In the 1960s, the US Decided My Tribe Was No Longer a Nation

Ada Deer on Her Mother's Fight for Menominee Sovereignty

While I was in college and graduate school, a crisis was developing on the Menominee Reservation. In the 1950s the United States moved away from the Indian New Deal of the 1930s, which had been intended to strengthen tribal governments, halt Indian land loss, and revitalize Native cultures. Congress initiated a new policy called “termination,” which sought to end the trust relationship between the tribes and the federal government. Menominees became a prime target for termination. We had rich timber resources that we were utilizing, and a successful claim against the federal government only enhanced our appearance of prosperity.

Policymakers insisted we were prosperous enough to be cut free from federal supervision, but they had little understanding of our economy, the importance of our tribal identity, or the impact termination would have on us. Most Menominees did not fully comprehend termination, but the prospect of such a radical change—abrogating treaty rights, severing ties to the federal government, becoming subject to state and county laws, privatizing our lands and lumber mill—terrified people. My mother attended General Council meetings and kept me apprised as events unfolded. It was very clear that there was trouble at home.

In retrospect, the disaster was not surprising. Although the Menominee tribe was self-supporting and paid the expenses that the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) incurred on the reservation, BIA officials had always exercised a heavy hand, especially where tribal resources were concerned. For decades in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, whites had gotten preferential treatment with regard to cutting, hauling, milling, and marketing our timber.

In 1905 a windstorm blew down trees on large sections of reservation land. In response, the La Follette Act of 1908 mandated that the federal government construct a lumber mill for the Menominees, train Menominees for managerial positions, and institute sustained-yield forestry on the reservation. Although the mill was built, agency superintendents continued discriminatory hiring practices and authorized whites to clear-cut broad swaths of our forest rather than harvesting only mature trees and planting seedlings, as sustained-yield forestry prescribed. Clear-cutting the forests damaged other resources, especially the fish and game on which many Menominees depended for food.

After World War I, agents actively promoted the allotment of tribal land to individuals, a move that almost certainly would have dispossessed and further impoverished the Menominees, just as it had many other tribes. Most of our tribal members did not object to individual ownership of their homesteads, but they wanted to continue to hold our forest in common as a tribe.

In the 1920s, the tribe defeated efforts to allot our land, remove federal oversight, and dissolve tribal government. The tide of federal Indian policy and Menominee governance was about to change, but the pressure on Menominees to embrace individual ownership of what had been common property, adopt capitalist values, and assimilate into the American mainstream did not abate.

The Menominees wrote a constitution in 1924 that placed power firmly in the hands of the General Council in which every adult Menominee had a vote. Four years later, we established the Advisory Council to manage tribal affairs, but its actions remained subject to veto by the General Council. My family was not directly involved in tribal politics: seats on the Advisory Council tended to go to members of a few families who had more education, experience, and money than my Menominee relatives had. Our new tribal government not only continued to reject allotment, but it also sought control of tribal resources and indemnification for federal mismanagement of our forest.

In order to seek compensation, the tribe needed a lawyer, but the tribe’s request to hire one was subject to congressional approval. Finally in 1931 Congress granted us permission to engage legal representation, and in 1935, the year I was born, agreed to permit the Menominees to seek restitution in the U.S. Court of Claims. The claim was based on incidents of mismanagement, such as a BIA agent’s refusal to sell timber blown down in the 1905 windstorm because he thought it would depress the price of white-owned timber. Menominees wanted compensation for those unprincipled acts. It would take 16 years to get it.

In 1934 Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act. This act—designed by Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier and supported by President Franklin D. Roosevelt—was the basis of the Indian New Deal. It ended allotments, encouraged new tribal constitutions that established representative government, and provided for the incorporation of tribes for the management of tribal assets. The Menominees quickly accepted the IRA by a vote of 596 to 15. Then, however, the tribe rejected an IRA constitution that would have enabled them to incorporate.

