Indigenous Agency: How Native Americans Put Limits on European Colonial Domination

From Kathleen DuVal's Cundill Prize-Shortlisted “Native Nations”

Guns were not the first European goods Mohawks had seen. Long before Christopher Columbus crossed the Atlantic, perhaps as early as the tenth century, Native North Americans on the northern Atlantic coast obtained goods from Norse explorers. By the late 1400s, glass beads and pieces of wrought iron and brass were arriving by way of trade with European fishing boats or as detritus washed ashore from shipwrecks. Mohawk towns acquired some of those goods, either through trade or by raiding.

Although Europeans were the most direct source of European manufactured products, most Native communities got these goods through Native traders. Initially the Mohawks used European goods as raw materials. Strips cut from a copper kettle made lovely pendants and rings that could demonstrate the wearers’ or givers’ connections beyond their towns and region. Pieces of an iron knife could be made into needles for many people to use in sewing and tattooing. Years before the 1609 battle in which Mohawks first encountered muskets, Algonquians began placing bits of iron and brass on the tips of their arrows, increasing their chances of shooting through Mohawks’ wooden armor, and Mohawk warriors, when they could get metal, did the same.

If we rush too fast through the seventeenth century, we might interpret the arrival of guns and metal-tipped arrows as the start of Native dependence and European dominance. But we would be wrong. Local rivalries, customs, and geography continued to be the most important factors in Native decisions and determined the opportunities and limits for Europeans. There had been new weapons here before, and new ways of defending against them. When your enemy gained some advantage, you adapted, and that is what the Mohawks did.

Native Americans wanted European trade, but almost all European efforts in the sixteenth century had failed. French, English, or Spanish would-be colonizers typically came blustering in without sufficient or steady supplies of goods for local Native populations or even enough food for themselves. Locals threw them out, or they abandoned the ventures as quickly as they came. By the early years of the seventeenth century, Europeans had established a handful of North American posts that lasted because they either found ways to be useful to local Indigenous people or brought enough military men to defend themselves.

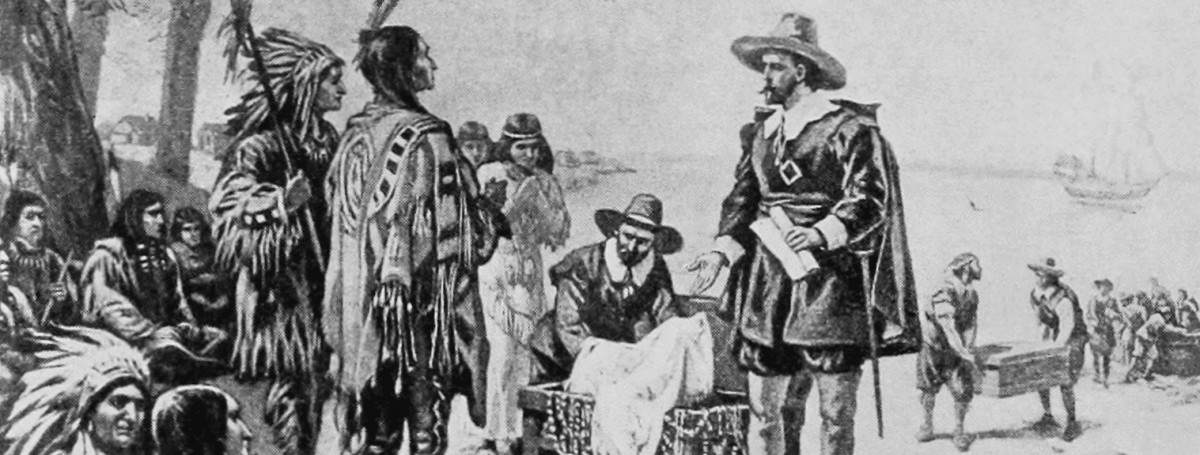

In addition to Spain’s St. Augustine and Santa Fe, the English began Jamestown in 1607, and the French established the town of Quebec in 1608. Closer to the Mohawks, in 1609, Henry Hudson, hired by the Dutch to look for a northwest passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, sailed partway up the Hudson River, and Dutch ships subsequently began coming annually, with metal and beads and jewelry to trade for furs and food.

Local rivalries, customs, and geography continued to be the most important factors in Native decisions and determined the opportunities and limits for Europeans.

When the French established Quebec in 1608, it was on Innu land and because Innu leaders invited them. Like many Native Americans, they drew Europeans and their weapons into preexisting North American conflicts. The Innu and their Algonquin and Wendat allies wanted a steadier source of French goods and hoped to lure French soldiers into fighting with them against the Mohawks.

