I first saw my father as a pair of feet in Italian leather shoes, bounding down the carpeted staircase of his office building, on one of the oldest streets in Chinatown.

It was a cold, rainy late afternoon in mid- February. When I arrived, only ten minutes before, I had stood at the threshold hesitating, every button on my black peacoat fastened, my breath fogging up the windows flanking the double doors. No one else in my family knew that I was here, or that I was meeting my father for the first time. If they did, they might have stopped me—and I couldn’t risk losing my nerve.

I tried to stay calm and take deep, even breaths.

I had never hidden anything this big from the family who raised me, but I had been waiting my entire life for this moment.

Finally, I pushed the buzzer.

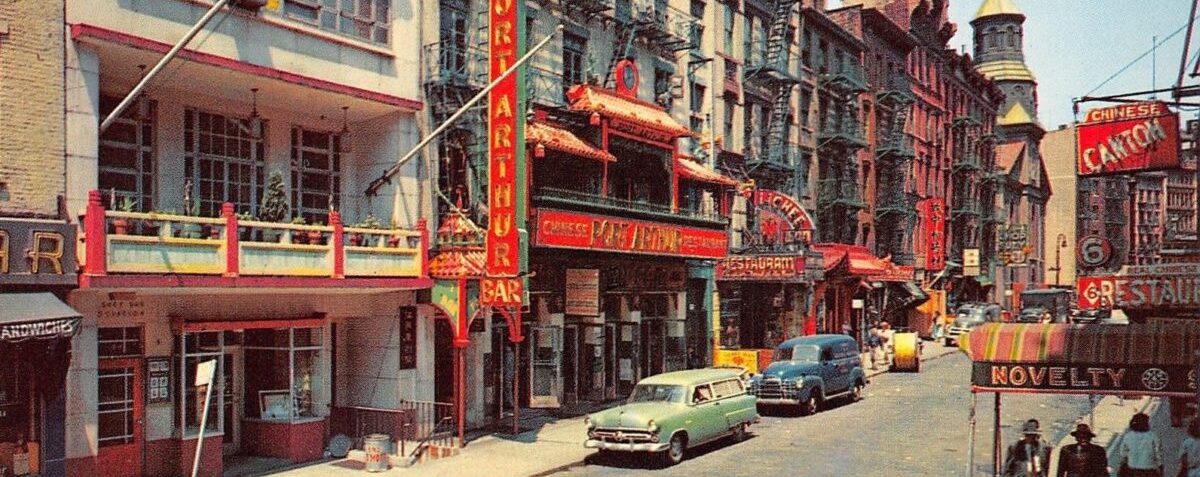

His building, the Edward Mooney House—the only townhouse dating back to the American Revolution in all of Manhattan—was a short two-block jaunt from Mott Street that I had walked numerous times before, as a child on family outings, and later, as a young activist in the community. I had no idea back then that if I looked up to the third floor of this red brick edifice, I could see his office, and perhaps even catch a glimpse of this elusive, mysterious man.

In Flushing, I pined after him—searching for clues in the few objects he had left behind.At the barbershop next door, hairdressers were busy fashioning buzz cuts, flattops, and layer upon layer of Jennifer Aniston Friends-style haircuts. A few doors down, a crowd of tourists was entering the soup dumpling restaurant, the city’s first xiao long bao joint, for dumplings so juicy one had to eat them with both a spoon and chopsticks. Pell Street was a scant two blocks long, but it had everything— TMs, a curio shop, even a Baptist church—though it was so narrow that sometimes trucks had to traverse it with one front and back wheel hiked up on the sidewalk.

I noticed that my father’s name had been outside, on the street-level buzzer that I had just pressed, at eye level, the entire time. As a writer, I liked to think of myself as an observant person, but what other important things had I simply walked past dozens of times, lost in my own head?

Then, finally, I heard the sound of feet running down stairs, and saw those black leather shoes.

Suddenly, the doors were flung open, and a small face with a thin protective smile was carefully peering down at me.

