kept trying to talk to me about the game that Billy and I had been playing, but I didn’t say much. I kept looking at my phone. I kept refreshing Instagram and going onto my Snapchat app. Mom hates that I talk to people on the internet more than I talk to her or anybody else I know. But, honestly, when you grow up somewhere like where I grew up, the internet is the only place you can find people like you. She thinks it’s all rapists and neo-Nazis, but if I didn’t have my other trans friends on the internet, I wouldn’t have anybody to talk to about things, ever.

I was talking to my friend Zoe, a trans woman who lives in San Francisco. I can’t wait until I have a life like hers. She’s older, twenty-two, and she looks out for me a lot. We were talking about how I could get estrogen, something we talked about all the time. She knew Mom wouldn’t let me go on puberty blockers, and there was no doctor around here that would prescribe them, anyway.

“Put the phone away, we’re having dinner,” Chad said, when he realized I wasn’t going to respond to him. I looked up at him. I’m not great at hiding what’s inside me, it always shows up on my face. I’ve always been that way. Before I came out, before I started to dress and act the way I wanted to, my mom always used to take my face in her hands and ask me what was wrong, why I looked so sad, what was inside my head. I could never tell her, not then. And when I finally did, she cried and cried for about a week before she pulled herself back together and said we were going to face everything together, and that was that.

“You can’t talk to me like I’m your kid,” I said finally.

My mom put her fork down. Actually, she dropped it, and it made a loud noise against her plate. “June,” she slurred at me.

“I’m not his daughter.”

Chad cocked his head at me and lowered the shelf of his heavy eyebrows as if I was an insolent employee on one of his construction sites. “Are you anybody’s?” he said, then, before Mom could realize, he added, “You don’t listen to your mother, that’s for sure.”

But I got it. I heard the subtext. I knew what he was saying. I left the room and went to lay down in the cot he’d set up for me in one of the guest rooms. It was just until he got us some beds, he’d said.

I went on one of my gaming sites. I played some old 8-bit games, just to fuck around, to not think the thoughts in my head. My avatar on the site is the best picture of me, from a straightforward angle, my blue eyes big and my face all cheekbones. I almost look exactly how I want in it. It wasn’t long before some older guy started talking to me, asking me to send him more pictures. In the dark of the room, I turned on my flash and took some more selfies at just the right angle and sent them his way.

“I’d like to take you away,” he typed at me. “Marry you.”

“I’m sixteen,” I wrote back. And then I signed off with a sigh.

*

Mom was up earlier than I expected her to be the next morning. I could hear and smell bacon popping and sizzling in the kitchen, all the way from the upstairs room I was in. Mom didn’t have a job yet, and I guess she wanted to make everyone as happy as she could until she got back behind a bar most of her nights again. She hadn’t cooked twice in a row for me and Billy in a while.

I went into the bathroom and shaved, then wandered downstairs in my pajama pants, expecting to see only her and Billy. It was early, around eight, but I knew that Chad got up before dawn for work. But there he was, sitting at the table, waiting to be served. I noticed the gray day outside on the lake. I guess his work had been rained out for the day.

“Hey, Junie,” my mom said, kissing me on the cheek as if the night before hadn’t happened. She was willing everything to be okay. That’s how she gets by, has gotten by for so long. No matter what happens to her, no matter what scumbag steals her tips after she let them into the house to drink or get high, no matter what guy slaps her, no matter what, my mom always tries to start a new day as if it’s brand new. I’ll never be like that, either.

“Morning, Mom,” I mumbled. “Chad.”

Billy was still sleeping, and my mom served us all breakfast without waking him up. “I’ll cook again for him later,” she said. That was something I hadn’t seen her do, maybe ever, cook a meal at two different times. I guess her honeymoon period with Chad was spilling over on everybody.

“Maybe we’ll go down to Presque Isle later if it clears up,” my mom chirped at me, as we sat poking over-medium eggs with bacon strips.

“Don’t want to go down there today,” Chad said. “Not with the storm.”

“But the rain’s gotten lighter than this morning,” my mom said. “It might clear by afternoon.”

“Storm days, there won’t be a lot of people there. Old legend. The Storm Hag.”

My ears perked up and I googled “Lake Erie Storm Hag.” I clicked on the images tab, and there she was, this fearsome creature with green skin, green hair, green teeth. Her eyes were without irises, black like a low storm. Jenny Greenteeth, they called her. They blamed her for the wrecks of ships, for calling sailor boys down to their watery deaths. Something vibrated in me.

Chad was still talking, but I didn’t hear him, glossed over his words in my head, searching out more of this Storm Hag. I came back to his words as he was saying to my mom, “Just a local legend. Like Bessie or those orange-eyed Bigfoots. Probably nothing. Still, you’ll find a lot fewer people on Presque today than you would with clear skies.”

“Good,” I said. “I hate people. Mom, let’s go later.”

Chad glared at me, as if I was defying him again, like I had last night with the phone. I guess I was testing him. I do push things sometimes. I could have just said nothing.

