Duane Allman and younger brother Gregg had been raised by their mother in Daytona Beach, Florida, after their father, a World War II veteran, was shot dead in a Christmas 1949 hold-up. The boys had come of age at the ideal time to fall for white rock ’n’ roll, but were intuitive enough to study black rhythm and (especially) blues, and had played in bands together, both on guitar, since junior high. They recorded a single for Buddy Killen’s Dial label and then, as the paisley-clad Hour Glass, went to California, where they jammed with the likes of Paul Butterfield and Pickett’s former drummer Buddy Miles. Duane experienced a musical epiphany watching Taj Mahal’s slide guitarist Jesse Ed Davis, and he subsequently took an empty Coricidin pill bottle and practiced the technique until he was the best young slide player of his generation.

The Hour Glass secured a deal with Liberty in California, but after two disappointing albums they returned south in April 1968 to self-produce some demos at Fame, where a former bandmate Eddie Hinton was now working. The tapes, engineered by Jimmy Johnson, were rejected by Liberty, and after a handful of southern gigs—at which the group’s self-composed rock songs were interrupted by demands for “Midnight Hour” and “Mustang Sally”—they broke up. Duane Allman followed Hinton in seeking session work at Fame—and Rick Hall put him off. The official (and plausible) reason was that Hall had plenty other guitarists already on the books; the unofficial (and equally plausible) explanation was to do with Duane’s appearance. Allman had scraggly long blonde hair parted in the middle, and sideburns that led to distinctly incongruous moustache. He wore denim jeans, cowboy boots with a dog collar around one ankle, and a leather waist-coast with tassles. “Looked like he hadn’t slept in a week, and was high, and was dirty, and looked like hadn’t had a bath in a week either,” was Marvell Thomas’s first impression.

Jimmy Johnson, however, was not about to let Allman slip out of sight. “He was the most natural talent, the kind of guy had the guitar in his hands eight hours a day. None of us was that dedicated.” Slowly but surely, and not least due to his irrepressibly positive personality, Allman worked his way onto sessions, but his initial contributions at Fame, for Clarence Carter and Laura Lee in September 1968, were relatively minor, as if showing off the full range of his talents would be a dangerous move too early in his employ.

[Wilson] Pickett’s first encounter with Allman was typical of time and type, mistaking him for a “gorgeous blond” upon seeing him in the back of a car. But once they got to working in the studio together, they bonded instantly. Pickett saw and heard in Duane an equally dedicated student of his chosen musical genre, another perfectionist carving his own distinct path, another iconoclast who couldn’t easily be towed into line, and a gregarious, outgoing person who could not be cowed or awed. They shared in common a reputation for being inherently crazy, the types that would fill a room with their presence, and they were able to complement, rather than conflict with, each other.

“I called him Sky Man,” Pickett said, “because he stayed so fucking high all the time.” (Already answering to the name Dog, Allman would combine the two monikers as Skydog.) Pickett recalled one evening in the studio when “everybody (was) acting strange, engineer was all fucked up. I said, ‘We ought to cancel the session tonight.’ Sky Man came in and said, ‘You know what I done, man! I put two pills (of mescaline) in the water tank, baby!’ I said, ‘Wow, you dumb ass, you fucked my session up, man!’ But I loved him, he made it up for it the next day. I mean, he could play!”

Rick Hall ensured that they had plenty of songs to work on, and George Jackson supplied several of them. “Search Your Heart” and “Back In Your Arms” were southern soul ballads of the purest kind, Pickett pleading, preaching, and screaming, backed by sublimely simple accompaniment in each case, from the effortlessly harmonious brass section to the instinctive interplay between Beckett and Thomas. Allman held back on both. Jackson’s “Save Me” picked up the mood considerably, Allman playing off of Johnson much like [Bobby] Womack and [Chips] Moman had before him, coming back at the end to throw in a few lead overdubs. There was also “Mini-Skirt Minnie,” which had first shown up on a Stax subsidiary under a different title before being rewritten by Steve Cropper and sung by Sir Mack Rice (newly signed to the Memphis label). Jackson had now added to the song, and recorded a demo version for Pickett in which his own impressive voice fought tooth and nail for dominance with Allman’s piercing solos. On Pickett’s rendition the rhythm section hit on a yet more relentless boogie—but although Allman can be heard playing the main riff while Johnson chugs along beneath him, the solos are curiously absent. Those who never heard the Jackson demo were ultimately none the wiser, and when “Mini-Skirt Minnie” was justifiably released as a single the following spring it duly scored high at R&B, one of the best (and most underrated) of all Pickett soul singles.

