“Inhabiting the Poem.” Seven Poetry Collections to Read This October

Christopher Spaide Recommends Gbenga Adesina, Cameron Awkward-Rich, and More

“What was the work the poet was demanding of me? It was to inhabit the poem, to live willingly in its world.” Those sentences were written by my late teacher Helen Vendler, and arrive in the second essay of her posthumous collection Inhabit the Poem: Last Essays, just published by the Library of America. Ever since reading the collection this summer, I’ve taken these lines as a readerly dare: not to stand back from a difficult poem, reaching out only to its easy-to-grasp features—its recognizable allusions, its formal flash—but to strive to inhabit every poem in all its standoffish singularity.

In Vendler’s essay, the poem in question is Wallace Stevens’s “The Bird with the Coppery, Keen Claws,” an enigmatic portrait of a paradoxically un-bird-like bird. Flightless, sightless, songless, all but motionless, the bird with the coppery, keen claws baffled Vendler until she resolved to devote herself to him fully: “Once I understood that I had to take the bird literally, peculiar as that seemed, I became his ornithologist, recording the bird’s traits, his present and past habitats, his powers, his hindrances, and his actions.” (What poetic bird could do better than that—Helen Vendler as his personal ornithologist?)

In book after book, the fall’s new poetry challenged me to inhabit the poem; no two experiences were remotely alike. Geographically, I was transported to the Standing Rock Reservation in 2016, as seen by Teresa Dzieglewicz; the Nigeria of Gbenga Adesina’s childhood and the Brooklyn of his adulthood; and Palestine, encapsulated first in a foundational 1970 anthology then again 55 years later. I dwelled in poems composed within curious strictures of genre and form: Mandy Moe Pwint Tu’s fables, Bruce Smith’s dozens of ten-line stanzas, seven poems Cameron Awkward-Rich gives the same Dickensian title. Just once, I found myself inhabiting the poem right where I sat.

The last piece in Susan Briante’s 13 Questions for the Next Economy: New & Selected Work is titled “No Where Is Outside Mississippi,” and it takes inspiration from the civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, one of Mississippi’s own, and from student activists at Emory University who, in the spring of 2024, demonstrated against Palestinian genocide, the training campus known as Cop City, and politicians and administrators writing off activists as “outside agitators” by declaring there was no “outside”: “Emory is Everywhere.” I live in Mississippi. Before moving here, I spent the 2023–2024 academic year at Emory; I taught those students, who can now add “inspiring new poems” to their long list of accomplishments. Sometimes, to inhabit the poem, all you have to do is inhabit your world.

*

Gbenga Adesina, Death Does Not End at the Sea

(University of Nebraska Press)

Longlisted for the National Book Award, Gbenga Adesina’s first collection Death Does Not End at the Sea begins with a song of praise—“Glory of plums, femur of Glory. / Glory of ferns / on a dark platter”—swaddling a death announcement:

Glory of the eyes of my father

which, when he died, closed

inside his grave,

and opened even more brightly

inside me.

The book ends, nearly a hundred pages later, with an “Elegy of Hands,” and Adesina’s eyes playing tricks on him; the far-off sight of “a white cluster, a crown of egrets” turns out to a cemetery: “It was as though the gravestones were holding hands. // It was the kind of thing that would have made him laugh.” In between those two poems and their sightlines (one widened by grief, the other warmly distorted), Adesina runs through one genre and narrative angle after another in his studies of his life’s most pressing absences: the late father he imagines carrying on his back, lashed to him with his hospital IV tubes; the world-traveling James Baldwin, now nowhere to be seen in Paris, Istanbul, or Senegal. The book’s title sequence, a saga of people and ghosts at sea, aims for nothing less than the polyvocal clamor and planetary scale of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and Robert Hayden’s “Middle Passage”: “I’m writing toward our choral country.”

Naseer Aruri and Edmund Ghareeb, editors, Enemy of the Sun: Poetry of Palestinian Resistance, with a new preface by Greg Thomas

(Seven Stories Press)

“Tragedy is accepted to mean a sequence of events seemingly inevitable, exciting pity and fear and leading to disaster. It is hard to escape the chilling impression that this describes the state of affairs in the Middle East.” Do those sentences strike a chord? Presumably they did in 1970, when they opened Samuel W. Allen’s preface to Enemy of the Sun: Poetry of Palestinian Resistance, the first anthology of Palestinian poetry published in the United States; the book was published by Drum & Spear Press, the short-lived publication wing of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. (A handwritten poem titled “Enemy of the Sun” was found in George Jackson’s cell after his killing and soon published under his name; in truth it was written by the Palestinian poet Sameeh Al-Qassem.)

