Inside Edward Gorey’s Massachusetts Home

The Iconic Illustrator Was, Unsurprisingly, a Collector of Art

Edward Gorey loved collecting, which he preferred to call “accumulating.” To better understand the Gorey bequest and his motivation as a collector, it is helpful to observe how he lived with his collections. From flea market finds to fine art purchased from Manhattan dealers, he filled his New York City apartment and then his home on Cape Cod with his collections. Gorey’s relationship to these physical objects crossed into the emotional realm and is best understood in the context of the philosophy of the twentieth-century cultural critic Walter Benjamin. Benjamin observed the evolving relationship between one’s private living space and its contents. He claimed, “For the private individual the private environment represents the universe.” He further described the significance of interiors and their contents to the collector, who “dreams that he is not only in a distant or past world but also, at the same time, in a better one.” Benjamin’s philosophy is a logical jumping-off point for our interpretation of Gorey’s interiors as an extension of himself, and, conversely, of how these interior spaces were Gorey’s creative laboratories.

From 1953 to 1983, Gorey lived with as many as six cats in an apartment in Manhattan’s Murray Hill neighborhood. In 1978, photojournalist Harry Benson photographed Gorey in his apartment for a feature in People magazine. Benson’s portraits of Gorey are possibly the only surviving images that offer a glimpse of his collections at this address. In 1979, Gorey bought a 19th-century sea captain’s house on Cape Cod. He went on to accumulate art, objects, and a vast library of 26,000 volumes, creating what one journalist later described as “cloistered clutter.”

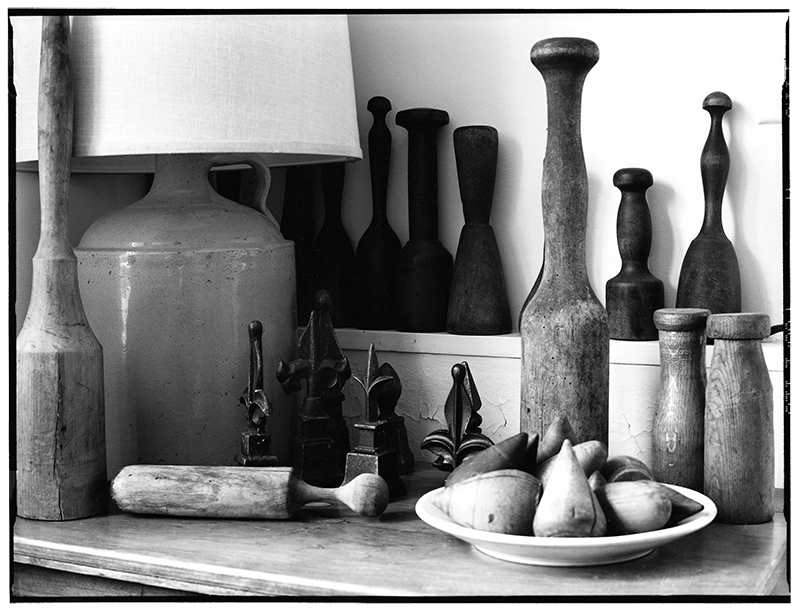

Kevin McDermott, Detail of Edward Gorey’s Living Room, from Elephant House, 2000. Collection of the artist.

Kevin McDermott, Detail of Edward Gorey’s Living Room, from Elephant House, 2000. Collection of the artist.

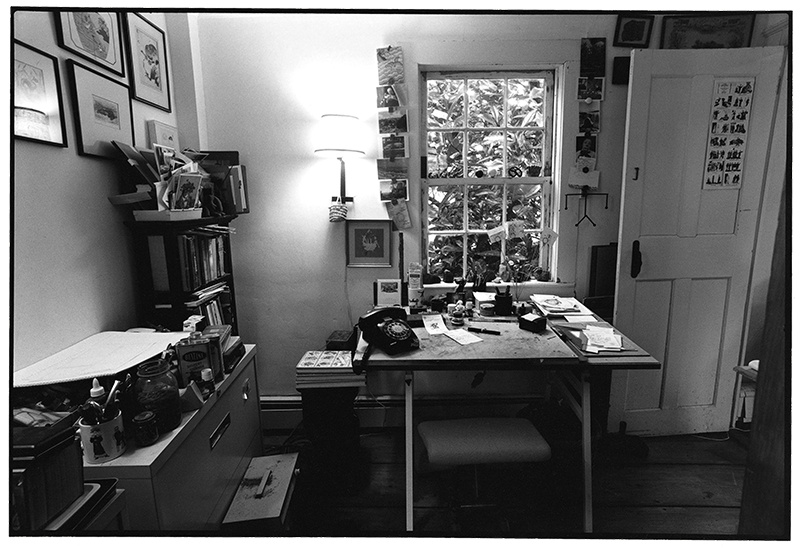

Kevin McDermott, The Studio, from Elephant House, 2000. Collection of the artist.

