In the Mississippi Woods Where the Southern Myth Ends

W. Ralph Eubanks Gets Deep Into the Piney Woods,

Literary and Otherwise

On the trip north from the coastal lands of Mississippi—with their beaches and creole-influenced culture—the landscape and sensibility of the state begins to change. It’s something Michael Farris Smith’s characters notice as they trudge along Interstate 55 toward the south Mississippi town of McComb in Desperation Road: Even in the dead of winter, south Mississippi awakes with a hint of green. That green remains prominent in the southern part of the state because of the vast pine forests that blanket the region, a sign you have entered the Piney Woods. Once a dense forest, the Piney Woods are part of a broad coastal plain that stretches from southern Virginia to East Texas.

In 1862 historian J. F. H. Claiborne wrote in Harper’s that Mississippi’s Piney Woods was a place that “sustains a magnificent pine forest, capable of supplying for centuries to come the navies of the world.” Claiborne even wondered if the Piney Woods was the location of the miraculous fountain sought out by Ponce de León in the sixteenth century. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries logging took whole swaths of the Piney Woods, leaving behind what you see today: a prairie land of softly rolling hills dotted with pine trees. Mississippi’s Works Progress Administration WPA Guide only devotes one paragraph to this region of the state, noting that the Piney Woods “is a rather haphazard and irregular triangle, whose scenery of stumps, ghost lumber towns, and hastily reforested areas tells its saga.”

While logging is no longer the dominant industry of the Piney Woods, it is stamped on the region’s identity. Logging yards can still be found on remote rural roads, and the once-booming rural communities that revolved around the logging industry are not yet ghost towns but hang on, evidence of the scrappy survival instincts of the people. This is a part of the state that sought to remake itself after the Civil War, with lots of tidy little towns that sprang up along new railroad lines. These were Southern spaces, though not the same Southern spaces as defined by the rest of the state. Much of the Piney Woods was essentially frontier well into the 20th century, which has led many to see this part of the state as a place where not much happened.

Piney Woods native and Thurber Prize–winning humorist Harrison Scott Key sees the Piney Woods as an area that is hard for many Mississippians to describe. “We have few great battles, no particular music, and only a handful of notable residents from the last hundred years. Most folks from the Piney Woods have claimed—or been claimed by—these other regions, due to their cultural magnetism, I think. It’s hard telling people you’re from that part of Mississippi. I just tell people I’m from the bush.”

As a Piney Woods native, I don’t think of this land as being remote like the untamed Australian bush nor do I see it as a haphazard landscape that is difficult to describe. The hills in this part of the state are always a lush green and they roll gently along the landscape, with the occasional setting that mimics the prairie—if the prairie were filled with tall pines. Are we known for music? Well, there are a few musicians from this part of the state, like Sterling “Mr. Satan” Magee from my hometown of Mount Olive. Born in 1936, he grew up attending a Baptist church and worried his mother when he discovered the blues, known throughout the South as the devil’s music. Magee—Mr. Satan to his friends—may be the best-known bluesman from this region, even though he made his mark as a musician and artist on the streets of Harlem.

