With coffee in hand and puppy at her feet, papermaker Stephanie Hare starts her day in the basement studio of her home. First she’ll take stock of the projects and processes in progress: “I am often working on quite a few different batches of paper or other projects, so I bounce back and forth as time allows.” The whole process takes quite some time, so she typically has fibers in progress at every stage.

If it’s a Kozo cooking day, she’ll be up early, because the process will take close to five hours from start to finish. The raw Kozo—the inner bark of the paper mulberry plant (she prefers a Thai varietal)—has already soaked overnight, and she’ll add those prepped fibers to vats of soda ash and simmer them over propane burners in her tiny backyard in Philly—or at times on her family’s rural property in Maine.

The Kozo will cook in the caustic solution for three hours to break down its tough cellulose and will leave behind a fibrous mush. After a thorough rinse, the mush has to be beaten for several hours to break down the long fibers into a pulp. Hare still does this part without the help of machinery, although she is saving for a mechanical beater that will save time and boost her production. For now, she meditates for a couple of hours while rhythmically beating the fibers with a wooden mallet atop a granite slab. She’ll then hydrate the pulp in a wide vat and add pigment, in preparation for “pulling sheets” (which will result in something that starts to resemble paper).

At this point, the process at SHare Studios would look familiar to papermakers from a thousand years ago. Preceded by papyrus and pressed bark, methods of early “papermaking” coincided with more popular clay tablets. The earliest known true papermaking processes were practiced in China in 100 C.E. Those papermakers also soaked and cooked their mulberry fibers (albeit over wood-fed fires instead of propane burners), and then further softened them to prepare for making smooth sheets.

Over the centuries, this manual process spread from China to Japan, Korea, and other surrounding cultures, and went west into the Middle East and eventually Europe. A major shift in the scale of production came from Islamic papermakers of the eighth century, who refined the process for quality and also increased production by the use of water-powered pulp mills. The importance of and demand for paper drove the papermaking industry further into the West, where it continued to be refined and upscaled. By the Industrial Revolution, pulp was a major industry on its own, and papermaking was dominated by the large companies seen today. Small papermaking ateliers still flourish, but the bulk of the industry has been automated and standardized.

In Philly, Hare moves her hand in a hypnotic vat of indigo pulp-swirled water. This is the part of the process she has always been especially drawn to—the not-quite-paper vat into which she swiftly submerges the deckle (the frame holding a screen, which is known as the mould). She pulls a watery sheet of pulp from the vat and gives it a “papermaker’s shake”—a swift and firm action possibly as unique to each papermaker as their fingerprint. The shake drains the water from the deckle and pushes the fibers to intertwine as the collected pulp spreads evenly to the edges of the mould.

The sheet will sit in the mould and drain while she pulls another sheet (she has multiple moulds to keep the process flowing, and to pull different sizes). Then she flips the drained sheets out of the moulds and presses them between stacks of fabric felts, in the part of the process called “couching.” A hydraulic press flattens the stack of couched sheets to finish removing the water, and also imprints the smooth texture of the felt into the sheets. After that, Hare will either hang the sheets to dry while they’re still stuck to their felts, or transfer them to a “dry box” for a smoother result that is favored by her calligrapher clients.

“There is a sort of reverence that lies at the bottom of the papermaking practice,” says Hare. “I love that it’s a play on the traditional practices that started in ancient China. When you really think about it, paper is one of the most important innovations ever made. It’s interesting to think about how such an important craft could fade away over time to become what it is today.” In many ways, she says, digital has displaced paper, and traditional papermaking has retreated into the realm of arts and crafts. She feels this gives new meaning to what was once such a simple practice. “Handmade paper is truly a unique experience,” she adds. “There is a connection between the maker and the person who inevitably holds the finished sheet in hand.”

It takes hours to cook, pound, and process tough Kozo fibers down to the soft, cloudy pulp that is the most basic and key element for Hare’s work as a papermaker.

Hare’s favorite part of the process is the mesmerizing swirl of the pulp. “The way that the graceful, long Kozo fibers float and slowly churn together, disintegrating and blending into a cloudy abyss still hypnotizes me with every batch,” she says. This is also where she can experiment with color and texture. She currently loves saturated jewel tone pigments like deep blue, forest green, and rich ruby. She’s also been experimenting with adding small feathers, flecks of gold leaf, flower petals, and other plant materials to add texture and pattern, which have stunning effects for the luminaries and lampshades she also makes and sells.

Hare has grown to appreciate her own “papermaker’s shake” as her signature: “By hand-papermaker standards, my shake probably isn’t the best,” she says, but she loves that it’s representative of the way she works, and how it captures the action. “Especially with my longer fibered papers,” she says, “you can see the sort of splash and movement of the fibers as they relax into paper form. I think it adds a lovely depth to the finished sheet, and a sense of motion. I never strive to achieve a perfectly ‘even’ sheet. I much prefer the drama of my signature shake.”

__________________________________

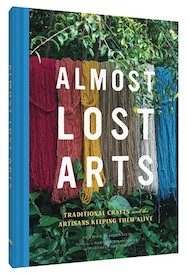

From Almost Lost Arts: Traditional Crafts and the Artisans Keeping Them Alive by Emily Freidenrich, published by Chronicle Books 2019.