Because our General Council permitted broader direct participation than the representative council which would have been established under the IRA constitution, Menominees were concerned it might become a tool of the BIA. We also feared that its provisions could make our forest subject to taxation and sale. Menominees have always loved our forest, so we were committed to preserving it intact, stopping federal mismanagement, and ensuring that the timber industry benefited all tribal members. We won a victory in 1934 when Congress gave the Advisory Council a veto over the budget for the lumber mill, a power Menominees repeatedly used to force concessions from the BIA.

Many Menominees would have been quite happy to dispense with federal paternalism and manage our own affairs.

In 1951 the US Court of Claims finally reached a decision that awarded the Menominees $8.5 million, which brought the total amount the tribe had on deposit with the US Treasury to approximately $10 million. Profits from the lumber mill and success before the Court of Claims encouraged a view that had been gaining ground in Washington since the end of World War II: the Menominees should be cut loose and required to fend for themselves as individuals.

The reality was that Menominees were better off than many American Indian tribes because they had resources that, with proper management, could be exploited indefinitely without dependence on outside capital. But their standing vis-à-vis other impoverished Indians reveals little about the economic situation of individuals. Most Menominee families were poor by national and even Wisconsin standards, and tribal resources merely kept the wolf from the door by providing employment, services, and a safety net.

From the perspective of the BIA and Congress, however, we appeared to be a prosperous tribe that no longer required federal services. This view, however, ignored the fact that we reimbursed not only the U.S. government but also the state and county for those services out of income from the mill. When the state agreed in 1949 that Menominees were eligible for subsidies earmarked for the elderly and indigent in Shawano County, for example, the tribe “gifted” the amount disbursed to the county.

Many Menominees would have been quite happy to dispense with federal paternalism and manage our own affairs, but our relationship with the federal government entailed more than services. The United States held Menominee land in trust, which protected tribal assets from sale or seizure. Trust land could not be taxed or mortgaged, and, therefore, federal oversight prevented white timber interests or other entities from acquiring the Menominee forest and lumber mill. The Menominees were strongly committed to the employment of tribal members and to sustainable-yield forestry rather than clear-cutting. Any Menominee man who wanted a job could find one at the mill.

In the 1930s the General Council secured a work schedule at the mill that reflected not only economic hard times but also traditional Menominee subsistence practices. Instead of operating year-round on a shortened workweek to mill the timber allocated for cutting, the General Council approved a plan for ten-hour days until all the logs had been sawn. The mill then closed for the rest of the year so that workers could hunt, fish, and engage in other economic pursuits. As we gained some control over decisions affecting our forest, largely through the Advisory Council’s veto power over the mill budget, Menominees reduced the percentage of the forest harvested annually in order to ensure trees—and the jobs they brought—were always available.

A smaller number of trees taken annually meant that we could cut and mill timber every year. We were determined to favor employment over profits in the management of the forest and the operation of the mill. The BIA did not always endorse such business practices, but Menominees insisted on them. When the tribe won its court claim, the Menominees voted to use some of our money to help alleviate individual poverty on the reservation. “Why should all that money go into the tribal account?” people asked. Since we all owned the forest, we thought, we should each receive a share of the claim award.

Remember that this was our money, not a federal handout, but still we had to get Congress to release it. We decided to seek authorization for a payment of $1,500 to each of our 3,270 tribal members. This would have amounted to approximately one half of the tribal reserve held by the U.S. Treasury. In 1952 a delegation went to Washington to discuss how the tribe planned to spend the money awarded. BIA officials suggested that the per-capita payments might be the first step toward dividing all tribal assets among individual Menominees and relieving the federal government of all responsibility for them. In this proposal, BIA officials reflected changing views on American Indian policy as the major political parties, tired of Depression-era public relief programs, moved to the right.

In the 1952 election Republicans took control of the White House and both houses of Congress. Republicans took a dim view of the New Deal, programs that a Democratic Congress had passed to cope with the Great Depression—and that had enabled the Menominees to gain access to the records on which their legal victory in the claims case rested. The Republicans were not alone in wanting changes, however: the Democratic platform in 1952 also supported revamping Indian affairs.

Among the new Republican members elected to the House of Representatives was our congressman, Melvin Laird. When we asked him to introduce a bill providing for per-capita payments from the award, he agreed, and in 1953 the bill passed the House. But many of Laird’s Republican colleagues saw our request as an opportunity to overhaul Indian policy. When the bill got to the Senate, the chair of the Committee on Indian Affairs, Senator Arthur B. Watkins of Utah, announced that if the Menominees wanted their money, they would have to agree to termination.