Kevin McDermott, The Studio, from Elephant House, 2000. Collection of the artist.

Number 8, Strawberry Lane, Yarmouth Port, now a designated historic property, is open to the public and has preserved a few of Gorey’s peculiar arrangements. The house during Gorey’s lifetime is far better documented than is his city apartment. The actor-photographer Kevin McDermott created a beautiful visual record of this sanctum. Published in 2003, Elephant House: or, The Home of Edward Gorey is not only a tribute to an artist McDermott deeply admired and respected; it also informs our understanding of Gorey’s obsession with physical objects, both natural and manmade, large and small. The photographs of Gorey’s second-floor studio reveal a tiny room no larger than a walk-in closet. When it came time to translate his conceptual ideas into artworks, Gorey crammed his six-foot-four-inch frame into this intimate space, since he admitted he “[didn’t] need much room” to do his drawings. To channel these imaginary worlds onto the page, Gorey plucked props, plots, and patterns from his vast mental inventory and from his accumulated objects.

*

Gorey’s earliest purchases were three drawings by Balthus. This purchase was likely spurred by new financial stability. Gorey typically published one book a year, beginning in 1953 with The Unstrung Harp, until 1963 when he published three major works including The Vinegar Works: Three Volumes of Moral Instruction, a suite of cautionary tales that included the now-iconic Gashlycrumb Tinies, the tragic alphabet of 26 children who die untimely deaths; The West Wing, a Zen-like series of textless illustrations of menacing objects and ominous rooms; and The Insect God, the story of a toddler sacrificed to insects. Gorey also published The Wuggly Ump, about a fantastic creature that devours small children.

Balthus, Étude de Personnages (Figure Studies), 1954. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Conn.

Balthus, Étude de Personnages (Figure Studies), 1954. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Conn. Bequest of Edward Gorey, 2001.13.20.

This success enabled him to buy “fine” art; in 1963 he bought three “minor but good” figure drawings by Balthus, one of his favorite artists. They marked his appreciation for Balthus’s larger body of work, which he knew firsthand from major exhibitions in New York. Gorey’s vast library included every monograph on the artist and the first comprehensive catalogue raisonné of Balthus’s work. Similar to Gorey’s own stories, Balthus’s pictures featured recurring motifs of cats and children as harbingers of strange, ominous acts. (A notable difference, though, was that while Gorey’s children might be threatening, they seemed virginal as contrasted with Balthus’s young girls in their explicit poses.) Both artists drew on the literary tradition of 19th-century illustrated cautionary tales of Heinrich Hoffmann such as Slovenly Peter (Der Struwwelpeter). In the 20th-century context, Gorey’s and Balthus’s works were often associated with surrealism and the prevailing interest in dreams.

Edward Gorey, “At the Villa Nemetia the sleepers / Are disturbed by a phantom in weepers; / It beats all night long / A dirge on a gong / As it staggers about in the creepers.” Illustration in The Listing Attic. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1953.

Edward Gorey, “At the Villa Nemetia the sleepers / Are disturbed by a phantom in weepers; / It beats all night long / A dirge on a gong / As it staggers about in the creepers.” Illustration in The Listing Attic. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1953.

Balthus was particularly interested in dreaming and made a series of paintings about dreaming figures. One of the drawings Gorey owned, Étude de Personnages, is a preparatory study for one of these pictures. The figures in the sketch closely resemble the two people in La Rêve II (1956– 57; Private Collection), where a standing female figure with flowing hair reaches toward a sleeping figure—also female—whose head is resting on the arm of a couch. In the drawing owned by Gorey, however, the sleeping figure appears to be male. His darkened eyes are in a trancelike state, and his body is slumped, passive. The figures’ bodies fade into the blank page, suggesting an apparition. Their haunted appearance brings to mind Gorey’s characters that are preoccupied by seen and unseen forces, such as the Throbblefoot Spectre in The Object-Lesson or the shadowy “phantom” in The Listing.

Gorey’s early work from the 1960s resonates with the moods, motives, and characters in Balthus’s paintings and drawings. There are notable affinities between two of his stories he wrote around the time he bought the Balthus drawings. In 1961, he published The Curious Sofa: A Pornographic Work and The Fatal Lozenge. In The Curious Sofa, sexual tension abounds in the form of innuendos and playful words, such as the naughty game of “Thumbfumble,” and references to objects placed in suggestive places.

__________________________________

From Gorey’s Worlds. Used with permission of Princeton University Press. Copyright 2018 by Erin Monroe.