In Praise of the Epistolary Novel

Evan Fallenberg on His Favorite Form of Literary Eavesdropping

In the current world of electronic communication, epistolary looks more like an online weapons outlet than its much tamer true self. Then again, poisoned letters are at the heart of many great works of literature, and letters in general have had the power to upset, alter and even ruin lives, the embodiment of the idea that the pen is mightier than the sword.

Take Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, for example, a hugely influential 18th-century epistolary novel that led not only to spinoffs—literary, musical, artistic—but also to some of the first recorded copycat suicides in history, a spate so virulent that the book was banned in several European countries.

For the most part, however, the influence of epistolary novels is purely literary. And the attractions are obvious: the writer of an epistolary novel has the opportunity to tell a story from a single point of view, two contrasting viewpoints, or many; they can play with the reliability of the narrator(s) while deepening the reader’s reactions of sympathy (or antipathy) without moving to omniscience; and the writer of an epistolary novel often wins over their readers more easily and wholly thanks to the nonfictional feel of letters that may make fiction seem more believable and accessible.

For me there are two added elements that made the style irresistible in the writing of my most recent novel, The Parting Gift: first, there is a stylistic difference between the way we humans narrate a story and the way we write that same story, using turns of phrase we would not use in speech. And of course the way we write—our grammar and syntax and vocabulary—give our personalities away with every word, which is an exciting method of characterization in the writer’s toolbox.

But even more important and more attractive is the manipulation involved in letter-writing, the filtering of events for another reader or readers that naturally takes place. Our interest as readers is piqued when there is some discrepancy between what we know to be true and the letter-writer’s presentation of these facts. Expressed otherwise, it is the dichotomy between how a person perceives herself, what she aims to project to the world, and what the rest of us see: the style of her writing, what she chooses to tell or leave out, the tone. A good writer manages to let that character’s personality present its true self to the reader even when the letter-writer herself wishes to hide parts of her being from the world.

There may be one additional attraction for readers of epistolary novels: while many novels offer a kind of voyeurism, epistolary novels heighten the pleasure of being inside the secret. What, after all, is more naughty and illicit than reading someone else’s letters?

As with the books below—some of my favorites—the varieties of epistolary novels, and thus modes of manipulation, are numerous.

Michael Frayn, The Trick of It

This small novel is a series of one-sided letters written by a literary scholar to a colleague whose letters are an absent presence in the book (the protagonist reacts to them but we never see them), mostly about his obsession with a literary celebrity he eventually marries then nearly ruins, bringing himself to shambles. The treat for the reader is that giddy, nauseous feeling of observing a major disaster in the making; it’s impossible to take one’s eyes off the enormity of the blunder but equally impossible to deny the frisson of delight that creeps up one’s spine.

Marguerite Yourcenar, Alexis

One long letter of explanation and confession from a hapless, departing young husband in 1920s France to his wife, Monique, written in a gorgeous highbrow literary style that deliberately obfuscated the baseness of the matter he is unable to discuss with her bluntly, the reason for his abandonment. The shackles of his imprisonment in his current life rattle through every sentence of this haunting novel, as does the deep regret of hurting the woman he loves—but not enough. The last sentence of Alexis is, in my opinion, the most perfect ending of a novel in literary history.

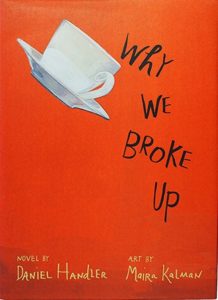

Daniel Handler and Maira Kalman, Why We Broke Up

This book, too, is about the end of a relationship told through a letter (and drawings, and objects). And while it, too, is laced with regret, it also manages to be wistful and funny and sweet. Together, the author and illustrator assemble disparate pieces of the characters and their worlds to make a complete, rich, nuanced whole.

Helene Hanff, 84, Charing Cross Road

Charming. How else to characterize the epistolary communication between two such lovely, subtle, intelligent people? But 84, Charing Cross Road was also, for many, a primer of English society and Anglo-American relations, and, mostly, a bibliography of so much beautiful English literature. Just don’t depress yourself by visiting the site today, unless you are a fan of dark irony.

Alice Walker, The Color Purple

And how many letter-writers have written letters to God? They come in all forms: diaries, slips of paper stuck between the stones of holy walls, etched on stone, prison walls, bits of wood—and of course as novels. What unites them is an intimacy and, often, a desperation, an appeal to someone who will listen when the rest of the world will not, or cannot be trusted. Alice Walker’s groundbreaking 1970 novel gives voice to just such a woman. The letters she sends into the ether are a balm, her only hope of expressing everything in her heart and mind to the people in her life who are just as distant and silent as God.

Lionel Shriver, We Need to Talk About Kevin

Desperation is certainly at the heart of the epistolary communication written by a wife to her husband in the wake of the horrendous crime carried out by their son. But a soul-searching, too, a desire to ferret out the truth, to reach some sort of understanding in the face of the inexplicable. What better method is there than the letter, which offers a pure freedom of unjudged expression, an unleashing of the loop of thoughts in our minds, since no one will read these words unless the letter-writer is willing.

Robin Hemley, Reply All

When I told one friend that I’d written an epistolary novel, he asked “Letters, emails, texts or twitters?” That’s an apt question today, and Robin Hemley’s Reply All answers it beautifully. Though only a short story, it’s got enough drama and great characters for several novels. And humor. The story of a man who mistakenly sends a steamy text to an entire list of colleagues, it’s funny as long as you’re not the one to whom it’s happening. . .

Evan Fallenberg

Evan Fallenberg is the author of three novels and a translator of Hebrew fiction, plays and films. His work has won or been short-listed for numerous awards, including the Edmund White Award for Debut Fiction and the PEN Translation Prize. He teaches at Bar-Ilan University and is faculty co-director of the Vermont College of Fine Arts International MFA in Creative Writing & Literary Translation. He has received residency fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and MacDowell Colony, among others, and is the founder of Arabesque: An Arts and Residency Center in Old Acre. His latest book, The Parting Gift is out now from Other Press.