*

In many ways, the Mohawk Valley was the perfect place to live. Sheltered by the mountains and well watered by rain and rivers, it offered extremely fertile soil, while the woods and meadows hosted plentiful game and natural resources. Another advantage was that all rivers flow away from Haudenosaunee country—the Mohawk River flows east into the Hudson, and the rivers of the other four Haudenosaunee nations run west to Lake Erie or south into the Susquehanna and Allegheny watersheds—making it hard for enemies to get to.

But when European trade came to the Atlantic coast, suddenly Native communities downstream had an advantage, because they were closer to the ports. As the “keepers of the eastern door,” the Mohawks would be responsible for European diplomacy and trade for the Haudenosaunee. Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence River had long been part of Mohawk travels, and soon after the first enemy hit a Haudenosaunee target with a metal-tipped arrow, Mohawk warriors began waylaying Algonquin and Wendat traders returning home up the St. Lawrence with kettles and other European goods. Yet the French, vastly outnumbered, preferred not to give even their allies guns. As a result, Mohawk raids seldom put guns in Haudenosaunee hands, and Wendats, Algonquins, and Innu made it hard for the Mohawks to reach French posts. Enemies to the south also blocked Haudenosaunee traders from the English at Jamestown.

But a closer opportunity arose in the 1610s, and the Mohawks did everything they could to develop it. An old history textbook, if it includes New Netherland at all, might say that colony was founded by Dutch traders boldly going inland in search of furs. In fact, Native people—the Munsees and related Lenape/Delaware groups on the lower Hudson and Delaware rivers and Mohawks and Mahicans up the Hudson—actively encouraged Dutch trade and settlement.

*

It turned out that the early-seventeenth-century Dutch were the best possible trading partner for Mohawk purposes. Their shipping was on the cutting edge of European technology, and Dutch weapons manufacturing was the most advanced in Europe because of their war against Spain. Dutch innovators developed the mass-produced flintlock musket in the 1620s. Flintlocks fired using the friction of a flint, making them more dependable than matchlocks (which ignited the charge with a cord that had to be kept lit) and easier to produce than wheel-lock muskets (which employed friction through a more intricate mechanism). Dutch mass production of weapons would supply both North America and the Thirty Years’ War in Europe, which started in 1618.

Mohawks kept rivals from trading with the Dutch, even if they were Haudenosaunee. They traded goods on to the Haudenosaunee to their west but did not invite them to come to Fort Orange themselves. Indeed, when Oneida or Onondaga traders tried to cross Mohawk country to reach the Dutch, the Mohawks waylaid them. To them, their role as the keepers of the eastern door included being the providers of Dutch goods to the rest of the Haudenosaunee.

As the Dutch colony of New Netherland grew, a great many Dutch guns would end up in Mohawk and other Haudenosaunee hands. Mohawks would return home from the Dutch post at Fort Orange bearing goods from Europe, which came up the Hudson River from the post that the Dutch had founded on Manhattan Island: New Amsterdam.

*

Like the French, West India Company officials tried to stop the munitions trade, even passing an ordinance levying the death penalty for arms sales, yet the Mohawks wanted to buy guns, gunpowder, and musket balls, and these goods were the only way Dutch traders could buy enough beaver pelts to make New Netherland worth having at all. Selling guns earned them huge profits. For one gun a Dutch trader might get twenty beaver pelts. He could trade those twenty pelts in Europe for ten guns to take back to Mohawk country and trade them for more furs.

Everyone ignored the prohibition on arms sales, all the way up to the colony’s highest officials. Some of Albany’s most prominent families made their wealth from dealing in guns or related industries. Philip Pieterse Schuyler—the great-great-grandfather of Eliza Schuyler, the future wife of Alexander Hamilton—moved from Amsterdam to New Netherland as a gunstock maker around 1650 and also traded in furs and brandy.

Before long, it became clear that if the Mohawks couldn’t purchase weapons from the Dutch, they would buy them from someone else. New Netherland governor Peter Stuyvesant in 1654 justified violating company policy by explaining that “Mohawks, now our good friends,” had told him that they “have been out of necessity forced to seek munitions” from the English. Starting in the 1630s, English traders in the Connecticut Valley paid better prices for their beaver pelts and gave them “substantial presents and gifts.” If the Dutch refused the Mohawks, Stuyvesant continued, “it might well follow that we would also lose the Mohawks’ friendship and consequently burden our people and nation with more misfortune.”

