In Praise of Our Black Women Poets

Arisa White on the Recordings of the San Francisco State Poetry Center

In the Spring of 2016, I received an offer from San Francisco State University to work as a visiting scholar in the Poetry Center on a Black Writers in the Archives curriculum. Creating a curriculum was a tall order for only one semester, considering there are 200-plus recordings, starting as early as the 1950s, of writers who can be classified as black. I began going through the catalogues—some were kept by hand, typed, and written into a ledger; another was nicely printed and bound; and there were Excel spreadsheets for the 90s and 2000s. As I thumbed through the pages, I found my interests pulled toward Alice Walker, Erica Hunt, Harryette Mullen, Ntozake Shange, Rita Dove, Toi Derricotte: the women. I had intellectual and artistic connections with these poets. I broke bread with Walker at her dining room table; I admired the muscle in Hunt’s poems; after my first reading at the Bowery Poetry Club, Bob Holman had recommended Mullen’s Sleeping With the Dictionary; For Colored Girls made up a significant portion of my undergraduate senior conference paper; about Dove I wanted to know more; and Derricotte is the co-founder of my own poetry home, Cave Canem.

Most of the original recordings are organized in what Steve Dickinson calls the Vault—a temperature-controlled room that disintegrating 44mm film leaves smelling like vinegar. There’s bright fluorescent lighting, 7-foot rolling metal shelves full of VHS tapes, cassettes, reels of film, columns of DVDS, and masters and duplicates. I was able to find the original DVD of myself reading with Raina J. Leon on April 9, 2015. Some shelves are still empty, and that space is for the future: for poets who will one day read at The Poetry Center, for the many black female poets who will continue this lineage along. I felt part of something that was regenerative, something that gave my body the security of a back-presence—a posse of poets with the conviction of their word. This allowed me to feel rooted in the now, to feel a greater presence.

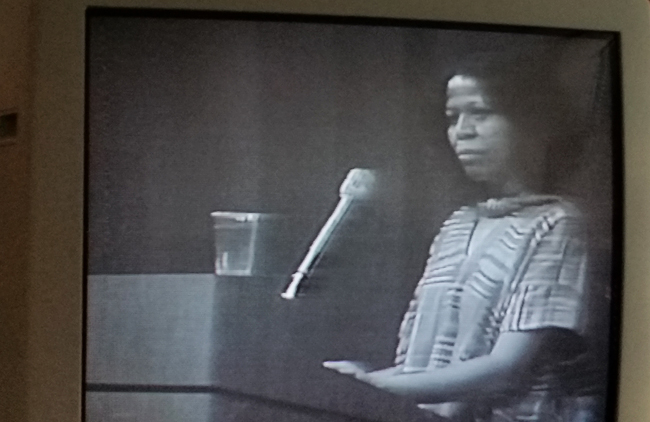

Wanda Coleman

Wanda Coleman

Watching these videos, I entered into a different geological layer within myself. It wasn’t lost on me that the recordings I wanted digitized were from the decades of my birth, childhood, and adolescence. The way these poets occupied space and time was a home-return to rooms that were my own and also part of the grand room of black women poetry. The houses that their poems built offered ways to construct particular experiences and enabled me to have a sense of the future: a future for my poetry.

I pressed play on the VCR and instantly I became sucked in. I snapped photos of the recorded readings like I was a member of the audience. I would clap, too, when the readings ended, and sometimes cry, fully acknowledging that some of those poets were no longer with us. Jayne is gone, Wanda’s gone too, and June passed away in her name. I wanted others to have access to their presence, to know the poem’s primary sounding, the wisdom they’d shared—just seeing how they shaped the space around them would lend a deeper understanding to the architecture of their poems. I decided to focus the digital collection on the black women who had died.

In alphabetical order: Ai, Maya Angelou, Gwendolyn Brooks, Lucille Clifton, Jayne Cortez, Wanda Coleman, Audre Lorde, June Jordan, and Pat Parker.

Clifton’s remark disabused me of the idea that there is something I must erase to make my poetry universal. She freed my mind and body; she freed my verse.