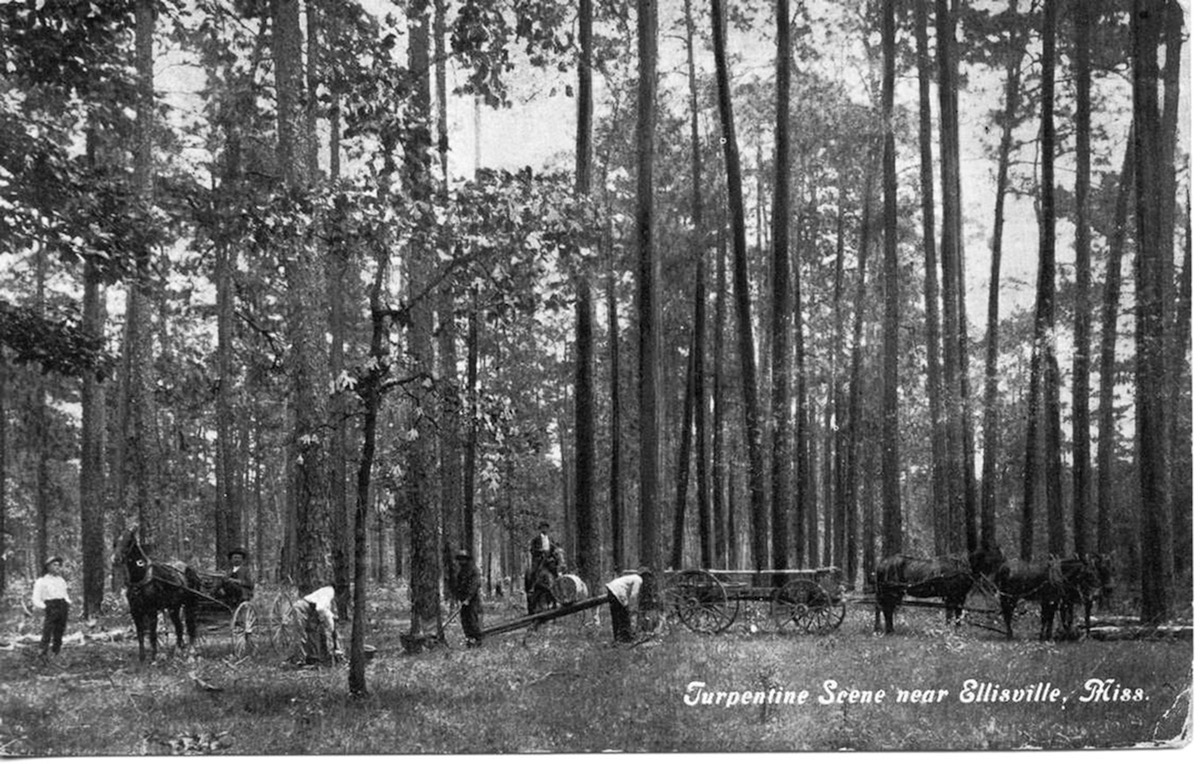

Logging has long been part of the frontier culture of Mississippi’s Piney Woods. This scene outside of Ellisville in 1921 is reminiscent of James Howell Street’s stories of Piney Woods logging and logging communities.

Logging has long been part of the frontier culture of Mississippi’s Piney Woods. This scene outside of Ellisville in 1921 is reminiscent of James Howell Street’s stories of Piney Woods logging and logging communities.

As a family friend who has lived in the region for all of his 93 years told me, this is a place that more than anything is known for holding on to its frontier origins, which means that there are large swaths of land that remain largely unchanged from the way they were in the early 20th century. After my first trip to Ireland in my early twenties, I realized that the hills that make up the pastureland in the Piney Woods must have reminded the original frontier Scots-Irish settlers of the homelands they left behind, particularly in the spring when the morning mist floats over the hills.

While many see this part of the state as just the massive pine forest between Gulfport and Jackson, much more happened in this part of Mississippi than the landscape indicates.

In addition to the place itself, what sustained the frontier settlers of this region was their faith. “My third dream was to make Jesus happy,” Key writes in his memoir Congratulations, Who Are You Again? “I was a member of the Church of Christ, a 19th-century evangelical sect consisting of good country people who believe Satan came in the form of a piano.” Although the landscape may not be haunted by antebellum spirits, it is what Flannery O’Connor would call “Christ-haunted,” since it is dotted by signs promoting the power of prayer. One sign outside the tiny town of Liberty commands that “If you want God to bless America, stop legalizing sin.”

Faulkner scholar Noel Polk grew up in the Piney Woods town of Picayune. It, too, was Christ-haunted; the town once had a sign at its city limits proclaiming, “Jesus is Lord over Picayune.” Polk painstakingly reconstructed Faulkner’s novels as he originally intended, and it was through this work that Polk began to see a difference between his South and Mississippi and that of Faulkner and other Mississippians who hailed from places with more antebellum origins, such as Natchez or Oxford. Picayune and south Mississippi, Polk said, was a place that “did not invest very much of its energies in being Southern in any traditional sense.” South Mississippi was different from the rest of Mississippi and the South, “swaddled as we were in the tall gorgeous pines of the miles-wide strip called the Piney Woods.” In the process, residents of south Mississippi “seem to have done everything we possibly could to avoid calling attention to ourselves.”

