In the Hour of War: Carolyn Forché and Ilya Kaminsky on Contemporary Ukrainian Poetry

“Take only what is most important. Take the letters. / Take only what you can carry.”

Our anthology, In the Hour of War, begins: Letters of the alphabet go to war and ends with I am writing / and all my people are writing. It includes poets whose work is known to thousands of people and who are translated into dozens of languages, as well as those who are relatively unknown in the West. It includes writing by former Soviet dissidents and those born well after Perestroika began, and who have grown up in independent Ukraine.

It includes soldier poets, rock-star poets, poets who write in more than one language, poets whose hometowns have been bombed and who have escaped to the West, poets who stayed in their hometowns despite bombardments, poets who have spoken to parliaments and on TV, poets who refused to give interviews, poets who said that metaphors don’t work in wartime and poets whose metaphors startle. What they all share is a war-torn country that refuses to step back, a country whose cities are destroyed by the Russian invaders at the very moment the book is going to print.

The war has been going on since 2014, but it wasn’t until the full-scale invasion of February 2022 that the world started paying attention. Or, perhaps, as some of the poets in the anthology state elsewhere, the war began long before 2014 by way of colonial imperial politics, suppression of language cultures, mass hunger, and terror. All of this is a part of the history of the region, which is to say: a part of its literature.

The poems herein are in conversation with other poems and with one another: Ostap Slyvinsky begins a poem with an epigraph from Kateryna Kalytko, Kateryna Kalytko writes a lyric taking an epigraph from Yuri Andrukhovych, and so on. Among these pages, there are also references to Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert, the Jewish poet Paul Celan, who wrote in German, and many others. Although only a few poems are gathered in this short collection, a careful reader will find echoes among them, in their images, their language, and concerns. Silence is also echoing here: silence is a threat, / during silence, do not open / your door—

This is the silence before the explosion, between volleys of rifle fire, the silence of foreboding, of fear and insomnia, and the silence of complicity. The poems were written in the hour of war, in the lyrics of passing through fire, and so they address the immediacy of warfare: landmines, shellfire, rockets and tanks, warships, rifles, missiles and the corpses they leave behind. But they also speak of the solitude of plants and trees, the breath of those you share life with, the small shudder of a wet twig.

What becomes of ordinary life in times of war? According to the poets, people continue as best they can.

With the exception of Oleh Lysheha, all works in In the Hour of War are by living poets who have, in one way or another, experienced the war. While Lysheha, along with such authors as Andrukhovych, Zabuzhko, Bilotserkivets, and Neborak, are represented here by their earlier lyrics, in part because their work was so formative for the generations of poets that followed them, many others are represented by their new poems. Numerous poems here have been written in the past six months of this full-scale invasion. Thus the poet from Bucha who had to escape his hometown, Lesyk Panasiuk writes:

A Ukrainian word

is ambushed: Through the broken window of

the letter д other countries watch how the letter i

loses its head, how the roof of the letter M

falls through.

The language in a time of war

can’t be understood. Inside this sentence

is a hole—no one wants to die—no one

speaks. By the hospital bed of the letter Й

lies a prosthesis it’s too shy to use.

Meanwhile, staying in Kharkiv, during heavy bombardments, the poet Dmitry Bliznyk writes:

Take immortality, God, but give

me this cold apple cellar. Take the souls

and other toys, but let us live: not-Adam and not-Eve not your son’s—

my son’s life.

Meanwhile, Anastasia Afanasieva, Ukraine’s award-winning poet who had to escape from her native Kharkiv under heavy bombardment by Russian planes, begins her poem in Russian, her native language, and ends it in Ukrainian, an act of defiance, symbolic of how many people in her part of the country feel right now in a time of sentences that are blown by the mines in the avenues, stories / shelled by multiple rocket launches.

This is a poetry marked by a radical confrontation with the evil of genocide: the intentional extermination of one people by another. Does poetry have the tensile strength to embody such a confrontation? There are precedents in the poetry that emerged from the Shoah in 20th-century Europe, and in the aftermath of mass murders in Cambodia and Rwanda: in the voices of Celan, and of the Cambodian poet U Sam Oeur, and the many kwibuka poems written in remembrance of the genocide against the Rwandan Tutsi.

While language is never commensurate with such horrors, it can and does embed a mosaic chip of evidence in the grout of forgetfulness, and challenges attempts to obliterate the truth of history, such as the denial of the Holodomor—the Terror Famine inflicted upon Ukraine by Joseph Stalin in 1932.

