In Search of the Perfect Piece of Wood

Callum Robinson Explores a Generational Legacy of Craftsmanship in Scotland

Picture the biggest tree you’ve ever seen, laid on its side and sliced lengthways into boards no thicker than expensive steaks. Every difficult year, every drought and every flood, all the minerals and pigments leached up from the particular spot in which it took root, the rippling shadows of a woodworm’s pinhole excavations, the relentless tension required to hold up those mighty limbs, and the torturous scarred stains from a barbed wire choker oh-so-gradually absorbed.

It’s all there, folded into the heartwood. Centuries of character, as individual as a fingerprint, written in the figure of the grain and revealed by the teeth of the saw. Now, imagine there are hundreds of trees like this. Literally thousands of years of life and history, stacked together hugger-mugger. That they are all around you.

When it comes to sourcing the finest ingredients, perfect in ways that can’t be defined or categorized… there are times when it pays to get your hands dirty.

Climbing out of the Land Rover, the air is heavy with the scent of damp leaves and woodsmoke, the loud metallic tick-tick-ticking of the engine in the early morning mist. Pale birch trees, rhododendron scrub, and walls of crumbling stone fringe the glade, and towering above them, a pair of hulking Scots pines lurk in their own long shadows, guarding the entrance to this hidden place.

We stretch off the long hours on the road, stamping the life back into our feet, then without a word we assemble our kit. We rummage for thick blue marking crayons, clipboards and runic timber lists, we slip tape measures onto our belts. My father pulls on a battered felt hat, tucks a pencil behind his ear, and squelches off into the yard.

Dominating the yard is a ramshackle cluster of post-and-beam sheds; these are the drying sheds, and to reach them we must skirt around several mighty logs. Ash, oak, sycamore, and smooth gray elephantine beech are strewn haphazardly about, each awaiting their turn at the saw. They have such presence, these woodland behemoths. Such irrefutable dinosaur-haunch heft. The fresh ones—those still close to half-filled with water—weigh several tons. I watch as my father runs a hand along the fissured bark of a huge ash log, as another man might caress a dog’s flank. As if to say: Good log.

Beneath their sagging tin roofs, the drying sheds’ walls are clad with slim spruce logs, roughly sawn into planks and spaced a handsbreadth apart. This is to encourage air circulation, critical to the wood’s curing process. Allowed to move freely around the freshly milled timber like this, the relentless Scottish wind will slowly wick away the moisture, a year for every inch of thickness, plus another for luck. In places the walls have been left entirely open to the elements—gaps just wide enough for a tractor’s forks, or a father and son, to enter. So, together, we duck into the gloom.

Inside it is silent and still, and a lingering musky perfume begins to invade our nostrils: earthy, mossy, and barky. The soil underfoot is dry and fine as talcum powder, tamped down flat by countless tiny scurrying feet. This must be how it feels to creep into a fox’s earth or a rabbit’s warren. As we move further into the shed, the smell gets stronger, until it is more than a smell; it is an overpowering presence. As if the forest itself has grabbed me by the lapels and is exhaling deeply into my face. This is because we are surrounded, almost comically outnumbered, by trees.

These days, of course, it is entirely possible to order your timber from some distant faceless sawmill or builders’ merchant. To have it delivered in neat, square-edged packs of uniform planks, sight unseen. Elegant, clean-limbed hardwoods from Europe, prodigious giants from the Pacific Northwest, iron-hard exotics from South America and Africa, and close-grained, slow-growing birch from the fringes of the Arctic Circle. From aspen to zebrawood, purpleheart to ponderosa pine, and a hundred species in between. With a modern crane-armed truck, a skilled delivery driver can actually lift the stuff directly into your workshop. This is far more convenient, simpler, and faster than selecting in person. And because the timber from big suppliers is commercially logged, kiln-dried, treated, and graded, there’s considerably less risk that hidden rot or unexpected color may be lurking inside as well. But just because it’s easier, cheaper, and less chancy…doesn’t necessarily mean it’s better.