Polk believes that residents of the Piney Woods grow up outside the Southern myth, “that portion of Southern history, that part of the public image of the South, that belongs to Natchez, Vicksburg, and Oxford, and that attaches itself to all the rest of us, no matter where we are from.” The Piney Woods has no Civil War battlefields or courthouse squares with Civil War heroes. While many see this part of the state as just the massive pine forest between Gulfport and Jackson, much more happened in this part of Mississippi than the landscape indicates.

From the late 1930s to the early 1950s the frontier culture of the Piney Woods was captured in many of the novels and short stories of writer James Howell Street, born on October 15, 1903, in the sawmill village of Lumberton, Mississippi. His first book Look Away!: A Dixie Notebook included journalistic recitations of stories from his father as well as contemporary events he saw as a reporter. Street wryly remarked that his first book was called Look Away! and everyone did. And while his work is not very well-known today, the stories he collected are rooted in the culture and folklore of the Piney Woods and are ones that every native of the Piney Woods knows. Street said that many of the tales recounted in Look Away! were unpublished tales from his newspaper stories since “newspapers in the South really do not like such stories. Some of them are not pretty.”

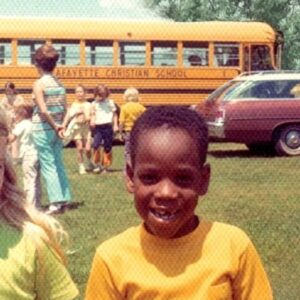

A field outside of Mount Olive.

A field outside of Mount Olive.

The not-so-pretty stories were matter-of-fact reports of lynchings, accounts of violence in the Scotch-Irish settlement of Sullivan’s Hollow—a place Life magazine dubbed “the meanest valley in America”—and the story of Newt Knight, who overthrew the Confederate authorities in Jones County and raised the United States flag over the county. In time he proclaimed it to be the Free State of Jones and had a family with a former slave named Rachel, who was once owned by his grandfather. Later the story and legend of Newt Knight would become part of a five-novel historical fiction series regarding the progress of the fictional Dabney family in the fictional Piney Woods town of Lebanon, Mississippi. The novel Tap Roots from that series reflects Street’s attempt to create a composite character of the Piney Woods settler, more rooted in legend than in truth. Street sought to connect the anti-Confederate sentiments in the Piney Woods to the mixed-race ancestry of some residents of the region. “We can’t boast of our ancestors because, when we get started talking about our families, out jumps the ghost of a pirate or a cousin of color,” notes the character Sam Dabney in Tap Roots.

It would take historian Victoria Bynum, whose roots are in Jones County, to unravel the history of the region behind the mythology James Street created. She begins her 2001 book, The Free State of Jones, with the 1948 trial of Newt Knight’s great-grandson Davis Knight, who was charged with the crime of miscegenation. Tap Roots was released as a film that same year, and this renewed interest in the Knights may have even brought attention to Davis Knight and led to his being tried and eventually acquitted for intermarriage.

In the course of her book, Bynum traces the origins and legacy of the Jones County uprising from the American Revolution to the modern civil rights movement. She takes the legend painted by James Street and compares it with the real story of the Free State of Jones and shows how a place that existed outside the Southern myth still sought to layer that mythology over itself. This approach reveals a great deal about the South’s transition from slavery to segregation and gives another dimension to a region of the state that many believe lacks its own history.

__________________________________

Adapted from A Place Like Mississippi by W. Ralph Eubanks. Used with the permission of Timber Press.

W. Ralph Eubanks

W. Ralph Eubanks is a faculty fellow and writer in residence at the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi. He is the author of A Place Like Mississippi: A Journey Through a Real and Imagined Literary Landscape, as well as 2 other works of nonfiction, Ever Is a Long Time and The House at the End of the Road. He is a writer and an essayist whose work focuses on race, identity, and the American South, and his writing has appeared in Vanity Fair, the American Scholar, the Georgia Review, and the New Yorker. He is a 2007 Guggenheim fellow, a 2021-2022 Harvard Radcliffe Institute fellow, and the recipient of a 2023 Mississippi Governor’s Arts Award for excellence in literature and in recognition of his role as a cultural ambassador for the state of Mississippi.