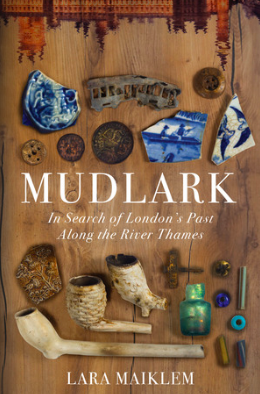

In Search of Treasure in London's

Riverine Mud

Lara Maiklem Goes Mudlarking on the Thames

It is hot and airless on the 7:42 from Greenwich to Cannon Street. I am squeezed between strangers, straining to avoid the feel of unknown bodies. No one makes eye contact and no one speaks. There is an unwritten rule of silence on the early-morning London commute and barely a murmur can be heard, just the rustle of newspapers and the high-pitched squeal of the rails as we lurch and sway towards the city.

I know every inch of this route. For nearly 20 years it has been taking me to the centre of London, for work, to meetings, to see friends and to visit the river in search of treasure. I know when to hold on tight, where the tracks jolt the train to one side, how long the gaps are between stops and when the driver will start to slow down for the next station. For years I have watched old graffiti fade and new graffiti appear. For six months now I have been watching a sports sock, discarded and stuck to the tracks, turn from white to tattered dirty brown.

This journey will take me 17 minutes and I am impatient. I check my watch again and work back three hours from today’s predicted low tide. The river will be at its lowest at 10:23 am. My timing is perfect. I twitch and shift from foot to foot as the train pulls out of London Bridge station, willing it to speed up: I am almost there.

We trundle over a railway viaduct, past Southwark Cathedral with its dappled flint dressing and Gothic spires, and through the centre of Borough Market. I look out over its glazed roof and try to spot the cast-iron pineapples balanced above one of the entrances. Then the sky opens up and I am above the river on Cannon Street Bridge, water flowing towards me from the west and away from me to the east. I scan the river on both sides, peering through the bodies, over newspapers and around rucksacks to check the tide. A patch of slime-covered rubble is just beginning to show through. It is close to the river wall, but the tide is falling. By the time I get down there the river will have dropped even further and enough of the foreshore will be exposed for me to begin my search.

It amazes me how many people don’t realize the river in central London is tidal. I hear them comment on it as they pause at the river wall above me while I am mudlarking below. Even friends who have lived in the city for years are oblivious to the high and low tides that chase each other around the clock, inching forwards every 24 hours, one tide gradually creeping through the day while the other takes the night shift. They have no idea that the height between low and high water at London Bridge varies from fifteen to twenty-two feet or that it takes six hours for the water to come upriver and six and a half for it to flow back out to sea. I am obsessed with the incessant rise and fall of the water.

For years my spare time has been controlled by the river’s ebb and flow, and the consequent covering and uncovering of the foreshore. I know where the river allows me access early and where I can stay for the longest time before I am gently, but firmly, shooed away. I have learned to read the water and catch it as it turns, to recognize the almost imperceptible moment when it stops flowing seawards and the currents churn together briefly as the balance tips and the river is once more pulled inland, the anticipation of the receding water replaced by a sense of loss, like saying goodbye to an old friend after a long-awaited visit.

I have lied, cajoled and manipulated to get time by the river.

Tide tables commit the river’s movements to paper, predict its future and record its past. I use these complex lines of numbers, dates, times and water heights to fill my diary, temptations to weave my life around, but it is the river that decides when I can search it, and tides have no respect for sleep or commitments. I have carefully arranged meetings and appointments according to the tides, and conspired to meet friends near the river so that I can steal down to the foreshore before the water comes in and after it’s flowed out. I’ve kept people waiting, bringing a trail of mud and apologies in my wake; missed the start of many films and even left some early to catch the last few inches of foreshore. I have lied, cajoled and manipulated to get time by the river. It comes knocking at all hours and I obey, forcing myself out of a warm bed, pulling on layers of clothes and padding quietly down the stairs, trying not to wake the sleeping house.