Long available only in passed-around copies and invaluable scans, Enemy of the Sun has been republished by Seven Stories Press in a new edition that supplements the original edition’s twelve poets, translated by the editors Edmund Ghareeb and the late Naseer Aruri, with over a dozen more writers, ranging from the assassinated political leader Kamal Nasser and his mother Wadi’a Nasser (whose elegy “My Son Kamal” ran on the front page of Jerusalem’s Arabic-language newspaper) to Palestinian and Arab poets writing today. Following the original edition’s practice, the new edition prints authors’ names in the table of contents but not before or after the poems themselves.

Read cover to cover, the anthology reads as the improvisatory formation of an anonymized chorus, with individual voices including the twentysomething Mahmoud Darweesh (“Record! / I am an Arab / without a name—without title”) and the contemporary poet and doctor Ali Ibrahim Al-Tawil, documenting the horrors just outside: “In Gaza, the water queue is a form of ‘The / Postponed Death’ in life.” (This fall brings another unmissable English-language anthology of Palestinian poems: You Must Live: New Poetry from Palestine, translated and edited by Tayseer Abu Odeh and my friend Sherah Bloor.)

Cameron Awkward-Rich, An Optimism

(Persea Books)

The peculiar title of Cameron Awkward-Rich’s boldly ambivalent third collection, An Optimism, forks in contrary directions: either there are multiple optimisms—here is an optimism, one among many—or, following negative words like anarchy or anhedonia, this is a book about anoptimism: the absence of optimism. By the time, two-thirds in, that Awkward-Rich traces his title’s origins to a line of June Jordan’s—“But life itself compels an optimism”—the book has seen optimism and anoptimism aplenty, even in the same poem: “Oh, I know all arguments for / and against my life—.” (And the arguments for and against Jordan too: “My students are so taken by / June Jordan’s conviction / In the generative force / Of language…I am not so sure.”) For evidence for and against optimism, Awkward-Rich scours the archives of Black, trans, and queer writers, sometimes addressing letters to “some particular, impossible you” in the past (here, the activist Pauli Murray), elsewhere conducting a multiform “Trans Study” of a monumentalized artwork—Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic.” And in seven poems Awkward-Rich looks over his younger years, a time of sexual innocence and discovery, a time before transitioning (“I was there to start a new life”) that nevertheless set the present’s terms (“it had, therefore, always / been this way”). All seven bear the same title, plucked from Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities: “It Was the Best of Times, It Was the Worst of Times.” Who could disagree?

Susan Briante, 13 Questions for the Next Economy: New & Selected Works

(Noemi Press)

I came late and gratefully to the work of the American poet Susan Briante, all thanks to her latest book Defacing the Monument (2020), a hybrid of prose poetry, literary history, documentary theory, and unorthodox pedagogy, all perfumed with the smoldering dissent of The Anarchist Cookbook. However you choose to classify it, I’m thrilled it’s excerpted in Briante’s 13 Questions for the Next Economy: New and Selected Works, which shuffles together uncollected poems, selections from her previous four books, and (in a different sense of “selected works”) zine-like collages of photocopied documents and images, with the occasional marginal note scribbled in (the first note, immediately following the title page, reads in thick Sharpie, “This book is about money!”). The title itself sounds like something photocopied, a teasing appropriation from any old business-news listicle.

But Briante means it: her title poem situates us on a collective road to nowhere, lined with people in dire need of healthcare and predatory billboards: Disability hearing? Trouble with Social Security? Briante’s first question: “Where does the riot begin?” For Briante, questions of political economy are always existential questions, for our generation and every one to come: “What revolution will my daughter feed?”; “Who will read this // in the next economy, the one that comes after the one that kills us?”

Teresa Dzieglewicz, Something Small of How to See a River

(Tupelo Press)

I can’t think of a poetry collection with a backstory anything like Teresa Dzieglewicz’s Something Small of How to See a River; she’d be the first to tell you that she’s not the star of it. In August of 2016, Dzieglewicz visited the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ Camp on the Standing Rock Reservation, one of three main camps established by protestors of the Dakota Access Pipeline, then under construction. Planning to stay for only a few days, she ended up staying and co-directing the camp’s school, Mní Wičhóni Nakíčižiŋ Owáyawa (Defenders of the Water School), founded earlier that month by Alayna Eagle Shield. The poems of Dzieglewicz’s first book span from that August to the next, when she returned to Očhéthi to see what remains: “The state / can take but not erase the hooves that spoke small o’s // along the dirt, or the log the kids climbed, hemmed now / in clover.”

