Inky and Determined: In Praise of Writers Who Self-Publish

Lewis Buzbee on the Benefits of Taking Book Production Into Your Own Hands

“Type gives body and voice to silent thought. The speaking page carries it through the centuries.”

–Friedrich Schiller

*Article continues after advertisement

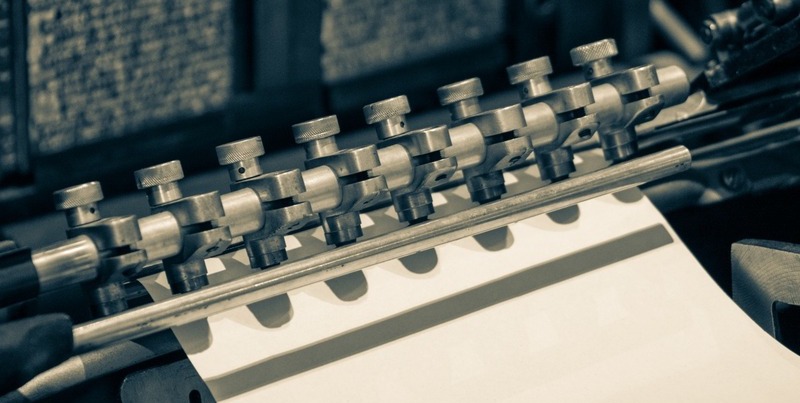

In the summer of 1917, in the dining room of the Woolf home, Hogarth House, Leonard and Virginia were getting ready to pull the first two pages of her story “The Mark on the Wall.” Her hands stained with ink, Virginia had spent long hours setting the Caslon Foundry type into composing sticks, one line of text per stick, the letters in reverse, of course. She finessed each line with kerning, blank pieces of type between words that properly space the line.

When the text filled the hand-press’s case, she leaded the spaces between the lines, to produce a welcoming page. Then she locked the case. Leonard inked the case and pulled the press’s handle; the platen and the paper rose up against the type, and the pages were machined. Virginia pulled off the fresh pages, which made a satisfying kiss as they separated from the case. There were her own words, written by her and now embodied in the world by her: “Perhaps it was the middle of January in the present year that I first looked up and saw the mark on the wall.”

Self-publishing… has always been a viable course for writers to achieve what they most want: To put their words before readers.

*

Only a few months earlier, the Woolfs had purchased a small printing press, including type and accessories, along with a 16-page instruction pamphlet. It all cost £19, which they could afford thanks to a tax refund. Both Leonard and Virginia thought that the “manual occupation” of printing might offer a change from their constant writing and reviewing; they would start their own publishing house, the Hogarth Press.

For their first publication they chose Two Stories, one by Leonard, “Three Jews,” and one by Virginia, “The Mark on the Wall.” By July 1917, the first edition of 134 was printed and bound. Virginia did the binding. As a teen, she had taught herself to bind books, a popular pastime then, re-covering whatever old volumes she could get her hands on. Two Stories is bound in a red-and-white-diamond design, one both busy and plain, on linen paper, with title and authors in black against it. The book was hand-sewn with red thread.

It took the Woolfs two and half months to produce the book. They advertised it by subscription, and it sold out within 3 months, netting what they considered an astonishing profit of £7.

Both writers had already published by this time. Leonard had several titles to his credit, and Virginia’s first novel, The Voyage Out, had appeared in 1915. It’s clear that, along with the idea printing might afford a comforting diversion, they also shared a sense that self-publishing would abet their writing. Virginia especially thought she could take her fiction in new directions, without the arbitrations of others. “I daresay one ought to invent a completely new form,” she wrote to David Garnett.

“The Mark on the Wall” does present this “new form,” the story of a woman who simply, and only, contemplates a mark on the wall near where she sits. Pondering this mark, the narrator inhabits the room and her thoughts with an onrush of images, from The Tube and Sunday lunches to Shakespeare and the language of stars. The capacious mind, the infinite moment, the Virginia Woolf read today.

*

Many other writers have chosen to publish their own works, of course. Unable to find an interested publisher for his revolutionary poetry, Walt Whitman used his own money to finance Leaves of Grass; he designed the cover, chose the binding, and set the type with the help of a local print shop. Berkeley-based author Dorothy Bryant’s second novel was considered so bad by her agent that he refused submit it to publishers, so Bryant and her husband Bob founded Ata Press.

That second novel became The Kin of Ata Are Waiting for You, which was so successful that Random House purchased the rights, and this classic dystopia remains in print, having sold well more than 100,000 copies. Already successful, but dissatisfied with his current publisher, sales-wise, Mark Twain self-published The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (among others). It was not editorial scorn that led him to this venture, but Twain’s entrepreneurial drive.

In classical Rome, an age when most books were still papyrus scrolls copied by slaves and incredibly expensive, writers often stood on pedestals in the market square and read aloud from their works. Fire-side Bards have for millennia sung their songs without benefit of intermediaries. Self-publishing—often disparagingly called Vanity Publishing—has always been a viable course for writers to achieve what they most want: To put their words before readers.

*

After 7 books with mainstream publishers, I decided in 2020, having embarked on a new novel, that I would publish it myself. I had spent decades in the book world, as a bookseller and in publishing. The time had come, I felt, to gather those experiences and create, from inception to bookstore shelves, my own book-object.

After three years of writing and revising, I contacted a well-referred print-on-demand company and began. I commissioned artwork, designed the cover, back and front and spine. I experimented with texture and feel: glossy or matte finish? white or crème paper? I researched hundreds of typefaces until I found one that excited me as a reader, both airy and bold: Monticello. I copy-edited and proofed the manuscript dozens of times, aligned the text blocks meticulously, rooted out hyphen- and word-stacks, evicted the widows and orphans.

A book in the hand beats even the flashiest marketing. A book may begin in the writer’s mind, but it only comes alive when the reader holds it.

Though my hands never got as inky as Virginia’s, they were on every aspect of the book. When the carton of the first 20 copies arrived, I opened it with trepidation. The cover was flawless, the case, paperback, solid but supple. The cover did not curl when face-up on a table, the spine did not crack, and it smelled like a real book. The thrill of reading the first line: “It was the day they shot the students.”

*

During the early years of the Hogarth Press, Virginia Woolf would wander from bookshop to bookshop, a bundle of books in her bag, hoping to convince booksellers to find space on a shelf or table. She understood, as book people do, that a book in the hand beats even the flashiest marketing. A book may begin in the writer’s mind, but it only comes alive when the reader holds it.

I have made a beautiful book, but to complete my book biz journey, I will go on the road again, a box of books in the trunk of my car, and drive from bookstore to bookstore, seeing old friends and making new ones. In every shop I visit, I’ll spot the fiction feature table, always near the front door, and imagine where my novel might best fit. If the book is set properly, right there, then a reader might pick it up, smooth the cover with her hands, turn it over, read the back copy, and, if the weather is right, purchase it. She’ll take it home, crack open the first page, and begin to read. Writer and reader, face to face at last.

Lewis Buzbee

Lewis Buzbee is the author of The Yellow-Lighted Bookshop, as well as three award-winning novels for younger readers, Steinbeck’s Ghost, The Haunting of Charles Dickens, and Bridge of Time. Find him at lewisbuzbee.com and @buzbeebooks. His newest novel, Diver, is available wherever books are sold