In opposition to the New Deal support of Indian tribes and Native cultures, termination sought to end federal supervision, dissolve reservations, and assimilate individual Indians into the American mainstream. Termination involved abolishing tribal governments, allotting tribal land to individuals, removing the protections of trust status, closing the tribal rolls, and divesting of tribal resources. The National Congress of American Indians went on record as vehemently opposed to this policy, but Senator Watkins was firm. To him, the Menominees appeared to be ideal candidates for termination.

Tribal leaders expressed doubts about whether the Menominees would be ready to manage their own affairs, and asked why Congress was in such a hurry.

Compared to most other Indian tribes, we were prosperous. Our forest and lumber mill had enabled us to support tribal services and build up a financial reserve, which our recent court award had increased substantially. Policymakers failed to understand that tribal sovereignty—the right to govern ourselves—underlay Menominee success. Menominees did not approach management of our forests, labor force, or profits in the same way as private enterprise would. We cut trees selectively so that our forest could renew itself. Our mill employed all Menominee men who needed jobs instead of embracing cost-saving techniques that replaced workers with machines. And we viewed the money in our tribal account as belonging to all our people.

In June 1953 Senator Watkins met with Menominees on the reservation and flatly told us that the only way we would get our money was to accept termination. He insisted that we should run our own affairs independent of the federal government. According to him, Congress had already decided to terminate us in three years, and we would not receive per-capita payments until after then. Tribal leaders expressed doubts about whether the Menominees would be ready to manage their own affairs, and asked why Congress was in such a hurry. Senator Watkins responded, “We want to get out of the bad job we are doing and we don’t want to get sued again for $8,500,000.” His glib answer did little to reassure the tribe.

Nevertheless, the senator pressed for a Menominee vote on termination. The tally was 169 in favor and 5 opposed, but the vote count did not accurately reflect Menominee views. Only a fraction of the people eligible to vote turned out. Some perhaps could not be bothered to vote, but most followed a time-honored practice of signaling their disapproval by refusing to attend the meeting at all.

Unfamiliar with the concept of termination, some of those who showed up did not fully appreciate what the senator meant by the term, so when they voted, they thought the issue at hand was the per-capita payment, not the dissolution of the reservation and an end to the tribe’s relationship with the federal government. Furthermore, Watkins refused to permit translation of the proceedings into the Menominee language, which some people understood better than English. As a result, even people who voted in favor of termination were not sure what they voted for.

After the senator’s departure, Menominees learned what termination really meant. Some Menominees thought that termination was inevitable but that the time was not right. Others refused to countenance the idea at all. But virtually all Menominees opposed the immediate termination that Senator Watkins demanded. In fact, hundreds of tribal members signed a petition against termination. Tribal officials called another meeting, and those present voted unanimously to give up the settlement the claims court had awarded them if it required termination.

This was an extraordinarily difficult decision. Menominees needed access to their money, but they were willing to suffer rather than surrender their reservation and their tribal sovereignty. Senator Watkins refused to accept the legitimacy of this vote and forged ahead with plans to terminate the Menominees. On the reservation, rumors flew about the senator’s motivations. Some Menominees thought that his Mormon faith predisposed him against the Menominees, who were mostly Catholic and, like me, had resisted Mormon proselytizing. Others charged that he was trying to bribe the Menominees with their own money.

Later, I realized his attack on the Menominees was part of a much larger agenda. Looking for a guinea pig on which to try out his ideas about Indian policy, he focused on us. He saw himself as emancipating the Menominees from the bondage of federal supervision as the first step in a major reform of Indian relations. In keeping with Republican policy in the 1950s, he championed individual initiative and private enterprise, and he thought that trust status inhibited both.

More troubling was his conviction that Menominees—and by implication other Indians—deserved no say in matters crucial to their future. He simply did not care whether or not we opposed termination: our consent to our own termination was not required. And if he managed to terminate the Menominees, he could then restructure Indian policy in such a way as to destroy reservations and tribal sovereignty in general. Indians would legally disappear. I am still appalled at Senator Watkins’s disregard not only for treaty rights and tribal sovereignty but also for fundamental democratic principles.