When I first started looking at tide tables, they confused me. I’m not a natural mathematician and numbers just bewilder me, so a page filled with lines and columns of them sent me into a flat spin. But I’ve been studying them for so long now that they’ve become second nature. A quick glance and I can see which tides are good and when it’s worth visiting the river. The most important thing is to choose the correct tide table for the stretch you are planning to visit. There can be a difference of around five hours between low tide at Richmond and low tide at Southend, since the tide falls earlier in the Estuary than it does at the tidal head. Even the length of the low tide varies depending on where you are. While the rise and fall of tides in the open sea are of almost equal duration, 25 bends in the tidal Thames and the dragging effect of the riverbed and its banks shorten the river’s flood tide and lengthen its ebb tide. This means that the river stays at low tide for longer at Hammersmith than it does in the Estuary, which in theory equates to more mudlarking time the higher up the river you go, but even then, depending on the weather and the slope of the foreshore, the river can still catch you out.

I never look at the high-water levels, but I know that a good low tide of 0.5 metres and below will expose a decent amount of foraging space, so I scan the tide tables for these and circle them with a red pen. Spring tides mark the highest and lowest tides of the month. The name comes from the idea of the tide “springing forth” and not, as some mistakenly think, the time of year when they occur. There are two spring tides every month, during full and new moons, when the earth, sun and moon are in alignment and the gravitational pull on the oceans is greater, but the very best spring tides are after the equinoxes in March and September when they can fall into negative figures. They are known as negative tides because they fall below the zero mark, which is set by the average level of low tide at a specific place. A few years ago there was a run of freak low tides that were lower than most mudlarks could remember. Those were the best tides I’ve ever seen. They revealed stretches of the foreshore that hadn’t been mudlarked for over a decade and uncovered countless treasures.

It is the tides that make mudlarking in London so unique. For just a few hours each day, the river gives us access to its contents, which shift and change as the water ebbs and flows, to reveal the story of a city, its people and their relationship with a natural force. If the Seine in Paris were tidal it would no doubt provide a similar bounty and satisfy an army of Parisian mudlarks; when the non-tidal Amstel River in Amsterdam was recently drained to make way for a new train line, archaeologists recorded almost 700,000 objects, of just the sort we find in the Thames: buttons that burst off waistcoats long ago, rings that slipped from fingers, buckles that are all that’s left of a shoe—the personal possessions of ordinary people, each small piece a key to another world and a direct link to long-forgotten lives. As I have discovered, it is often the tiniest of objects that tell the greatest stories.

*

There isn’t much to draw the average mudlark west, and I had been mudlarking for more than a decade before I decided to make a pilgrimage to Teddington. But it makes sense to begin our journey where the tidal Thames starts (or ends, depending which way you imagine the water flowing). The stretch of river between Richmond and Teddington is unusual in that the water levels are controlled. The lock at Teddington artificially ends the tidal Thames, which would otherwise continue further upstream—something in effect it still does when there’s a very high tide and the water overflows the lock. But the tide hasn’t always turned this far west. In the first century AD, it turned where the Romans built their bridge, near to where London Bridge is today.

The demolition of Old London Bridge in 1831 also had an effect on the tidal head. For centuries its narrow arches and wide pier bases had blocked the flow of water and held back enough of the tide to maintain a navigable stretch along the entire tidal Thames, but when it was removed water levels at Teddington dropped by thirty inches and the river was reduced to a mere stream running between mudbanks. Cricket matches were held on the riverbed. On Wednesday June 25, 1884, the Globe reported on a picnic that was held just downstream from Teddington Lock: “‘It has been reserved for this generation to dine where the Thames ought to be … spreading their cloth on the bed of the river and drinking Prosperity to the new lock, which is, or is not to be. That is the question.'” Richmond Weir and Lock was opened in 1894 to counteract this effect and to maintain the water levels between Richmond and Teddington at half tide or above to ensure the river remained navigable.

It is still in use, and every autumn it is left open for about three weeks while the locks and weir at Teddington stay closed, in what is known as the annual Thames Draw Off. This allows the stretch of water between them to rise and fall naturally with the tides, and when the tide is out the water falls so low that vast amounts of riverbed are exposed. For that brief period, it becomes the only part of the tidal Thames where, in places, you can walk from the north (Middlesex) shore to the south (Surrey) shore without getting your feet wet. While the lock is lifted, essential maintenance takes place, environmental surveys can be conducted on the riverbed, local action groups can clear the river of rubbish, and mudlarks can mooch around a unique part of the foreshore.