In his poem “They Printed in the Medical History,” Boris Khersonsky brilliantly counters the accusation that the deliberate starvation of Ukraine was the stable delusion of a Ukrainian teacher of literature, Anna Mikhailenko, who, for her refusal to be silenced, was incarcerated in a hospital that was at once a madhouse and a prison.

What becomes of ordinary life in times of war? According to the poets, people continue as best they can, but they also carry explosives around the city / in plastic shopping bags and little suitcases. War imposes a certain terrible clarity: show me what you have inside you / pray to the great light / to the rooster perched on a post / to the blind stone and ice-cold water and later, don’t empty wash basins in the dark / halve a raw potato and bury it / all that was all that will be all that calms the heart— / it’s all yours.

These poems provide practical and useful advice regarding how to comport oneself in such a time, and what to pack should sudden flight become necessary. Halyna Kruk, prepared for such an eventuality, confesses that

with each passing day of war

my emergency backpack

has gotten lighter

first I took the food out,

leaving only water

and an energy bar

how much does a person really need

to reach safety

…she asks herself.

Serhiy Zhadan is helpful in this regard: Take only what is most important. Take the letters. / Take only what you can carry. And what is left behind? According to Zhadan, hearths of homes heated by the breath of entire provinces, / the breath of a country. Of those who remain, Kateryna Kalytko, writing in the voice of a soldier on the frontlines, tells us

Life is a house on the side of the road,

old-world style, like our peasant house, divided into two parts

In one, they wash the dead man’s body and weep.

In the other, they dress the bride.

Life and death come into closer proximity, raising the stakes for all concerned, incising the consciousness with excruciating precision, a wound inflicted without the respite of anesthesia, except for a certain war-imposed numbness, described by Ekaterina Derisheva thusly:

a few days in the “war” mode

you turn to stone it seems

no longer fearing artillery fire

the shaking house

you fall asleep to the news

of yet another explosion,

whereupon

houses discuss with each other

where the projectile exploded

and the glass lenses

were blown to shreds.

Late in the 20th century, poems seemed no longer to address or concern the deity, and it is true here too, where according to the poet Andriy Bondar,

the men of my country

prematurely descend into the grave

and become weightless angels

and ideal raw material

for metaphysical speculations

and superfluous argument in favor of the existence

of god or what’s his name.

No certain God appears, but mortality yes, and in defiance Iya Kiva declares: just one step, death, and we’ll eat you for dinner. And what is set in these poems against mortality? Love, of which Yulia Musakovska writes, Like the black grass, birds’ nests turned to ashes and the whisper of the void, / Such love it is which has grown deep into you // and will never let go.

In his poem, “Making Love,” Yurii Izdryk has almost the last word:

this war isn’t war—it’s a chance not to kill anyone

this love isn’t love unto death—it’s as long as it lasts

to protect one another is all this occasion demands.

The word “war” appears dozens of times in this volume yet re-reading it one is struck by the life-giving force of these poems: they witness horror and injustice and yet they call us to honor the world’s need for balm within the language itself, its lyric tilt and courage, the music of defiance and hope.

–Carolyn Forché and Ilya Kaminsky

_________________________________

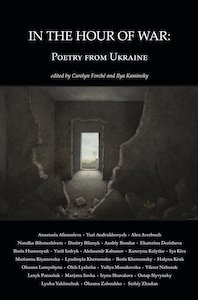

From In the Hour of War: Poetry From Ukraine, available from Arrowsmith Press.

Carolyn Forché and Ilya Kaminsky

Carolyn Forché is an American poet, translator, and memoirist. Her books of poetry are Blue Hour, The Angel of History, The Country Between Us, Gathering the Tribes, and In the Lateness of the World. Her memoir, What You Have Heard Is True, was published by Penguin Press in 2019. In 2013, Forché received the Academy of American Poets Fellowship given for distinguished poetic achievement. In 2017, she became one of the first two poets to receive the Windham-Campbell Prize. She is a University Professor at Georgetown University. She lives in Maryland with her husband, photographer Harry Mattison.

Ilya Kaminsky is the author of the acclaimed poetry collection Deaf Republic, which was called a work of “profound imagination” by The New Yorker and was a finalist for the 2019 National Book Award in Poetry. He is also the author of Dancing In Odessa and Musica Humana. His poems have been translated into numerous languages and his books have been published in Turkey, Holland, Russia, France, Mexico, Macedonia, Romania, Spain, and China. Kaminsky lost most of his hearing at age four after a misdiagnosis of mumps as a cold. In the late 1990s, Kaminsky co-founded Poets For Peace, an organization that sponsors poetry readings in the US and abroad. He currently holds the Bourne Chair in Poetry and is Director of Poetry@Tech at Georgia Tech.