Ingmar Bergman Made a Movie For Each One of His Fears

Failure, Illness, and Other Terrors That Haunt His Films

As a writer I often feel like I am in trouble. This is something a writer should never say or admit to feeling. Not if they want to continue to write and not if they want others to think of them as writers who know how to write. Writing produces constant dread and anxiety: the feeling that I have to write, but can’t. That I don’t know how or never will again. This is how writing starts. This means that writing is not simply what I do, it is also what I cannot do and might never do again.

In the documentary Bergman Island (2006), Ingmar Bergman makes a list of his demons and then reviews each one on camera. Bergman admitted to having many fears, but the one fear he said he never had was the “Demon of Nothingness,” which is “Quite simply when the creativity of [your] imagination abandons [you]. That things get totally silent, totally empty. And there’s nothing there.”

Bergman Island ends with Bergman describing a fear that he claims to have never had, to have never even known, and which his huge body of work (63 films) corroborates to some extent (the way that a corpus of work always corroborates the ability rather than the inability to work), but which nevertheless burrowed into his life in other ways: his films, which featured characters, often artists—both men and women—grappling with the fear of Nothingness. In Bergman’s films, characters wrestle with being abandoned and betrayed not by their imaginations—for fears produce their own fantastic fiction—but by the inability to creatively hone, represent, and endure those imaginations.

In Bergman Island Bergman also talks about the Nothingness of death. The way he thought about and was “touched” by death every single day of his life. Then one day, while under anesthesia for an operation, he realized that because death is nothing (“a light that goes out”), it did not need to be feared. The love that Bergman felt for his last wife, Ingrid von Rosen, to whom he was married (after many other marriages) for twenty-four years until she died, forced him to once again reevaluate death and whether or not death effaces Nothingness. Bergman loved Ingrid, wanted to feel her presence after her death; wanted to be reunited with her, and therefore couldn’t allow himself, he says, to see death as an end to life, for that would have meant an end to Ingrid too.

I watched Bergman Island and Bergman’s 1968 gothic horror, Hour of The Wolf, at the same time. I considered them companion pieces. I was heartbroken after a breakup and struggling with my writing. The two films confirmed how difficult and elusive creative work is. What motivates one person to work, resulting in hyper productivity, is the very thing that makes working impossible (paralyzing) for others. While some people work in order to avoid thinking about what is behind their working— that is, in order to not think about what is not working; what doesn’t get recovered and compensated for by work—others work as an attempt to fix, evade, or control what is not working.

You’ll find a Bergman film for every single of one of his fears.

For some, work works. For others, work fails to work. Bergman Island reveals that while Bergman (who died a year after the documentary was released) managed to kick the fear of Nothingness, as far as death was concerned, he continued to harbor the rest of his demons. Because fears free-associate and mesh— induce and house other fears; the way one fear can unveil and morph into another—the fears that plagued Bergman throughout his entire life could have easily mutated into the catchall fear of Nothingness, with respect to his creativity. Yet rather than not work because he was afraid, or reject fear as a source of inspiration, Bergman often made films about fear and in the face of fear. Made fear the subject and his subjects afraid. He did not ghettoize fear. Nor did he restrict it to the genre of horror.

If you pay attention to Bergman’s list of demons in Bergman Island, you’ll find a Bergman film for every single of one of his fears. You’ll find a film in every demon and a demon in every film. For Bergman, the process of and reason for making a film was partly about what it means to be creative without mythologizing or romanticizing creativity, or even proposing it as an outlet or antidote to the anxiety work simultaneously alleviates and produces. I don’t think Bergman believed creativity was capable of softening the blows of fear and doubt. He focused instead on what it means to give up the idea of mastery and control in order to explore something more grave—debilitation. Many of Bergman’s characters make themselves sick.

In Wittgenstein (1993), Derek Jarman establishes a similar trajectory regarding the trauma of knowing. Of what it means to know and the ways in which knowing can disable as well as enable one to live. In Jarman’s film, the search for knowledge does not mitigate the trauma of knowing. For Wittgenstein, “knowledge” results in one epistemological and ontological crash after another. The Austrian philosopher slides between different multiplicities and temporalities. Wittgenstein is simultaneously weak and sick, child and adult, Austrian and English (the slippages in accent; the slippages in everything), active and passive, hopeful and despairing, brilliant and stupid, gentle and tyrannical.

Both Wittgenstein and Blue (1993) take potentiality and finitude as their philosophic start-up positions. Wittgenstein is a trans-subjective subject, appearing in the film as the child-philosopher because it is the child who has view of the future. What Wittgenstein—the-child— knows, he has always known. And also, could not have known yet and might never know. Uncertainty and doubt belong to the adult Wittgenstein. It is Wittgenstein-the-man who writes (in the Tractatus), “What’s more important about philosophy is all the things philosophy can’t articulate. Can’t say.”

Fear simply requires a direct stake or address—the naming of that which is unnamable.

Despite Bergman’s assertion that his creativity never failed him, never fell silent, Bergman made Hour of the Wolf, in which Johan, an artist, is unable to paint, and Persona (1966), in which the stage actress, Elisabet Vogler, stops speaking. It isn’t clear, however, which fear blocks Johan and Elisabet, or if the fears in these two films can even be classified. For both Alma and Johan one fear leads to another and creativity exposes one to a topology of fears that threaten it.

For Bergman, fear doesn’t always need a direct object. As he illustrates with his catalogue of demons in Bergman Island, fear simply requires a direct stake or address—the naming of that which is unnamable. Like Alma (Elisabet’s nurse), who speaks and doubles for Elisabet in Persona, Alma (Johan’s wife) in Hour of The Wolf, suffers the blows of Johan’s unspeakable fears. Johan’s fear is the source of Alma’s fear. She fears for his fears, fears for herself, and is afraid of him because of it. Thus, it is the terrified Alma who, on their way back from the party at the castle, tells Johan: “I’m nearly sick with fear… I can see that something terrible is happening. Just because it can’t be called anything.”

Hauntings are always encrypted in writing. Success haunts work. Failure especially haunts success. Success is mostly a reflexive (exterior) phenomenon that is marked by avarice. No one feels successful, they only appear that way to others, and that is one reason why we work—to appear to be living a certain way. Derrida would call this the work of mourning (“One does not survive without mourning”). Walter Benjamin (in his essay on Karl Kraus: “He found that [the nerves] were just as worthy an object of impassioned defense as were property, house and home, party, and constitution. He became an advocate of nerves.”), the rights of nerves. The impetus, the energy, the pursuit comes from nerves: nerves as a call to escape or beat nerves; nerves as a way to prove your nerves wrong, especially during the moments when your nerves feel so much greater than anything else in your psychic arsenal. When we work, we are in mourning about the life we cannot live and the living we don’t know how to do and so put in(to) work. One solution is to record the failure in writing.

__________________________________

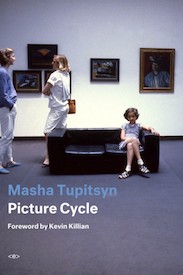

Excerpted from Picture Cycle: Essays by Masha Tupitsyn, Copyright 2019, Semiotext(e). Distributed by The MIT Press.

Masha Tupitsyn

Masha Tupitsyn is a writer, critic, and multi-media artist. She is the author of Love Dog, LACONIA: 1,200 Tweets on Film, and Beauty Talk & Monsters, as well as the films Love Sounds and the ongoing film series, DECADES. Her new book, Picture Cycle, is out now with Semiotexte/MIT.