Dzieglewicz comes to Standing Rock with a naturalist’s trustworthy eye and her moral compass out, and she comes as a white American visitor eager to listen to Indigenous kids, colleagues, and elders: the collection is punctuated with quotes from her students, and one of its most poignant poems is a polyvocal collaboration with Alayna Eagle Shield and her great-great-grandmother Moving Robe Woman. She comes, finally, as an educator and someone ready to be educated. Something Small of How to See a River is a book of instructions, folk etymologies, reading exercises on headlines and police statements, and lessons that stay true hundreds of miles away and years on: “But the Missouri and the Mississippi / become one and reach me, even here, / each time I turn my tap.”

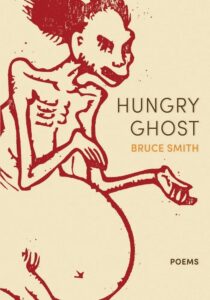

Bruce Smith, Hungry Ghost

(Arrowsmith Press)

Ever since reading his sixth collection Devotions (2011) and becoming a fan on the spot, I’ve always thought that Bruce Smith is the Bruce Springsteen of American poetry. Once you get past the easy, lazy similarities (the closeness in age, the “S” last names, the Bruceness of it all), you’ll find shared virtues rare enough in rock, rarer still in contemporary poetry: the tough love, the tuneful machismo, the literariness worn lightly, the workwear of white American men worn with a self-conscious but accepting shrug. In his eighth collection Hungry Ghost (not “Hungry Heart,” Jack), Smith compacts his riffing and rhyming facility within a rigid frame: nearly all of the book’s poems are built from a blocky ten-line stanza, like a sonnet stopped short, too stubborn to turn.

In Smith’s hands, a single untitled stanza becomes the perfectly constricting playing field for a rant transcribed at lightspeed, or a set of variations on a theme or phoneme: “O in shadow, O in ozone, / O in home, O in micro-macro, poetry’s Oh – the breath expelled / in private to no one.” Stacked into sequences, Smith’s dizains give him space to pay the ultimate compliment and cede his steamrolling style to someone else’s, as in his echoey elegy for the late Lucie Brock-Broido: “Dear Lu, I called and called and you never . . . / Into which ministry did you go with your Russian / Sable and voodoo? Feeling was tinted by you.”

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu, Fablemaker

(Gaudy Boy)

Do you have what it takes to be a fablemaker, the title Mandy Moe Pwint Tu gives herself in her first full-length collection? If not, she’ll teach you, in the conspiratorial directives of her opening poem “Dear Fellow Fablemaker”: “If you find yourself at a yellow door, // knock three times. Only three. // Any more and you will scare the cat.” Elsewhere she’ll show you how to think with a fabulist’s casual outlandishness, how to find the universal in the miniscule, the mystic in the domestic: “Every time I crack an egg I think of skulls.” Through self-made fables, Tu fills in her background with equal doses of fiction and nonfiction, highflying conceit and grounded autobiography. Mandatory conscription in her home country, Myanmar, is instructively explained in a “Fable with Frogs”: “Mother Frog weeping, clutching her son’s // webbed feet, her tongue like bamboo shoots // in her mouth. He’s too young, she begs.”

The distance between father and daughter morphs into the difference between birds of prey and deep-diving fish, until a sudden death confuses the fable’s terms: “When he died, I found a feather tucked under // my scales. I named it grief. I wrote with it.” Tu’s fables wouldn’t lodge in the ear and the memory if she weren’t an assiduous form-maker as well. In a hybrid of two Burmese poetic forms she terms the yuzana, Tu rhymes each short syllabic line with a word tucked inside the next (read these lines out, follow the bolded words): “Wisdoms scatter in the air / riddling bare. Tell my father— / or rather, show him this.”

Christopher Spaide

Christopher Spaide is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Southern Mississippi. His academic writing on modern and contemporary poetry (as well as music and comics) appears in American Literary History, The Cambridge Quarterly, College Literature, Contemporary Literature, ELH, The Wallace Stevens Journal, and several edited collections. His essays and reviews and his poems appear in The Boston Globe, Boston Review, Lana Turner, The Nation, The New Yorker, Ploughshares, Poetry, Slate, and The Yale Review, and he has been a poetry columnist for the Poetry Foundation and LitHub. He has received fellowships from the Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry at Emory University, the Harvard Society of Fellows, the James Merrill House, and the Keasbey Foundation; for his academic writing and criticism, he has received prizes from Post45 and The Sewanee Review. Currently, he serves as the Secretary for The Wallace Stevens Society. He is the literary executor for Helen Vendler.