How a 26-Year-Old Steven Spielberg Made Jaws… and Nearly Lost His Career in the Process

Recounting a Chaotic Production (and Mutinous Crew) in Martha’s Vineyard

In late 1973, Spielberg called a meeting to figure out just how on God’s green earth he could make a movie starring a shark. Production designer Joe Alves, an ex-race car driver, had consulted ichthyologists, who said that the biggest great white sharks were, at most, 19 feet long, and untrainable. But the shark in Peter Benchley’s (still-unpublished) novel was a whopping 25 feet—which would require a lifelike mechanical monster that could swim and thrash in the open ocean. Nothing like that had ever been done.

The production team searched for a special effects expert who could help them do the unprecedented. The one person they needed had retired: Bob Mattey, who had been responsible for the giant squid in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Pulled back into service like a movie sheriff, Mattey planned to mount his mechanical shark on a 12-ton submersible platform with a track, requiring a location with a sandy ocean floor, small tides, and an unbroken horizon. In the dead of winter, Alves traveled to Long Island, where Benchley’s novel was set. Nothing looked right. On a whim, he took a ferry to Martha’s Vineyard, which, besides meeting the nautical requirements, had a quaint little village. Perfect.

Benchley’s novel was released in February 1974 and stayed on the best-seller list for 44 weeks. Universal, which had been preoccupied with disaster pictures like Airport 1975, now realized it had momentum to ride, which meant filming Jaws as soon as possible—say, April?

Instead of a year and a half, the shark designers now had a matter of months. Oh, and could they get the picture done before a potential actors’ strike in late June? A panicked Spielberg pushed them off a month. On May 2nd, the Jaws circus descended on Martha’s Vineyard, with a budget of $3.5 million to cover 55 days of filming.

By then, Spielberg at least had a screenplay. Benchley’s initial script had been reworked by playwright Howard Sackler. Unsatisfied, Spielberg sent it to Carl Gottlieb, a writer on The Odd Couple, with the note “Eviscerate it.” Gottlieb sent back a long memo, saying, “If we do our jobs right, people will feel about going in the ocean the way they felt about taking a shower after Psycho.”

Spielberg asked Gottlieb to find himself a role to play, and he chose the corrupt publisher of the local newspaper, a part he himself later cut to near oblivion (and “my heart bled with every cut”). Instead, the town cover-up would be orchestrated by the mayor, who, Gottlieb noted at the time, “bears a passing resemblance to Richard Nixon.”

Charlton Heston had shown interest in the role of the police chief, but Spielberg didn’t want big names. The star was the shark. He cast Roy Scheider, best known for his sidekick role in The French Connection. To play Quint, the Ahab-like shark hunter, producer David Brown suggested Robert Shaw, the burly Englishman from The Sting. As for Hooper, the marine biologist, Spielberg had tried unsuccessfully to get Jon Voight. With days to go before shooting, Gottlieb tracked down his old friend “Ricky.”

At 26, Richard Dreyfuss was a newfangled star after George Lucas’s American Graffiti. He heard about Jaws and told Spielberg, “I’d rather just watch it than shoot it.” Then, after seeing himself in The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, Dreyfuss had a crisis of confidence and reassessed. He met Spielberg and Gottlieb in Boston. Over “drinks and dinner and consciousness-raising,” as Gottlieb delicately put it, they promised to deepen the role. The cast was complete with three days to spare.

The Hollywood crew, in Gottlieb’s words, tumbled into the quaint New England town like “a boisterous 300-pound child.” Alves and his team had built three sharks that could be filmed from different angles, which Spielberg collectively named “Bruce,” after his lawyer. At the hangar in San Fernando Valley where Bruce was built, the designers had gotten the 2,000-pound machines to swim, snarl, gnash, flip their tales, and dive—in a freshwater tank. They hadn’t counted on saltwater corroding the sharks’ insides.

On the Vineyard, Zanuck, Brown, and Sheinberg came to watch a test run. “We had all the executives there,” Alves recalls, “and the thing flipped over. It was embarrassing. It didn’t work.” Spielberg’s friend Brian De Palma, who was visiting as everyone watched the first horrendous rushes, said it was “like a wake.”

“What happened in May and June was just one disaster after another,” production executive Bill Gilmore would recall. “Every single day the shark was put in the water, something went wrong: A hose burst, there would be geysers that would go a hundred feet in the air. The sea-sled shark ran aground.” Stalling, Spielberg shot everything not involving the shark, and they began writing it out of scenes. Gottlieb says, “The decision was: if we don’t absolutely have to see the shark, why make trouble for ourselves?”