In August 1953 Congress passed House Concurrent Resolution 108, which announced a new Indian policy to “free” specific Indian tribes from federal supervision. The Menominee made the list along with the Flathead, Klamath, Potawatomi, Turtle Mountain Chippewa, and all Indian tribes in California, Florida, New York, and Texas. Congress subsequently passed Public Law 280, which extended state civil and criminal jurisdiction over Indian reservations in California, Nebraska, Minnesota, Oregon, and Wisconsin.

President Eisenhower signed the law, although he called it “unchristian,” and Eleanor Roosevelt voiced serious misgivings in her “My Day” column. The Menominees requested and received an exemption from PL 280, but the next year the tribe reversed itself and asked an obliging Congress to make Menominees subject to state laws, enforcement, and courts.

In 1954 Congress passed the Menominee Termination Act, which provided for release of our funds as we had requested two years earlier, closed the tribal rolls so that anyone born after the law was signed could not legally be designated Menominee, and mandated that we prepare a plan for ending our status as an Indian tribe by 1958. That meant deciding how to provide schools, health care, social services, and law enforcement; how to pay for those services; and how to manage our tribal assets.

As Menominees began to comprehend the impending loss of their reservation, they became more critical of their leaders.

Termination became a fact of life for the Menominees. Shawano County officials panicked. The county already was providing some services for Indians but “gifts” from the tribe had helped offset the expense. What would happen when the tribe and tribal assets no longer existed? Indians and whites agreed that they needed more time to prepare for this dramatic change. In 1954 the reservation was mostly forest, and the majority of Menominee men—including my father and brother Joe—worked in the lumber mill, which actually consisted of a sawmill, planing mill, and lathe mill, as well as a chipper and kilns. The mill also had hydroelectric and steam power plants. Menominees worked in the mill personnel and sales offices, as well in the general merchandise store that served employees.

Since its construction, the mill had processed 1.5 billion feet of white pine, hemlock, and hardwood logs, yet the 175,000-acre forest promised to support our tribe indefinitely with careful management. The federal government contributed no more to the reservation financially than it did to white communities; income from the mill supported public services just as local taxes financed similar services beyond the reservation boundaries. The mill and forest, however, had a broader economic impact. A number of individually owned businesses in Neopit—including gas stations, restaurants, and a grocery store—catered to employees of the mill.

In Keshena and elsewhere, other establishments, such as “Indian trading posts,” depended on tourists who came to enjoy our river and forest and to buy supposedly Indian-made souvenirs to take home. Private enterprise, therefore, also depended on the health of our tribally owned mill and forest. Few if any in the tribe foresaw the impact of termination on the tribe’s economy beyond release of the funds from the claim settlement. The most immediate result of the Termination Act was the distribution of the per-capita payments. The tribe had requested that the payments due to children go to their parents, but unbeknownst to the Menominees, Congress changed those terms.

The act specified that the Secretary of the Interior should hold the money for minors until they reached the age of 18. My brother Joe and I were old enough to draw our own payments, but our siblings were not. This meant that, since my mother was not entitled to payment, my father’s payment was the only one available to provide for the support of the three children still at home. I planned to use my payment for college expenses. Joe announced that he was going to buy a car.

I warned him: “You’re going to get this car, they’re going to get your money, you’re going to wreck the car, and you’ll have nothing.” That is exactly what happened. He had nothing, but I had my education. Like my parents, most Menominees had greater needs and responsibilities than either of us did. They used the money to clothe their children, repair their houses, and buy things their families needed. A single payment of $1,500 could not lift anyone permanently out of poverty, but it could provide some temporary relief from the deprivation that many Menominees suffered.

The BIA played no role in preparing the tribe for termination, but instead left the Menominees to devise their own plan, which Congress ultimately had to approve. Our leaders had little experience developing policies or programs. Until this time, the BIA had set forth policy, and the Menominee government had largely reacted; that is, the Advisory Council negotiated with the agent on the implementation of BIA policy on the reservation, and the General Council approved or vetoed the actions of the Advisory Council.