Therefore, he and the New Netherland Council “deemed it proper and highly necessary” to provide the Mohawks with “a moderate trade in munitions.” Haudenosaunee men eventually began making their own musket balls out of bars of lead, and a craftsperson who could make an arrowhead could replace the flint in a flintlock musket, but Mohawks kept coming to Fort Orange for new guns, significant gun repairs, and gunpowder. If New Netherland hadn’t provided goods and services that the Mohawks wanted, it would have ceased to exist.

*

Mohawks came to Fort Orange for the guns, but they stayed for the cake. When they visited Fort Orange and nearby Rensselaerswijck, they sampled Dutch cakes, cookies, and bread and took some home for others to try. The excellence of Dutch baking was universally recognized. The English word “cookie” comes from the Dutch koekje. Mohawk women made cornbread, but it may have seemed dense and mundane when compared with the treat of an airy yeasted white bread, fine cake, or cookie after making the trip to Fort Orange with a load of beaver furs and baskets of corn. To the frustration of many colonists, Mohawks’ proceeds from the fur trade allowed them to pay high prices. The Dutch colonists who introduced white bread and cakes to the region soon could not afford them.

Colonists repeatedly complained to the New Netherland Council that bakers sifted whole wheat flour and sold the white flour “greatly to their profit to the Indians for the baking of sweet cake, white bread, cookies, and pretzels,” leaving “largely bran” to sell to the townspeople. The petition concluded in horror: “The Christians must eat the bran while the Indians eat the flour.” In an effort to appease colonists, the council outlawed the sale of white bread and cake to Native customers, but, as with liquor and guns, Native demand prevailed. Bakers continued selling baked goods made from white flour to their best customers.

By high summer, hundreds of Mohawks—some years as many as a thousand—lived in Rensselaerswijck for weeks at a time, sometimes outnumbering the few hundred colonists. Some camped in fields and around town, and others stayed with Dutch or Mahican hosts. Some Dutch men and women built houses specifically for trading with and lodging customers—you can see them on colonial maps, marked as “little house” or “Indian house.”

Others reserved space in their front rooms for trading and socializing with Native men and women, selling them homemade beer, milk, butter, and cheese and letting them sleep on the floor. One Dutch colonist observed with disdain that, “not being satisfied with merely taking them into their houses in the customary manner,” some had tried to attract “them by extraordinary attention, such as admitting them to the table, laying napkins before them, presenting wine to them and more of that kind of thing.”

While this kind of hospitality seemed excessive to European observers who saw Indians as dangerous and perhaps savage, it was necessary for anyone who wanted Mohawk customers. Despite the efforts of the colonists waylaying them on the road in, Mohawks generally would go farther into Rensselaerswijck to enjoy the hospitality of individual houses and farms. In addition to cake and bread, men chose gunpowder, iron tools, shirts, and fishhooks, and women picked out hoes, awls, fabric, ribbons, and buttons. Mohawks and Dutch colonists alike carried wampum around town in elaborately decorated bags made by Mohawk women.

In Rensselaerswijck, Mohawks also observed aspects of Dutch life that impressed them less than muskets and cake. One Sunday morning, a group of Mohawks went into the church to hear Dutch minister Johannes Megapolensis preach. As they listened, they smoked their long tobacco pipes, catching a few Dutch words here and there. At the end of the service, they asked the pastor why he wanted to “stand there alone and make so many words, while none of the rest may speak.” It was the opposite of Haudenosaunee meetings, where each had the chance to talk. Megapolensis explained that he was “admonishing the Christians, that they must not steal, nor commit lewdness, nor get drunk, nor commit murder.” Having observed all of this behavior in New Netherland’s posts, and probably Dutch drunkenness just the previous night, the Mohawks replied that the admonishments didn’t seem to be working.

Because Mohawk and Dutch women both had public roles in the economy, Native and European women interacted in Rensselaerswijck to a greater extent than was usually the case in colonial relationships. Like many Native women, Mohawk women traded the corn and other food they produced and bought the goods they wanted, and they probably also had some say in the sale of the furs they had processed. In this respect Dutch settlers were more similar to Mohawks than other Europeans were. While most European societies undervalued women’s economic contributions and kept them out of international trade, the Dutch were somewhat less patriarchal, at least when it came to business.

By the 1660s, New Netherland was a fairly stable colony, with between seven and eight thousand colonists, but its stability resulted from people’s adopting one another’s ways when useful and otherwise rejecting them without much conflict—as in the case of the Mohawks listening to the sermon. Many of the Mohawks’ relationships with their neighbors did not go this smoothly, so the Dutch were lucky. And Mohawks were lucky that they faced colonization not in the unruly times before the forming of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy but with a large and reasonably united population on their homeland. The Dutch could be dangerous and brutal, as evidenced by their involvement in the Atlantic slave trade and plantation slavery in the Caribbean, as well as occasional violence against Munsees and Lenapes along the lower Hudson River.

