In Praise of One of America’s All-Time Great Book Sections (RIP)

Gerald Howard on the Washington Post Book World and the Further Enshittification of All Things

Here is what it felt like to work in publishing, particularly as an editor, from the mid-1970s until the advent of the internet.

You lived, for the most part happily, under a daily avalanche of printed and typed material. You were saturated with words. The manuscripts of course, which arrived as if on a conveyor belt from agents and authors. But also an endless number of periodicals and newspapers, each manifesting in your in-box (in-boxes!) with the implied understanding that you should at least try to read some of its contents. Publishing companies were generous with subscriptions, some of them for you alone, others shared with three or four of your colleagues. The latter would be routed by assistants with initials, and you’d cross off yours once done and send it to the next person.

On and on these publications came (and then went): Publishers Weekly, Kirkus Reviews, Library Journal, Booklist , the Times Book Review, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, New York Review of Books, Saturday Review, The American Scholar, Esquire, Gentleman’s Quarterly, Vanity Fair, The New Republic, People, Harper’s, Atlantic Monthly, The Paris Review, Washington Monthly, it never ended and you really didn’t want it to. Some of the magazines you just skimmed for reviews and book chat, others you read a portion of, and some others you felt an intellectual or literary obligation to pay very close attention to, even if the contents had no connection to anything you were working on. You were expected to keep up, and that was both a requirement of the job and a pleasure. For someone like me this approached perfect happiness. My survival to my current age (75) is proof positive that no number of book reviews read, however high, can possibly have the least ill effect on one’s health, or I’d have left the planet a long time ago.

To put it bluntly, you read the Times Book Review because you had to, but you read Book World because you wanted to.

It was slightly different with newspapers. Everybody read the Times of course—it was the Age of Kakutani—on the subway or at your desk with the morning coffee. Reviews from most of the out-of-town papers mostly arrived courtesy of the clipping service. But the publicity department would have certain key Sunday papers delivered, and you could, and usually would, wander over there on a Monday morning and extract the book sections for perusal. The Los Angeles Times, the Boston Globe, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the Chicago Tribune had excellent book sections, especially the Globe, which could draw on the rich literary and academic resources of its home city.

But the book section you really wanted to get your hands on was the Washington Post Book World, which for reasons I’ll get into shortly was more than the equal of the Times Book Review, not in impact necessarily, but rather in its sheer reading interest and its lack of predictability. To put it bluntly, you read the Times Book Review because you had to, but you read Book World because you wanted to.

The reasons for this state of affairs were complicated and no doubt arguable. Here is my theory: If one of the reviewers for the Book Review seems to get something wrong, or if the selection of a particular reviewer for a book seems misguided or fishy for some possible conflict of interest or a myriad of other reasons, oh the hue and cry that ensues. So the editors need to play it safe in their selection of writers. As for the writers themselves, they are well aware that whatever they have to say about a book, pro or con, in there will be intensely scrutinized, a mindset that can lead to nerves and caution and a certain hedging by all but the most self-confident writers. The publication and its contributors have strong reasons to play it safe, which is not an optimal condition for lively criticism. Or so I have observed over the decades

Book World and its editors and reviewers lived and worked in, well, a safer space. They had the same professional responsibilities, of course, but outside the glare of the Gotham spotlight they felt freer to take chances, be more idiosyncratic and even eccentric in their choices and opinions. And that made for more interesting book coverage overall. The section had other advantages as well.

One of them was geographic: the paper’s hometown location in the nation’s capital meant that the review editors had easy access to the best writers and most starry bylines for coverage of works on politics present and past and also on American and world history. The Washington Post had tremendous glamour (Ben Bradlee, Woodward and Bernstein, Sally Quinn, its dauntless owner Katherine Graham) and clout, and this was a resource the editors and writers in Book World could draw upon for their own purposes. An editor could pick up the phone and try to get a former secretary of state or the treasury, a grandee of the House or Senate, and probably even ex-president or vice-president and pitch them to review a book with a reasonable chance of success. Since, among other considerations, they probably had a book in the works themselves and needed the good opinion of Book World right then or in the future.

Invidious comparisons aside, the plain fact was that Book World was simply very good at what it was meant to do, which was to interest readers in the books publishers were putting out, by way of well-crafted, persuasive and fresh reviews and features.