I had the sensation that I was meeting someone very familiar yet very odd—it was rather like being studied from across time and down the long end of a very old, unfolding telescope.

This was my father.

In that moment, as he stared at me, I knew that I had to be perfect, even if it meant that I had to contort myself into someone completely unrecognizable. Someone who spoke softly and reasonably, who wasn’t loud and impossible—an A+ Asian daughter with perfect emotional pitch who wouldn’t scare him with her anger, or give him cause to push her away.

The thought of him rejecting me all over again made the surface of my skin buzz like glass just before the cracks appear.

*

When I was a child, I had recurring visions of meeting him. I imagined my father showing up at my honors ceremony, or any number of graduation convocations—grade school, middle school, high school—waiting there with a bouquet of flowers in the audience, clapping enthusiastically when they announced my name.

In Flushing, I pined after him—searching for clues in the few objects he had left behind. A diamond engagement ring my mother kept for years in a box in her dresser drawer, until she finally hocked it to pay the rent. A stuffed toy koala bear he’d given her in the early days of their courtship, the black paws of which I gnawed at and cut my baby teeth on as a toddler. A gold cross given to me when I was still a newborn by my Chin grandmother, a woman whose name I did not know growing up because the rift between the families was so great that I had never met her.

In other daydreams, inspired by Cecil B. DeMille Technicolor Hollywood films, my father would call for me from his deathbed, like Pharaoh did for Moses. I would rush to him, somehow just managing to make it in time for this, our first and final reunion. In this overblown, gauzy fantasy, despite the fact that my father has other daughters, it is my name that he repeats on his last dying breath.

Sometimes, while taking a bus home from high school, I’d think I’d seen him from the window, a tall thin man walking out of the local pizza parlor, or putting money in the meter for his car—as if I could inherently pick him out of a crowd of strangers, because he was my father and because I supposedly looked just like him.

Was it true? Did I really look like him? Did I really sound like him too, “when I was being obnoxious,” like my mother claimed? (“How is it possible she sounds so much like him when we were the ones who raised her?” my grandmother asked.) I just shrugged and chalked it up to my family’s touchy, but very justifiable anger toward him for walking out.

The only image I had ever seen of my father was a square photograph that my mother produced one day, on a whim when I was in the third grade. I had been told throughout my childhood that I looked just like him, like a Chin, but I did not really know what that meant until that moment.

In the photograph, he was sitting cross-legged, ankle over knee, in my grandparents’ mid-century yellow armchair, smiling for the camera. He had the debonair air of a player—a man with cojones, as the boys in my neighborhood liked to say. His expression and posture emanated such effortlessness, as if such willful virility could barely be contained by the simple boundaries of the photographic record, or apparently, even the responsibilities of fatherhood itself.

I caught a glimpse of the resemblance—the high forehead and cheekbones, the long neck, a propensity for dark circles under the eyes—right before my mother burned the picture with a kitchen match. I lunged at the image, seeking to save it.

The picture vanished in a brief orange blaze and a lingering curl of smoke.

Only my grandmother Rose would talk to me about my father and the Chins.

“You come from a big, big family,” Grandma would sometimes say, usually on a late Friday night, as we sat together in front of the television. We were alone, my grandfather not yet back from his restaurant shift, and nestled together in that same armchair my father had been pictured in before he walked out of the frame. “Too bad they don’t look you up.

It was the first time that I had ever said his name aloud, and it felt vaguely as though I were lying.“Your father was much older than your mother—closer to our age than to hers,” she revealed, as the glare of the television credits scrolled up and down her glasses. “He used your mother, then threw her away.”

Then, sighing, before standing up to get ready for bed. “Oh well. What can you do?”

I always teared up a little whenever Grandma said things like that, not knowing what to do or how to react. Was I to blame? How could I save my mother and myself from the gaping hole he had left?