Pickett returned to Muscle Shoals for a final session at the end of November. Allman had gained credibility in the interim with a blistering slide guitar solo on Clarence Carter’s rerecording of “The End of the Road”—to which Carter had exclaimed, on tape, “I like what I’m listening to!” The solo was additionally notable for its volume, and Allman went out of his way to explain to Hall how modern amplifiers offered greater resonance, how the harmonic convergences created richer textures and phantom notes.

On November 27, while the others broke for lunch, Wilson Pickett, Duane Allman, and Rick Hall were left alone in the studio. Allman hung back with the excuse that he wanted to spare the other musicians the “looks” he invited wherever he went, and let them eat in peace without him. Most likely, having hit it off so well with Pickett, he just wanted his new buddy’s ear to push an idea he had—that Pickett cover the Beatles’ “Hey Jude.”

Allman’s suggestion was not necessarily out of left field. Among R&B acts, both Otis Redding and the Vontastics had covered the Beatles’ “Day Tripper” to considerable success; Little Willie Walker had tackled “Ticket to Ride”; the reconstituted Bar-Kays had recently released an instrumental of “A Hard Day’s Night.” In fact, Allman had played, albeit without distinction, on Arthur Conley’s tepid cover of “Ob- La- Di, Ob- La- Da,” from the Beatles’ recently released eponymous White Album, just a few days earlier. Nascent rock bands were covering soul songs, too: Atlantic’s Vanilla Fudge had just scored with a ponderously slow cover of the Supremes’ “You Keep Me Hanging On.” It was all part of the post-Monterey cross-cultural mood of the times.

Still, Pickett initially recoiled at the thought. It was one thing to sing distinctively in Italian for a European song festival, but it was something else entirely for this particular soul man to cover what Pickett still considered a white pop band. Additionally, “Hey Jude” was a multimillion seller getting relentless airplay, having only just vacated the number one spot after nine consecutive weeks. Pickett and Hall—who objected to Allman’s idea far more stridently—knew that you simply didn’t cover a million-selling single while it was this hot unless you could do it better and bigger. And in the case of the Beatles this was likely impossible.

There was also the matter of its length. “Hey Jude” had famously crammed over seven minutes of music onto one side of a seven-inch single. Much of that time was given over to a repetitive four-bar coda, its sing-along chorus anchored by drums, piano, acoustic guitars, and a brass instrument or two, with Paul McCartney ad-libbing over the top.

The Beatles knew what they were doing with this. The coda began at precisely the three-minute barrier, if pop radio disk jockeys wanted to bring the fader down at that point. But over at the “freeform radio” that had begun operating on the American FM dial, the new breed of air hosts didn’t care about three-minute limitations. They preferred the extended and ambitious musical statements of the now dominant Long Player (LP) format. “Hey Jude” worked perfectly in both formats, the first single deliberately designed to do so.

Allman also knew what he was doing. He listened to the arrangement, the coda, the chorus, those brass lines and the ad-libs—and he heard a song suited both for Pickett’s vocal ad-libs and for his own desire to extemporize on guitar.

By the time the others returned from lunch, Pickett had somehow been convinced, Hall had gone along with it, and the singer was halfway through memorizing the number. The rest of the musicians were used to being told what to play upon arrival, and were quite familiar with picking up a song in a matter of minutes. “Hey Jude,” typically sly Beatles chord structures aside, was no great shakes. The tape was soon rolling.