When my mom picked up the plates and was at the sink rinsing them off under the loud water, Chad got up to get more coffee. He stopped by where I was sitting and said, real low, “Watch your fucking mouth around me.”

I glared up at him and said, just as low, “My mother deserves better than you.”

He smirked. “She’s had worse.”

And it was true, I knew it was true, and he knew it was true. But somehow, I don’t think he meant the drinking buddies that came around only on payday, when the house was stocked with liquor, I don’t think he meant the guys who hit her, I don’t think he meant the stints in rehab when one of the boyfriends decided he wanted to spend her money on meth. I think he meant me. I think he meant the fights that happened at school, back when I first came out, my mom having to come in and try to explain things she didn’t even understand to people who understood even less. I think he meant the looks we’d get, walking around our summer town, when she would try to hold her head high and call me the name I’d chosen. I think he meant me, and all I’ve put her through. And I think what he meant was that no matter what a shit-ass he was, he was still better than all of it, and that’s all he ever had to be. Not good to her. Not good to me or Billy. Just not as bad.

“Fuck you, Chad,” I said, and walked out of the room.

As I went upstairs, I googled “Jenny Greenteeth” on my phone, and I found this song that she sings, like a siren, right before she pulls the men down. “Come into the water, love, / Dance beneath the waves, / Where dwell the bones of sailor lads / Inside my saffron caves.” I thought of how lonely the Storm Hag must be, underneath all that green water.

*

Later that day, Mom and Billy and I were standing on the shoreline, Mom with this dumb set of yellow binoculars that Chad had given her.

“It’s the best time for waterfowl migration,” she said. “We can see more birds here than we ever have in our lives, probably.”

Mom doesn’t know anything about birding. Chad must have told her, just like he gave her those dumb, glowing binoculars that Billy kept grabbing for. She would bend down and hold them up to his face, and then, after he looked and laughed, he would swat them away. She asked if I wanted to see. I said no. I didn’t know what different kinds of birds were, and neither did she.

I wandered down the beach by myself while she tried to show Billy seagulls and some other birds nobody knew the names of. I kicked the sand with my bare feet. I’d taken my Chuck Taylors off, even though it was April, even though the water had made the sand cold, and my feet were cold, too. The day was still gray, but she had been right: the rain had lessened.

I kept walking the beach, even though I could hear Mom calling for me to come back. I pretended the low waves from the earlier storm were too loud, that I couldn’t hear her. I kept thinking about the next two years stretching out in front of me like the long sand of the isle. I had kept my grades up in school. I’d already applied to college, as an early-decision candidate. I wrote sad essays about my hardships. I could make it until then, I kept telling myself, just like I was walking one foot in front of the other down this beach, until I got all the way to the end.

“Love,” I heard.

I snapped my head to the side, thinking my mom had come up behind me, run to catch me, whispered this soft word under her breath.

But she wasn’t there. No one was at the part of the beach I was except me and the birds, diving and swooping in the stormy sky in an untethered wind dance.

*

We’d been at Chad’s house eight days when he slapped my mother. I just sat there and watched. Billy started to cry. Chad stood back in the middle of the living room, where he’d done it, as if he was waiting for all of us to come together and attack him. None of us did anything. My mom sat down on the couch with her hand on her cheek, crying.

“Take Billy and put him to bed,” she said. So I did.

I tucked his blanket that he loves, the little fuzzy baby-blue one, right up under his chin while I kept saying, “It’ll be okay, it’ll be okay,” until he stopped crying.

“Why did he hit her?” he kept asking. “Why did Chad hurt Mommy?”

__________________________________

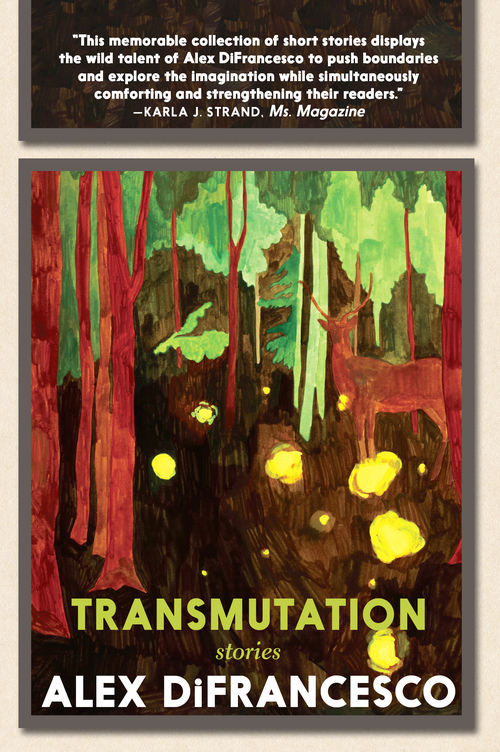

Excerpted from Transmutation: Stories by Alex DiFrancesco, with permission of Seven Stories Press.