My father never did show up to any of those graduations and honors ceremonies, no matter how much magical thinking I engaged in, so once I hit my twenties, I did the next best thing— set about stealthily researching my Chin family from afar. If I couldn’t meet Stanley, at least I could start to puzzle together who the rest of my family was. After I graduated from college and became a freelancer at The Village Voice, at the height of the grunge era, I had access to a database. In those last innocent years before the internet, it seemed rather like an oracle.

I plugged in the only search terms I knew—“Chin,” “obituary,” and the year that my Chin grandfather passed away, “1990” (my grandma Rose had seen it in one of the many newspapers she read )—before hitting enter.

Lung Chin, 84, Is Dead; Leader in Chinatown

Section B; Page 10, Column 3; Metropolitan Desk

Lung Chin, a merchant and community leader in Chinatown for more than 60 years, died of cancer on Tuesday at St. Vincent’s Hospital. He was 84 years old and had lived on Mott Street since 1915, several months after emigrating from China. Mr. Chin, a raconteur, was co-manager of two stores, Ying Chong and Sun Yuen Hing. In 1931, he converted Sun Yuen Hing into the Sugar Bowl, the first coffee shop in the neighborhood. . .

Mr. Chin attended Stuyvesant High School and was an alumnus of the Mount Hermon School in Northfield, Mass. He was a longtime leader of Boy Scout Troop 50, a basketball coach for neighborhood youths, a spokesman for the Chinatown Democratic Club and an oral-history contributor to the Chinatown History Project.

Surviving are his wife, Mak Lin; three sons, Stanley, of Manhattan, Stephen, of Tappan, N.Y., and Stewart, of Atlantic City; a daughter, Janice Wong of Southington, Conn. … 15 grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. …

My eye stopped at my father’s name, Stanley. I didn’t know that he was the first son in his family— position of filial privilege. I had so many questions for so many years, and now here was a wealth of information in 205 words that seemed to beg even more questions: Lung Chin? Cancer? Raconteur? (As a slam poet and an activist, I considered myself a bit of a raconteur.) I had 15 first cousins on my father’s side? Stuyvesant and Mount Hermon prep school? Who knew there were Chinese boys in prep school in the 1920s? And then my eye doubled back to his “oral-history” contribution to the “Chinatown History Project,” and the address in Chinatown on Mott Street.

Later that same week, I climbed the magnificent silver wrought-iron staircase of the old Public School 23, where my grandmother and her siblings had attended, which housed the Chinatown History Museum. I had been to the building for rehearsals with a local Asian American dance company, but I hadn’t known that an important family archive was housed steps away. When I arrived at the front desk, an apologetic staffer raised his head. “I’m sorry, but the museum is closed for renovations.”

I just stared at him. The panicky feeling of being shut out—so close to the Chins but so very far away—started to rise up in my chest.

I thrust the obituary printout at him and, in the mad rush of a near-crazy person, said, “I’m looking for my grandfather Lung Chin’s oral history.”

It was the first time that I had ever said his name aloud, and it felt vaguely as though I were lying.

To my relief, the museum staffer’s expression brightened.

“You’re Lung Chin’s granddaughter?” he said, smiling. He jumped up from his seat. “Please, come with me.”

And just like that I followed him into a dark, empty gallery space. Someone would get back to me about the oral history, he informed me, but in the meantime, “There’s something you should see.”

He flipped on the light, and on the far wall was a large, blown-up, photographic portrait of a white-haired man in profile.

Everything seemed to fall away as I walked closer, my footsteps audible against the creaky wooden floors. It slowly dawned on me that I was looking at my grandfather Lung Chin for the very first time.

Lung was lean and elegant, gazing out placidly at something beyond the picture’s frame, chin resting on bony fingers. Under his thinning hair, he had bags under his eyes, just like I had when I didn’t get enough sleep. And there was that very high forehead.

I struggled to hold back the tears welling up in my eyes.