Not knowing exactly how to proceed, the Advisory Council appointed a committee and engaged legal counsel to prepare a plan for terminating our status as an Indian tribe. Most of the leaders of the tribe did not want termination, but they believed it was unavoidable. Nevertheless, they stalled, hoping for a reversal in Washington or, at least, an extension of the deadline.

As Menominees began to comprehend the impending loss of their reservation, they became more critical of their leaders. Some tribal members favored overt resistance instead of the delaying tactics of the tribal government. Although she was not a Menominee, my mother was firmly in the resistance camp. I had just finished my freshman year at the University of Wisconsin when Congress passed the Menominee Termination Act, and throughout my college years, she wrote me frequently about termination, insisting that something had to be done to stop it.

She expected me to join the fight. Finally, I had to tell her, “Mom, I am in school. I don’t know much. I’m a student and I have to learn a lot more. Eventually I will be able to help, but not right now.” Ultimately I did join her, though that time was a long way off. Her example, as well as her words, would inspire me.

My mother joined the growing number of Menominees who opposed termination. She wrote Congress, demanding that the act be repealed, and began to organize her women friends in opposition. Tribal authorities learned of her activism, and in 1957 the hospital fired her from her job as a nurse in retaliation. As a result, we suffered financially because my father’s salary was barely adequate, as were the salaries of most of the people who worked in the mill. By the next year, however, she had managed to scrape together $75.

She then hitchhiked to Washington, DC. For six weeks, while living at the YWCA, she made the rounds on Capitol Hill, urging repeal of termination. My mother returned to Wisconsin more determined than ever to stop what she insisted was a violation of Menominee rights and sovereignty. Although her lobbying did not achieve her desired results, she made a memorable impression. More than a decade later, as I lobbied for restoration, people heard my name and did a double take. I responded, “Same family, same cause, different Deer.”

Both delay and resistance seemed like viable tactics in the late 1950s because attitudes about termination appeared to be shifting. Even the BIA began to have serious doubts about the policy, and in 1958 the new BIA commissioner voiced his opposition. Once set in motion, however, BIA policy stayed in motion, and no one in Washington acted to reverse its course. Powerful members of Congress continued to demand termination, and the president paid little attention to Indians, even after the White House changed administrations in 1961 upon the election of John F. Kennedy.

The Menominees did manage to get the deadline for termination extended to 1961. In the meantime, most Menominees lost confidence in the Advisory Council, which seemed unable to come up with a termination plan. This failure meant that the secretary of the interior could step into the breach and appoint a trustee to implement termination.

In desperation, the Advisory Council created a special committee to devise a plan and named as its chair George Kenote, a Menominee who had worked for the BIA on other reservations for years. I remember him as a handsome, well-dressed man who lived in a nice house near Keshena Falls and whose daughters were acquaintances of mine. I formed no particular opinion of him at the time. Even after I became actively involved in the struggle for restoration, which he opposed, I did not personalize my opposition to his political views. Other Menominees (and my mother), however, did. Political factionalism often became personal during this period, further dividing and demoralizing Menominees.

Support for the termination policy gradually dwindled and proposed solutions to the problems it created produced new divisions.

The debates that ensued were bitter, pitting Menominees against one another. People talk about factionalism among Indian tribes, but factionalism is simply one of the ways democracy works. People sometimes don’t agree about what course their nation should take. Lots of factors shape their positions—personal experiences, race, ethnicity, class, religion, and education, along with self-interest, altruism, and other motivations. This generalization certainly applies to the Menominees, who are not a homogenous tribe.

Almost all Menominees have some European ancestry, but a 1934 congressional act had imposed a “blood quantum” of one-quarter for sharing in an award from stumpage fees, a measure many Menominees still resented since it divided some extended families. Within the tribe, however, “mixed-blood” versus “full-blood” usually reflected cultural orientation rather than a precise blood quantum. Other deep-seated differences gave rise to factions. Religion sometimes divided Catholics from followers of Indigenous religions. Menominees who had money or held managerial positions—people my mother called “upper-crusters”—often espoused views that poorer, blue-collar workers generally opposed.