That’s how I started reading poetry too, in alphabetical order in the poetry section of Borders bookstore in the World Trade Center before 9/11. Ai’s name stood out, because the sound was how I heard myself. Sometimes, when writing, I would replace “I” for “A,” because A is for Arisa—my name— and therefore is I. In a 1974 recording from the Archive, Ai reads 12 poems from Cruelty. Suddenly, there I was again, my back pressed against the wooden bookshelves, sitting crossed legged on the industrial carpet, the smell of coffee beans and butter croissants ripe in the air. Ai reads the poems quickly because that was the rhythm in which they came to her, and she requests that the audience keeps their applause to the end. But they can’t help themselves and applaud anyway: I understood them because after listening, I also needed to respond.

When I read Ai’s persona poems in 1996, they split open world after world with truth, with power to dwell in another’s reality. From cover to cover, I fell in love. I wanted to write like her.

Ai passed away on my birthday. I was at Hedgebrook finishing a final draft for what would become A Penny Saved, a collection in the voice of a woman who’s held captive in her home for 12 years. Based on the story of Polly Mitchell, I used reported facts, court documents, transcribed interviews, and my own experience with domestic violence, to write from the emotional terrain of why a woman stays. On the day Ai died, I drank whiskey, celebrating life in the company of writers.

No more than three minutes into a video from April 2, 1987, Lucille Clifton drops this line: “People think a black woman poet cannot be universal.” She retorts by reading her most universal poem, “Homage to My Hips.“ Her words rewired me. Because of those internal voices that echo our social conditioning, what we’re told to be and accept because of our bodies, I could once not believe that black women’s poetry is universal. And because of that belief, I would poet in that manner, using language that complied with those voices, feeling a sense of strangeness about writing my own stories. I was an Other to myself. It’s insidious how deeply we are taught estrangement. But because this archival work allowed me to go back in time, to enter into my own geological layers, I could undo the “nots” embedded there. Without restriction, I learned the capacity of my reach. Clifton’s remark disabused me of the idea that there is something I must erase to make my poetry universal. She freed my mind and body; she freed my verse.

Jayne Cortez

Jayne Cortez

I was most excited to watch Audre Lorde. Lorde was the literary soundtrack to my late teens when I hung out at A Different Light Bookstore in Greenwich Village. Reading her biomythography Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, taught me that I could consciously shape and change reality, and that poetry could be an act of re-visioning, of seeing again and again. I was coming out as a poet: I signed up for the open mics at Brooklyn Moon Café, read for a Mumia Abu Jamal event in the Lower East Side, won a city-wide contest for Women’s History Month. I was going to college for poetry. “So much happens to us,” Audre Lorde says in the recording of her reading from February 7, 1986, at the Women’s Building in San Francisco. It is apparent the toll the bouts of cancer treatments has taken on her. But she is radically self-possessed; her voice, clarity; she is focus and knows her purpose. Lorde continues: “There is so much that happens to us and we’re encouraged so frequently to forget, to lose both pieces of our anger and pieces of our resolve . . . we’re encouraged not to put together the things that happen to us day after day after day. . . . ” She taught me metaphor—that the personal is political and how to see the truth in all things. She reads “For the Record,” dedicated to the memory of Eleanor Bumpers, “Call out the coloreds girls . . . ” and I emerged from her poems knowing what I need to do.

Lorde reminds us, near the conclusion of the video, that “We give our lives to poetry.” This position in the margins gives us a view of who is who and who is driving the bus. Whatever the social impairments placed on me, my sight has the depth of perspective. It is not magical or strong or spiritual—these stereotypes that act as some kind of steroid to get the mind pumped up and keep us from inquiry, from connection. It’s vital to hear her comments, especially when I’m questioning what is the point of my poems, these poems that come out of this black lesbian queer provocateur dandy damie nearly six feet tall woman body. This archival work affirmed my choice to poet, to be a poet, and that there is shit I need to do.

Arisa White

Arisa White is a Cave Canem fellow, an MFA graduate from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, the author of the chapbooks Black Pearl and Post Pardon, the second of which was adapted into an opera, as well as the full-length collections Hurrah’s Nest and A Penny Saved.