The best and most fruitful spots to mudlark on the Thames are those where there has been intense human activity over a long period of time and where busy river traffic churns up the foreshore and erodes the compacted mud that contains the river’s treasures. I have never found that much west of Vauxhall, but when I read about the annual draw off, I decided I had to see it for myself. Just once, in any case. It was the photographs that had really captured my attention: pictures of the naked riverbed with stranded boats leaning precariously to one side and people wandering around at will on the dry riverbed. Perhaps the river this far west had something to offer after all.

Draw-off days are always at the end of October and early November when damp mists hang over the water mingling with the smell of burning leaves. During the first week locals descend on the newly exposed riverbed to collect the casual losses and lucky pennies tossed in the previous year. Families pick their way through the shingle and mud, heads down, plastic bags in hand, exploring the newly unfamiliar, wondering at the river’s-eye view. It was this that I had in mind as I began my walk from Richmond Bridge one chilly afternoon in November a few years ago.

I chose to follow the riverside path along the Middlesex side of the river and continue over the bridge, turning hard left down a road that leads to a slipway. From here I joined a tarmac path that was edged with sludgy leaves and gritty mud and set my pace for the long walk to Teddington. I’d worked out my route the night before and knew I had quite a distance to cover, so I’d decided to wear walking boots instead of wellingtons, which are uncomfortable over long distances. I just hoped I wouldn’t need them. The pictures I’d seen didn’t show much mud, but I didn’t want to be walking back with it squelching through the lace holes in my boots as I’ve done after other visits to the foreshore.

Everything was leisurely upstream. I passed a few people, but not many: women pushing buggies with babies bundled up against the cold ambled in contented pairs; joggers apologized as they bounced past. This is the part of the river where people relax and play on the water. There are motorboats, narrowboats and barges turned into houseboats along the banks. In the summer you can hire traditional Thames skiffs here, with old-fashioned names like Linda and Violet painted on the back seat. Even the river is calmer and slower than it is in central London and the Estuary. It lacks the pace and ferocity it acquires as it flows through the city and away to the sea. And to me that is what is missing. But there was no denying it was beautiful.

Willow trees clung to the bank and ancient plane trees lined the other side of the path. There was a scent of earth, rotting leaves and river mud, and birds were everywhere. A group of ducks were sitting fluffed up and huddled on some steps that led to the river and two Canada geese eyed me warily from the bank nearby. Gulls and cormorants flew past, a reminder that I was just over 60 miles from the pier at Southend-on-Sea. Blackbirds rustled in the bushes beside the path and for a time a robin kept pace with me, reappearing now and then and fixing me with his bead-like eye. My great-aunt once told me that robins are the souls of the departed: this is why they come so close and their company feels so intimate. They are the people you once knew visiting from beyond, coming to say hello, and I always say hello back because you never know who they might be. Perhaps my great-aunt herself.

Only the regular roar of planes descending into Heathrow Airport reminded me that I was still in London. But if I ignored that, I could very well have been walking along a country lane back near the farm where I grew up in the 1970s and 80s: 300 acres of heavy Weald clay, 120 milking cows, a collection of old barns and a lopsided farmhouse built in the reign of Henry VIII, all nestled in a green valley at the end of a long concrete road.

A small river ran through the farm and skirted the back of the house, a large ash tree shading its water in the summer and a single willow reaching into its shallows. With my two much older brothers away at boarding school and in the absence of neighbors, the farm dog and the river were my playmates. While the dog chased ducks and swam around in circles, I spent hours fishing with nets tied to long bamboo canes for the tiny fish and water snails that sheltered in the weeds near the bank. I lay in the long grass and watched dragonflies dart and hover among the reeds, dipping their tails into the water to lay their eggs. If I stayed still long enough, I saw water voles emerge from their riverbank burrows at dusk and very occasionally a grass snake twisting silently through the water, its tiny head held proud, forked tongue flicking.

The river flowed from east to west through the middle of the farm and I knew every inch of it: the bends that caught rubbish, sometimes a football and once even an escaped battered rowing boat. I knew the deep bits to avoid and where it was shallow enough to wade across from one side to the other without flooding my wellington boots. I knew where the sticklebacks hid in the weeds, where ducks nested, and how to get into the low space under the concrete bridge where I listened to our cows patiently shuffling back to pasture after being milked. I learned to love rivers on the farm and they have proved to be my most enduring passion.