For Spielberg, it was an epiphany. “I just went back to Alfred Hitchcock,” he would explain. “What would Alfred Hitchcock do in a situation like this? So, imagining a Hitchcock movie instead of a Godzilla movie, I suddenly got the idea that we can make a lot of hay out of the horizon line and not being able to see your feet, not being able to see anything below the waistline when you’re treading water. What is down there? It’s what we don’t see which is really truly frightening.”

Jaws had become a war zone, with the exhausted crew calling it Flaws. The schedule had long been tossed out. The “panic scenes” on the beach, which required hundreds of splashing locals, were pushed back once it became clear that no one dared go into the cold Nantucket Sound until after the Fourth of July. Jaws author Peter Benchley showed up to play a small role as a television reporter.

The week before, Newsweek had quoted Spielberg saying Benchley’s characters were so unlikable that “you were rooting for the shark to eat the people—in alphabetical order!” Upon his arrival, Benchley stopped for lunch with a reporter, who told him, “Spielberg says your book is a piece of shit.”

Benchley snapped back, “He knows, flatly, zero. He is a 26-year-old who grew up with movies. He has no knowledge of reality but the movies.” With relish, the author added, “Wait and see. Spielberg will one day be known as the greatest second-unit director in America.”

The director had been dreading the day when the scenes on land were done and it was time to shoot on open water. The third act would take two and a half months to shoot, double the budget, and drive everyone to a breaking point. Bruce was still as temperamental a star as Bette Davis. The shark would drag through the water, looking, as Spielberg put it, “like a 26-foot turd.” On good days, they would snatch something usable. On bad days, they got nothing at all. The crew, working out of an overstuffed barge christened the SS Garage Sale, was given a No Beer order, followed by No Card Playing.

Cabin fever ensued. “It was almost mutiny,” Alves says. Things got even worse when the local boat jockeys who had been hired to shuttle equipment went on strike. They resorted to acts of sabotage, like filling the gas tanks of Quint’s fishing vessel, the Orca, with water. The actors started to crack. “Dreyfuss would say, ‘What am I doing on this island? Why am I here? I should be signing autographs in Sardi’s,’” Scheider recalled.

Shaw, who thought Dreyfuss was a “young punk,” goaded him, “Look at you, Dreyfuss. You eat and you drink and you’re fat and you’re sloppy. At your age, it’s criminal. Why, you couldn’t even do ten good pushups!” Pouring himself a drink one day, Shaw remarked, “I would give anything to be able to just stop drinking.” “Okay,” Dreyfuss said—and hurled his glass through a porthole.

When Universal’s Sid Sheinberg visited, he was appalled to see the haphazard attempts to shoot at sea and asked Spielberg if he would consider moving production to a studio tank. “Well, I wanted to shoot this in the ocean for reality,” the young director replied.

“Reality is costing us a lot of money,” Sheinberg said. “If you want to quit now, we will find a way to make our money back. If you want to stay and finish the movie, you can do that.”

“I want to stay and finish the movie,” Spielberg said.

Inwardly, he was panicking. “I thought my career as a filmmaker was over,” Spielberg later admitted. “I heard rumors from back in Hollywood that I would never work again because no one had ever taken a film a hundred days over schedule—let alone a director whose first picture had failed at the box office.” Crew members, Gottlieb reported, would catch Spielberg “sitting morose and alone on the bowsprit of the Orca.”

Out at sea one day, the crew set up a harrowing shot in which the shark rams into the Orca. When Spielberg called “Action,” underwater cables yanked the vessel sideways, causing an eyebolt on its hull to rip out a three-foot-long plank. The Orca was sinking. “She’s going over!” someone bellowed. Radios blared. Frogmen leaped into the ocean to rescue stray equipment, while everyone yelled to save the actors.

“Fuck the actors!” a sound engineer screamed. “Save the sound department!”

On their last night, in September 1974, the delirious filmmakers got into a food fight after Scheider poured a fruit cocktail over the director’s head. The shoot had lasted 159 agonizing days. “I feel like an old man who has been doing this for 20 years,” a weary Spielberg complained. He had heard rumors that the mutinous crew was planning to throw him overboard after the last shot, so he showed up the next morning in leather and suede, hoping it would dissuade them. He checked the final shot through the lens, slipped onto a waiting speedboat, and hightailed it toward land, yelling triumphantly, “I shall not return!”

That night in Boston, he woke up before dawn, palms sweaty and breath short. He caught a morning plane home to Los Angeles. For the next three months, he had nightmares that he was still surrounded by ocean, waiting for the damn shark to work.

_____________________________

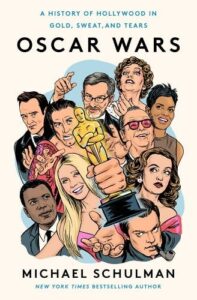

Excerpted from OSCAR WARS by Michael Schulman. Copyright © 2023. Reprinted courtesy of Harper Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.