Colonists in seventeenth-century North America were seldom able to achieve colonialism’s exploitative goals, though not for lack of trying.

By the mid-1600s, if you visited a Mohawk town, you could see how they had incorporated European consumer goods into their material culture, alongside older goods and customs. At first glance, the town would have looked like Mohawk towns in the previous century, with several dozen longhouses built of local materials and covered in bark. But a closer look would reveal signs of the new economy as well. Parts of the buildings were held together with iron nails, and the interior doors were made of imported split planks of wood and hung on iron hinges. Iron simply worked better for some things than stone or copper. Indeed, iron was such an important addition that Mohawks sometimes called the Dutch Kristoni, meaning “I am a metal worker.”

In among the bearskins you could also see wool blankets. If it was winter or early spring, beaver pelts were stacked in the corners by the hundreds, ready to take to Rensselaerswijck. Mohawk men often wore linen shirts imported from Europe, because they were breathable and comfortable. But they didn’t wear them the way European men did, tucked into pants under a coat. They wore the shirts basically like slickers, untucked over leggings, and they greased the linen to make it waterproof. They rejected European pants as much less practical than their deerskin leggings. In parallel, Europeans, including soldiers and officers, adopted moccasins because they were superior footwear. By late in the seventeenth century, every Haudenosaunee warrior had a musket and often a pistol as well, while their enemies still were lucky if they had one for every two warriors.

If you could peek inside a mid-1600s imported brass or copper kettle simmering over a Mohawk fire, you would see the same foods that the mothers and grandmothers of the cooks once made in ceramic pots: corn, beans, pumpkins, venison. Kettles made of metal conduct heat better than pottery, so water boiled faster, a particularly important quality when women were making large quantities of food in their communal kitchens.

Before acquiring European trade, North American Indians used copper for jewelry and ceremonial objects, but not for pots, because copper by itself causes a toxic chemical reaction with food. Europeans lined their copper kettles with tin or alloyed them with brass. Still, despite the new kettles, Haudenosaunee women continued to use pottery and probably made even more than before, to sell to Dutch consumers for storing and serving food and drink.

Mohawks changed their consumption and production patterns, while at the same time continuing many of the practices and beliefs of their ancestors. They increased their production of beaver pelts by adding to their usual summer hunt an additional hunting and raiding season in early winter, when beavers’ pelts were thickest and when women did not need the men for the labor-intensive work of preparing fields in the spring or harvesting crops in the fall. Then Mohawk women could scrape and process the furs in the heart of the winter, when they had no work in the fields. Mohawks even wore the new furs for warmth that winter so that by spring they were broken in and softer and thus more valuable on the market.

Haudenosaunee production supplied the European market, while Haudenosaunee demand also had global consequences. Mohawk scholar Scott Manning Stevens points out that, while the tomahawk became the quintessential symbol of Indians, in fact tomahawks were manufactured from metal and wood in Europe, specifically for Native markets. European factories made goods to Indian specifications, including heavy woolen cloth in a variety of specific sizes and colors for different Native nations.

Early on, Dutch traders learned that red cloth wouldn’t sell, “because the Indians say that it hinders them in hunting, being visible too far off.” Dutch flintlock muskets destined for the Haudenosaunee were made half as heavy as other muskets, at their request, because lighter guns were better for hunting and raiding. Some French-made guns featured a serpent-shaped side plate (the metal opposite the lock plate), signaling that they were designed and made for American Indians. To their buyers, they advertised the fearsome power of the serpent. The Dutch began manufacturing kettles specifically for the Native American market as early as the 1610s.

It is only stereotypes of Indians as primitive that make their power to transform markets surprising. Mohawks could hunt and process furs and hides efficiently, and in return they got products they needed or wanted. Manufacturing on both sides responded to demand. European traders complied with Native requirements to embed trade within relationships of alliance, renewed regularly with ceremonies and speeches. Colonists in seventeenth-century North America were seldom able to achieve colonialism’s exploitative goals, though not for lack of trying. Instead, Mohawks and most others who established commercial relations with Europeans in this era had the power to control the terms of trade and to draw Europeans into their alliances and wars.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Native Nations: A Millennium in North America by Kathleen DuVal. Copyright © 2024 by Kathleen DuVal. Reprinted by permission of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Kathleen DuVal

Kathleen DuVal is a professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she teaches early American and American Indian history. Her previous work includes Independence Lost, which was a finalist for the George Washington Prize, and The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent. She is a coauthor of Give Me Liberty! and coeditor of Interpreting a Continent: Voices from Colonial America.