Ask any chef worth their salt: Would they rather get that expert nose stuck right in at the fish market before the sun’s even glanced up from the pillow, or unpack the goods from an insulated box? Forage for chanterelles in rain-sodden glades, or peel away the cellophane behind closed doors? There are exceptions, naturally, but they’ll tell you: when it comes to sourcing the finest ingredients, perfect in ways that can’t be defined or categorized, with qualities that must be perceived rather than picked from a catalog, there are times when it pays to get your hands dirty. And Ben’s timberyard, in the far upper reaches of northern Scotland, is a place to get your hands very dirty indeed.

This yard has no sign, no digital footprint, it doesn’t even have a phone. Secreted away at the end of an unmarked track, five winding miles from the nearest village of any size, its name and whereabouts have spread quietly, organically. Whispered on the lips of tree surgeons, furniture makers, wide-eyed woodturners, and canny farmers. For all intents and purposes, it might as well be invisible. And for those of us who do know of it, there’s a very good reason to try and keep it that way. Much of Ben’s stock comes from old-growth hardwoods, some that were many hundreds of years old when they fell. Trees like this are uncommon, protected, not the sort of things that come down every day.

But because the turnover here is slow and the sheds are small, this wood, when it comes, has a habit of piling up—the old being gradually buried beneath the new. Storm-blown, wizened and gnarled, and often very large indeed, these are trees that found root in an unforgiving environment and somehow scratched out a living. Trees, that is to say, of distinctive character. And while they certainly aren’t to everyone’s tastes, as the world grows ever more manicured, to some this individuality is a rare and precious thing.

While they certainly aren’t to everyone’s tastes…to some this individuality is a rare and precious thing.

All around me, in all shapes and sizes and every conceivable cranny, hundreds of the straight, branchless lower trunks of trees are piled twice my height. Where there is no space left to put them, they hang precariously from heavy canvas slings. Each has been sliced lengthways and then carefully reconstructed into stacks of planks that resemble the full log in the round. In this way the even pressure of the boards, spaced with dozens of slim wooden sticks—imaginatively named “stickers”—and tightly lashed together, helps to keep them flat as they slowly air-dry. These are plain, through-and-through or slash-sawn logs. But bound back together again like this, they are known to many as boules.

Boules are monstrous, magnetic objects, and yet there is something fantastically cartoonish about those neatly splayed slices—so like a log in the first moments of an explosion you can almost imagine Wile E. Coyote himself slamming home the detonator’s plunger. But it isn’t simply their appearance that’s enchanting…it’s what might be locked away inside.

What did the world look like when these trees first broke through the soil? How many hard years and epic storms might they have weathered? Who might have climbed in their branches, sheltered beneath their canopies, carved a lover’s name into their living flesh? And how many lives depended on them over the years? For a native oak—part of the weft and weave of the British Isles’ landscape for millennia—this number is all but incalculable. Mammals, birds and bats, butterflies, moths, insects and plants; thousands of species are supported, and over three hundred depend upon the oak for their survival. As Robert Macfarlane has written, weighing an acorn in his palm, “I hold in my hand not a single tree, but a community-to-be, a world-in-waiting.” Think of that.

__________________________________

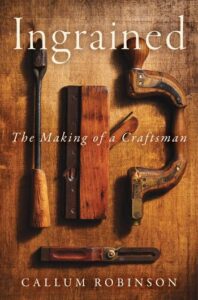

From Ingrained: The Making of a Craftsman by Callum Robinson. Copyright © 2024 by Callum Robinson. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Callum Robinson

Callum Robinson makes all manner of things from all manner of woods for some of the most influential brands in the world. He is creative director at Method Studio, the company he established with his wife, designer and lecturer Marisa Giannasi, almost fifteen years ago. Taught by his father—now one of the UK’s foremost “Master Woodcarvers”—his work has been exhibited widely. He works and writes from a studio and workshop in a forest, beside a loch, nestled in the Scottish hills.