McCartney had led the Beatles’ recording with his own voice and piano, delaying the entry of the others until the second verse; at Fame, the keys, bass, and drums of Thomas, Jemmott, and Hawkins opened proceedings in simple unison. “There was no reason for flash in that song, none,” said Thomas. “Just because you have Bachian technique doesn’t mean you have to use it every five minutes.” This unfussy foundation gave Allman the breathing space to introduce Pickett’s voice with a bluesy emulation of McCartney’s piano phrasing, and to then respond to the singer’s every line with a soulful lick. As in the original, the Fame arrangement then picked up energy as the song progressed, until they reached that three-minute mark.

Allman was unusual among contemporary session guitarists in that he played his instrument, a Fender Stratocaster, standing up, as if on stage. Pickett would have it no other way for his own part—and the moment they hit the coda, Pickett unleashed a primal scream that led into a high-pitched holler and the two locked into a musical communication that took on a life-force of its own.

“He stood right in front of me, as though he was playing every note I was singing,” Pickett recalled with enthusiasm just four months later. “And he was watching me as I sang, and as I screamed, he was screaming with his guitar.” Almost a half-century later, Jimmy Johnson seemed no less astounded than he was at the time. “You know what happened there?” he asked. “We don’t know! Something happened. We only did that vamp one time, and we couldn’t stop. We just let it go, and kept going and going and going.”

Quite how long they kept it going is uncertain; the final mix faded out just after four minutes. But for as long as Pickett and Allman traded off each other, it was Rick Hall’s unenviable task to keep the volume unit meters from peaking. His job was rendered none the easier by the fact that everyone was playing live, brass section included. Though a perfectionist readily given to multiple takes, Hall knew he couldn’t possibly call for another run-through on this occasion: what was taking place in the studio was a moment of musical transcendence.

Pickett recalled an instantaneous reaction. “People were going crazy. There’s this one secretary ain’t spoke to me since I been coming down there. All of a sudden she got her arms around my neck.” Jimmy Johnson said, “We realized then that Duane had created southern rock, in that vamp.” It was, indeed, both the lighting of a musical touchstone—and the passing of a musical torch. For if southern rock was born that day at Fame, then southern soul, it could safely be said, would never be quite the same.

At the studio the next morning, with everyone assembled, Rick Hall played a rough mix of “Hey Jude” down the phone line, and in New York [Jerry] Wexler listened along in astonished reverence, asking upon conclusion, “Who’s the guitar player?” (Hall had Allman signed, sealed, and contractually delivered to Fame within days.) Then Wexler pulled his promotions team off of “A Man and a Half,” even though it was just about to enter the R&B Top 40, where it would reside throughout December regardless. The tape of “Hey Jude” (with “Search Your Heart” as the B-side) was expressed up to New York, where Tom Dowd brought in the Sweet Inspirations to add backing vocals. But given the frenetic interplay between Pickett and Allman on the coda, and allowing for the additional heady presence of the brass section, Dowd had trouble shoe-horning them in, and the “na-na-na-nas” that were the bedrock of the Beatles’ coda were only to be heard, low in the mix, for the final few seconds. Pickett’s “Hey Jude” was then quickly handed off to radio, where it took up residency on the rock radio airwaves just as the Beatles’ version was waning; crucially, it proved no less popular at black stations. The single was in the shops by Christmas and entered the charts the week after.

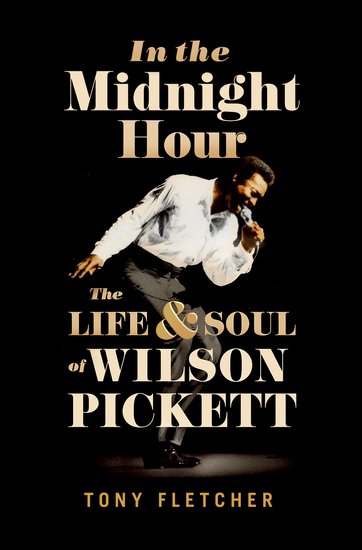

Reprinted from IN THE MIDNIGHT HOUR: The Life & Soul of Wilson Pickett with permission from Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2017 by Tony Fletcher.