Age, residence, kinship, and a host of other circumstances could shape reactions to particular issues. Nothing quite as serious as termination had confronted anyone on the reservation in a very long time, so it is no wonder that factions arose over the policy and its implementation. However, support for the termination policy gradually dwindled and proposed solutions to the problems it created produced new divisions.

Although my mother was not a tribal member—she called herself a “white-skin”—she had five children who were, and she had spent most of her adult life on the reservation. As a result, she took a central role in the opposition to termination. She began to think, talk, and write about Indians in a way that few people other than scholars and bureaucrats at the time did. In the 1950s, she was arguing that treaties between the Menominees and the United States were agreements reached between two sovereign nations. Neither nation, she insisted, had the right to enact laws doing away with the other.

This was the Cold War era, and she saw such violations as analogous to the Soviet Union’s annexation of previously independent countries in eastern Europe and central Asia. When the BIA pointed out that a majority of Menominees had voted for termination, she called for a new election, which, of course, the BIA denied. She insisted that tribal leaders demand that the BIA respect and enforce US treaties with the Menominees. Constance Wood Deer was a force to be reckoned with!

My mother made her opinions known in letters to the editor in newspapers, especially, the Green Bay Press-Gazette, and at General Council meetings. She did not mince words. In a letter to the governor, published in the Press-Gazette, she referred to those who had advised him on the legality of termination as “educated idiots and intellectual imbeciles” because they did not recognize the tribal sovereignty implicit in treaties. The letters sometimes provoked angry responses from other Menominees and from tribal leaders. One letter signed by “A group of Menominee women who are tired of your meddling” urged her to “stay home and clean up your house and mind your goats.”

My mother had no such intention. She always attended meetings of the General Council as it debated the final plan for termination, and she did not hold her tongue. When the general council limited her speaking time to 15 minutes, her supporters moved to give her more time, but a voice vote defeated them. Most Menominees had no idea what termination would bring, and the response of many to my mother’s warnings was to metaphorically shoot the messenger.

Termination required the resolution of two major issues—how to provide services for Menominees after termination and how to administer the tribe’s assets, in particular, the forest and the mill. Both had serious implications for Wisconsin. In 1955 the state established the Menominee Indian Study Committee, which included tribal members as well as state and local officials, to advise the legislature on how to respond to termination. The committee in turn commissioned the University of Wisconsin to study the impact of the dissolution of the Menominee Reservation and tribal government.

The more the governor and legislature learned, the more alarmed they became about the effects of termination on the state. Because Wisconsin saw itself as an interested party, the committee and the university became involved in fashioning the termination plan in order to protect state interests. Nevertheless, committee members seemed entirely too interested in the tribe’s forest and not interested enough in other issues, such as the implementation of PL 280, which gave the state civil and criminal jurisdiction over the reservation.

Not surprisingly, my mother frequently attended the meetings of the Menominee Indian Study Committee. Menominees Louise Askinette, Gertrude Richmond, and Ernest Neconish often went with her to the meetings in Madison. Mr. Neconish spoke Menominee and one of the women translated. He accused whites of taking Indian land and interfering with Menominee cultural traditions while my mother described termination as a swindle.

She also regularly attacked George Kenote, who supported termination, calling him “George the Terminator” and, rather ironically, questioning his Menominee ancestry. By 1960, however, even Mr. Kenote was circulating petitions asking to delay termination. But there would be no delay and, with no viable alternative, tribal members voted apprehensively for the final plan.

__________________________________

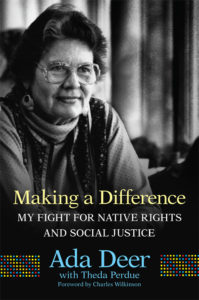

From Making a Difference: My Fight for Native Rights and Social Justice. Used with the permission of the publisher, University of Oklahoma Press. Copyright © 2019 by Ada Deer.

Ada Deer

Ada Deer (Menominee), Distinguished Lecturer Emerita at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, remains an activist for American Indian rights. Ada is a 2019 National Native American Hall of Fame Inductee.