In Praise of the Unhappy Happy Ending

Natalie Jenner Breaks Down an Alluring Authorial Move

I always knew why I loved reading happy endings, but it wasn’t until I became a writer that I understood the appeal for their creators: the consolation of leaving one’s characters to a now-uneventful future where nothing too dramatic will ever happen again. But lately in the pandemic, as I reread my favorite novels, I have fallen victim to the allure of something much harder to pin down: the unhappy happy ending.

This is very distinct from the happy happy ending. When I was finishing up my first published novel, The Jane Austen Society, I wrote what I thought was the final chapter, closed my laptop, then missed my characters so much that I went back the next day to give them an epilogue: a catching-up one year later, both for my sake as much as the reader’s. I remember saying to myself as I wrote that epilogue—in one go, in tears, and without ever changing a word afterward—that I wanted to give each of my characters everything their heart desired. So I went for it, and the rush of joy it gave me was like nothing else I have ever experienced. It was like being Santa Claus, God, and Oprah Winfrey all rolled into one!

While promoting the book, I was often asked why Jane Austen peddled in happy endings herself; the disconnect between her satirical eye and the simplistic symmetry of couples lining up has always intrigued us. Austen wasn’t writing her endings due to an uncharacteristic naivete, however: critics have long posited that it was with the discovery of the marriage plot that her tween writerly self saw a way to both extend her writing and bring it to resolution. With my own happy ending behind me, I intuited a much more emotionally powerful reason: Austen loved her characters so much that she wanted to give them the world or, at the very least, the great house, the idealized mate, the long-dreamed-of trip to the sea.

These surface wins for a character, though, reflect only one type of happy ending. Characters—and therefore readers—win when they undergo positive change and show us what is possible in a variety of challenging circumstances, or at least survivable, so that we can derive some measure of hope for our own lives and personal growth. That is why happy endings need not end with happiness.

Unhappy happy endings are, in the end, our real-life middles.

Take Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited and its fairly somber ending (which is also its beginning, given the present-day framework around the plot). To the outside world, narrator Charles Ryder is middle-aged, divorced, and alone, except for comrades in war and his rediscovered faith. But what he really is, is someone who finally sees the truth around him, unobscured by repressed envy. Charles doesn’t get much at the end of the novel, but what he doesn’t do is lose any further. He has reached a new, higher level of emotional understanding and grace, and every time I close the pages to Waugh’s classic novel, I feel the very same.

Another one of my favorite endings is that of The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton. Unlike Charles Ryder, Newland Archer is a man well-situated in society who will always do what is expected of him, even if he suffers the most as a result. Watching Archer rationalize away his happiness with the woman he loves, who is not his wife, is most profound near the end of the novel, when he realizes that his wife was in on the emotional affair all along. Archer’s life has been based on a lie of his own making, and he didn’t even know it.

Perhaps this is why I feel such closure when I reach the final moments of Wharton’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel: In resisting the chance to guiltlessly see his former lover one last time, Archer is, ironically, finally taking ownership of his life and his choices. It’s heart-wrenching all the same, but still a good kind of pain (in a The Way We Were kind of way).

My other favorite unhappy happy ending is that of Kazuo Ishiguro’s masterpiece The Remains of The Day. Butler Stevens has never fully confessed to himself, or to his former colleague Miss Kenton, his longing for her, and he has only begun to wrestle with the fascist sympathies of his late employer Lord Darlington. He remains in the same job he has always held, but now on an estate in reduced social circumstances and saved just in time from the wrecking ball by a rich American.

Yet, by the end of the novel, Stevens will have done three things outside his very narrow comfort zone: taken a vacation, borrowed his boss’s car to do so, and sought out the now-married Miss Kenton under the guise of hoping to rehire her. This is still seismic personal growth for a man who has always lived by the rules of the past and never attended to his needs in the present.

As for Jane Austen, there is one likable and genuine character in her canon whose unhappy happy ending is a little too real for comfort. Charlotte Lucas, the best friend to heroine Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, is the canary in the pre-Industrial coal mine, warning readers of the actual choices facing women at that time without money, prospects or looks. But while Charlotte ends up married not to a prince but a toad, she also gets a home and a child out of it: the happy unhappy happy ending that someone as decent as Charlotte at minimum deserves, and that Austen clearly cannot resist.

It turns out that unhappy happy endings, although far less dramatic, are much more realistic than the happy ending of a double wedding or an outright unhappy one, where someone walks into the ocean in poetic but definitive defeat. Unhappy happy endings are, in the end, our real-life middles. There is something so relatable about a character who only grows—but grows nonetheless—through incremental, minor change. Whose outer life might remain the same, or worse, diminished from what it was. Who perhaps even learns their lessons in life too late.

But the learning is there all the same. George Clooney recently said, “Failure teaches you everything—you learn nothing from success,” and it’s the same with endings. As a shameless romantic, I appreciate when everything works out at the end of a story. But what I love even more is an ending that gives me hope, no matter how middling. Hope that it is never too late to change, that all growth is worthwhile, big or small, and that life will never give up on us, as long as we don’t give up on it.

__________________________________

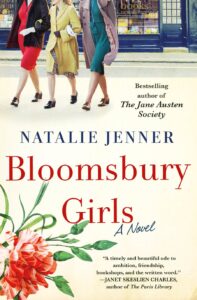

Bloomsbury Girls by Natalie Jenner is available via St. Martin’s Press.

Natalie Jenner

Natalie Jenner is the author of the instant international bestseller The Jane Austen Society and Bloomsbury Girls. A Goodreads Choice Award runner-up for historical fiction and finalist for best debut novel, The Jane Austen Society was a USA Today and #1 national bestseller, and has been sold for translation in twenty countries. Born in England and raised in Canada, Natalie has been a corporate lawyer, career coach and, most recently, an independent bookstore owner in Oakville, Ontario, where she lives with her family and two rescue dogs.