There are no walls or barriers on the river path at Teddington. For much of my route the riverbank was natural, sloping down to the river at an angle created by the water rather than by man, and the river was right next to me. If I had wanted, I could have stepped off the path, crossed a few feet of dead weeds and grass and dropped right into the water. The brittle stems of dead nettles pushed through the yellowing grass and every so often I passed a wide short set of concrete steps set into the bank. Rowing clubs have their clubhouses along this stretch and I assumed this was where they launched their boats.

I passed an eyot, otherwise known as an “ait” from the Old English īgeth, based on īeg meaning ‘island’. This is Glover’s Island, named after a waterman called Joseph Glover who paid £70 (around £4,400 in today’s money) for it in 1872 and caused a scandal by putting it up for sale twenty-three years later for £5,000 (around £410,000). It was eventually sold in 1900 for an undisclosed sum to a local resident and gifted to the council. It is one of three eyots between Richmond Bridge and Teddington Lock and one of nine on the upper reaches of the tidal Thames. Eyots characterise this part of the river. These mudbanks and slices of land have been carved away from the mainland, deposited by the river and sculpted into long blunt strips and teardrops by the flow of the water. Most of them are uninhabited, wild and overgrown, covered with dense scrub and willow trees that reach down into the water to dabble in the currents.

The opposite bank seemed even more rural and I wondered if I should have taken that route. The houses had gone and there were green open spaces, parks and woodland. According to the map on my phone I should have been able to see the flat scrubby expanse of flood meadows at Ham Lands quite soon, a 178-acre nature reserve that lies in a bend in the river on the south side between Richmond and Kingston, somewhere safe for the river to go if it swells and breaks its banks.

People living along the river at the tidal head are used to the river flooding on high spring tides. There are no river walls or embankments to protect them from these natural forces and the river overflows quite regularly. The houses along the river path at Strand-on-the-Green in Chiswick are well prepared with garden walls and Perspex or glass barriers in front of the windows. Sandbags are at the ready and the wooden planks that slide in to block the doors are on standby.

Over the centuries, the doorways of the oldest houses have physically moved up and away from the creeping water. The number of steps up to them has increased and each step has stolen a foot from the height of the door. Some are now little more than three-foot hobbit doors at the top of a flight of steps—incontrovertible proof that water levels are rising. At London Bridge, the tides rise by about three feet every hundred years, as the ice caps melt, London sinks and various other geographical and environmental conditions come into play. The tides today are higher than they have been at any time in history.

The symbol on the stopper was so powerful and forbidden it intrigued me.

The tide had been falling as I’d walked. The closer I got to Teddington, the more the riverbed was exposed. Some boats were already stranded awkwardly, leaning on their keels, and I started to think about getting down onto the foreshore. I reached Eel Pie Island, the most famous of the inhabited eyots, named for the eel pies once sold there. Eel Pie Island splits the river in two. The channel nearest me was almost dry, apart from a few small pools that had been left behind in shallow dips. Ducks circled them, quacking angrily at the human interlopers who were poking around and marveling at the novelty of being able to walk where the Thames should be. I decided to join them and cast around for a suitable place to descend. I didn’t fancy scrambling through the scrub and weeds into mud of unknown depth and consistency, so the wide slipway that led directly to the foreshore from the road was a godsend.

The riverbed was firm, not muddy at all, just a fine layer of silt the consistency of thin custard. There was an even layer of gravel mixed with small, round pea-mussel shells that popped and crunched beneath my boots. It was clean and natural with none of the rubble and urban waste that litters the foreshore in the city. I looked down at the unfamiliar riverbed, my eyes darting between the freshwater mussel shells, which were everywhere. They were just like the ones I used to search for as a child, convinced that one day I’d find a pearl. I never did, but from latent habit I bent down and picked one up to admire the creamy opalescence inside. Just a few yards away, crows flapped down to turn stones, looking for shrimps and other tiny creatures stranded by this rare occurrence. All around me were the carefully constructed cases of what looked like caddis fly larvae; perhaps the crows were eating those too.