Next to his portrait was another photograph, a rather ragtag picture of Lung and his brothers—tall, formerly athletic, gray-aired men in mid-conversation, sitting on white folding chairs in a backyard in Bradley Beach, New Jersey. I searched for clues of myself in their features, but they were too old and their faces too fuzzy, the photograph blown up larger than its resolution could withstand. The images dated from the mid-1980s, when I was still a teenager, and in the background, a band of blurry school-aged kids, my cousins presumably, and perhaps even my half siblings, were chasing one another.

Looking at the picture of so many generations of Chins at their New Jersey Shore summer home (Chinese on the Jersey Shore?), I felt happiness, pain, anger, relief, and gratitude. Growing up, our family orbit had felt so small—just me, my mother, and my maternal grandparents, and the endless ruminations about my estranged family.

Before I went home, I left my contact information with the staffer, who promised to help me obtain the oral history.

I never received a phone call.

*

One day, a few years later, as I was juggling a magazine career with my creative writing, my mother accidentally ran into my half sister, Stanley’s oldest daughter, at a work conference in Queens.

“Does she ever want to meet him?” my sister asked.

My mother, a former beauty queen, whose anger toward my father only flared out more brightly in the intervening years after he had left, flat-out lied. “No,” she said.

“Of course I want to meet him,” I said, after she had told me about the encounter. “How could you say that?”

Now, some months later, here was Stanley, standing in the ornate, run-down doorframe—tall, good-looking, and distinguished. When he shook my hand, his long, elegant fingers were cold, bony. There was no awkward hug, just an awkward pause.

“Come in, come in,” he said, beckoning me up the stairs.

Then, I was following him, the carpeted steps bouncy under our feet. Even though he was in his early sixties, my father seemed both younger—as a former basketball player, he still had what ballet dancers call “ballon,” that springy lightness on the feet—as well as strangely frail. He had a kind of impish quality that favored sons sometimes have. From the moment he opened the door, I got the sense that if I was not careful he might dissolve into a puff of smoke. (I always had the lingering feeling that I could run my hand right through him like a ghost.)

Stanley had a small side office on an upper floor, which was large enough to accommodate his desk, cabinets, and a chair for clients, along with a side-facing window through which you could see a sliver of Pell Street. Numerous pictures hung on the walls—I couldn’t help but stare at them, one by one, marveling at this life I never had. Family on a row boat on the Jersey Shore.

His oldest daughter from his first marriage, my half sister, wide-eyed and beaming, sitting in our father’s Triumph convertible sports car, the top off. My father with different girlfriends and ex-wives—the singer, the stewardess/ dance partner whom he had married and divorced, twice. Black-and-white photos of him in a cowboy hat, midstride across a platform, one hand extended toward Robert F. Kennedy. A photo of Donald Manes, the disgraced former Queens borough president.

I was trying to take it all in—my father as a tangible reality. I had so many questions: Why was he shaking hands with Bobby Kennedy? Why was Donald Manes, who had killed himself several years before, on his wall? A Triumph sports car?

One of the images that captured my attention was a framed campaign card from when my father ran for state assembly, two years after he walked out on us. It was an outdoor shot, with natural light. He was not looking at the camera, instead focused on something just outside of the frame. His hair was rakishly wavy—plush 1970s hair, parted on one side—and his face framed by a row of stars (“Stanley Chin Assemblyman 62nd Assembly District—Vote Tuesday June 20th”). It was in that moment that I realized my family was right—we did look alike.

What else had I inherited from him?

My father sat back in his swivel chair, the current, older version of himself, and regarded me. He was such the picture of ease that I knew right away it was fake—a false projection, a pretense.

In truth, we were aliens to each other.

He had grown up a firstborn son in a large Chinatown family where my father, as a boy, was the little prince.

He had no clue what it was like to grow up like I had, cut off from an entire side of my family, in a culture that traditionally revered the family as sacred.

I was his daughter, but I was as alien to him as if I had just dropped down from the movable sky.

“So how can I help you?”

_______________________________

From Mott Street: A Chinese American Family’s Story of Exclusion and Homecoming by Ava Chin, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Ava Chin.