I looked hard along the bank and under the footbridge, but all I found was rubbish—an empty duffel bag, two scooters, an old lighter, a shirt, a wellington boot, headphones, a submerged shopping trolley, a car exhaust, a traffic cone, a mobile phone and 14p in change. Near some steps, a bit further along, it was more promising: a few clay pipe stems, to prove you can indeed find them the entire length of the Tideway, and a fair amount of broken glass. I recognized the thick dark brown glass of beer bottles from the late 19th to early 20th century and the aqua-colored shards of old soda water and lemonade bottles. Perhaps they’d fallen out of creaking wicker picnic baskets or slipped from tired happy hands at the end of the day when this part of the Thames was a mecca for day trippers and boating parties. People swarmed here from the railway stations, while steamers brought crowds of noisy cockneys upriver from the East End.

Among the shards of glass I found a green marble, which was in fact the stopper from a Codd bottle. The Codd bottle is one of those brilliant Victorian inventions that you wish would be brought back into general use, although they still have the sense to use them in India and Japan. In 1872 the wonderfully named Hiram Codd patented his solution to the problem of sealing fizzy-drink bottles. The marble in his bottle sat on a glass ‘shelf’ within a specially designed pinched neck. Gas from the fizzy drink created pressure that forced the marble onto a rubber ring in the collar of the bottle, thus forming an effective seal. To pour the drink the marble was pushed back into the bottle using a little plunger or by giving it a swift bash on something, which is said to have given rise to the term ‘codswallop’. If the bottles weren’t smashed by children for their marbles, they were returned to the manufacturer where they could be washed and refilled.

I’ve been told by those old enough to have bought drinks in Codd bottles that the lure of the imprisoned marble proved too great for many children and a lot of bottles got smashed. I must admit, while I’ve found scores of marbles, I’ve only ever found one complete bottle. Over the years, I have amassed quite a variety of different stoppers, from river-worn cut-glass decanter stoppers and large earthenware plugs for hot-water bottles, to pressed-glass HP Sauce bottle stoppers and delicate perfume dabbers. The oldest stopper I have is Roman, from the second to third century AD. It is a large plug of unglazed red clay, shaped like a fat mushroom, which is thought to have originated in the Bay of Naples where it was pushed into the neck of an amphora, perhaps containing olive oil, before it was sent to London. What I like most about it is the faint line that runs just below the top, from once resting on a sealing bung of clay or plant stuff.

Corked and broken bottlenecks have no real value and are overlooked by most people, but they are precious to me. It amazes me that while the rest of the bottle has broken, the neck remains firmly corked, exactly where it was pushed by the last person to pour or drink from it. I have brought home some very old bottlenecks, 17th-century free-blown wine bottles and tiny apothecary bottles. The corks survived while they were wet, but once they dried out, they shrank and slipped out. With the magic gone there was no point in keeping them, so I returned them to the river.

Plenty of mudlarks don’t bother collecting the black vulcanite stoppers that roll around at the water’s edge and nestle among the pebbles and stones either. They are often smoothed and eroded into mere suggestions of their original form, but I’ve also found them perfectly preserved, still tightly screwed into beer bottles, faithfully preserving what’s left of its contents. Unscrewing them is like opening a smelly time capsule, with a hissing rush of air followed by the smell of hundred-year-old beer dregs turned foul and rotten.

Many stoppers were branded with the manufacturer’s trademark and name, and it’s these I look out for; longforgotten breweries and local soft-drink manufacturers with gloriously old-fashioned names like “Bath Row Bottling Co.” and “Style and Winch.” Most come from London or Kent or Essex, but at Teddington I found one from much further away. It was thick with mud when I picked it up and what I saw when I wiped it clean with a swipe of my thumb gave me quite a shock. It was a large swastika with the name St. Austell Brewery around the edge.

The symbol on the stopper was so powerful and forbidden it intrigued me. I was sure it pre-dated the war, but there had to be a story behind it, so I took to the Internet when I got home. I discovered that the St. Austell Brewery in Cornwall, like other companies, including Coca-Cola and Carlsberg, chose the symbol for its original meaning of health and fertility in around 1890, but withdrew their swastika stoppers in the early 1920s when Hitler adopted it as the symbol of the Nazi party. Stuck with a pile of old stock and with materials in short supply the brewery ground off the offending image so that they could use them through the war. At the same time, vulcanite stoppers were produced with a dip in the top to reduce the amount of rubber needed, and the words “War Grade” stamped around the edge. I used to find a lot of them on the foreshore, but I haven’t found one for a while. Perhaps more people are realizing their worth.

Happy with my unusual vulcanite stopper and with another Codd bottle marble for my collection safely stashed in my pocket, I decided it was time to leave. The light was fading and the blackbirds in the bushes were beginning to stutter their evening chink-chink call. I still had a way to walk to Teddington Lock where I wanted to see the obelisk that marks the beginning point of the tidal Thames. So I began to head west again. This time the path took me inland through suburban streets and around the lucky houses that have lawns running right down to the river.

This is where my mother was born. She grew up playing and picnicking along the Thames at Twickenham and her early years were spent here with her grandmother Kate. When my grandfather came out of the army after the war, she moved with her parents to a neat suburban house close to the river at Thames Ditton. My grandparents lived there for years and I grew up playing in their immaculately manicured garden, which they filled with red geraniums and tomatoes year after year. My grandmother was a very fast driver and visits to their house invariably involved a terrifying journey in her maroon Triumph Herald to watch the boats on the river and feed the ducks while we ate the tomatoes and soggy white-bread salmon-paste sandwiches. Heaven.

I looked down into the mud along the edge of the river at the bottom of Radnor Gardens and tried to imagine a four-year-old version of my mother stuck in the mud, crying her eyes out. She and her older brother spent a lot of time wandering around on their own and one day they found themselves in Radnor Gardens, a small public park beside the river. In the deep mud at the water’s edge was a beautiful cricket bat, which my uncle sent her to retrieve. Thankfully, two ladies passing by saw what was happening. They pulled her out, cleaned her up with their handkerchiefs and sent them both off home.

I was not far from my great-grandmother’s house. If I hurried, I could take a peek at it and still get to Teddington Lock before dark. When I found it in the middle of a long straight road, I recognized it straight away. I’d seen an old faded photograph of it in a box of other family pictures. It must have been taken around the mid-1920s because my grandmother is standing outside with a friend and she’s a teenager. She doesn’t look like the person I remember, but her eyes are the same. Eyes don’t lie, and they don’t age either. The house was the same too, a large Victorian villa built of yellow London brick with bay windows. I stared at it, thinking of all the people in my life who’d crossed its threshold, looked out of its windows and lived in its rooms. It was a curious feeling of familiar and unfamiliar.

Like looking at the riverbed at draw off. I know that Kate and my great-grandfather Albert worked as “antique dealers,” and I know that what they did was not always above board. Both had been born in the East End and were determined to pull themselves up in the world, by any means necessary. Albert ran a ring that fixed auction prices and Kate fenced the goods he acquired. My grandmother told me how her parents sold antiques in bulk, furnishing entire rooms in their house at Richmond and then selling everything in one go. She’d often come home from school to find her room empty, everything sold except a mattress on the floor for her to sleep on.

I’d have loved to knock on the door, explained who I was, invited myself in, but there was no time, it was getting dark and they’d probably have thought I was mad anyway. So I walked back to the main road, consumed by thoughts of family, people I never met and those who had gone and who I still missed. Eventually I turned off down a quieter street leading to Teddington Lock, and a thin iron footbridge that took me over the river. I could just about see the full channel of the non-tidal river beyond and once on the south side it was a relatively short walk to the obelisk that has marked the upper reach of the tidal Thames since 1909, the year the Port of London Authority (PLA) came into being and took control of the tidal Thames. As well as marking the start of the PLA’s jurisdiction, it also marks the upper limit of the old Thames Waterman Licence, the lower limit being marked by another obelisk in the Estuary.

The stone at Teddington is at least less underwhelming than its wind-blown sister in the Estuary, which lists slightly landwards and is surrounded by rubbish blown in off the strandline. Someone has made the effort to protect it with iron railings and it is set straight. I always touch the Estuary stone, so I knelt down on the cold flagstones and reached as far as I could through the railings to try to brush my fingers against the base. I’d finally completed the line between the western and eastern ends of the tidal Thames. The box was ticked and I didn’t need to come back this way for a while.

__________________________________

From Mudlark: In Search of London’s Past Along the River Thames by Lara Maiklem. Used with the permission of Liveright. Copyright © 2019 by Lara Maiklem.