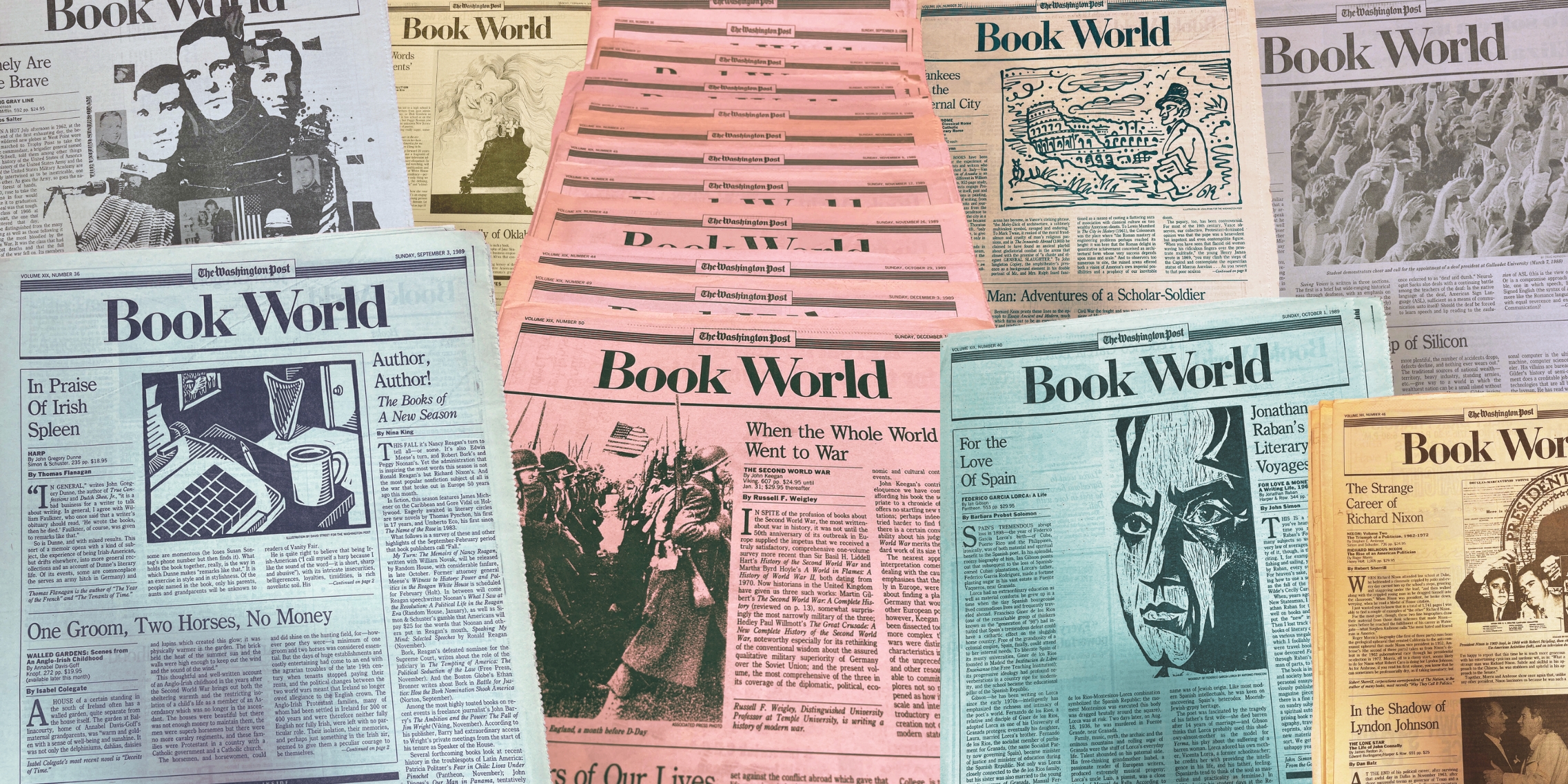

In 2022 the most excellent Michael Dirda, on the occasion—sigh—of Book World’s all-too-short rebirth, wrote an affectionate and informative inside history of the supplement. It became a free-standing Sunday section in 1972 under the editorship of William McPherson who held that post until 1978 and would himself receive a Pulitzer Prize for his literary criticism in 1977. This was just as the Watergate era took hold and the Washington Post was becoming the most important and avidly read paper on earth. Over the years, Book World was blessed by exceptionally able editorial staffing, including three impressive editors-in-chief, Nina King, Brigitte Weeks, and Marie Arana.

There is the bitter irony to consider that this literary erasure was done by the man who owns the largest bookselling entity on earth.

Michael Dirda went on staff as an editor in the spring of 1978 after having written several reviews for McPherson; his remit was to assign reviews for books that were non-political—fiction, poetry, history, and children’s book. This didn’t stop him from becoming one of the publication’s most prolific and enjoyable critics. I never failed to read one of his pieces and I got the sense that he was one of the best-read people on the planet; if he hadn’t already read every book ever published it was just a matter of time.

Dirda had an interesting line in fantasy and science fiction, initiating a monthly column on the genres—which had lacked adequate coverage and respect—that became a must-read in the field. He also assigned reviews to such relative exotics as the novelists Roberston Davies, Gilbert Sorrentino, and Angela Carter, polymath Guy Davenport, composer and diarist Ned Rorem, and classicist Bernard Knox. (Carter, he remembers, expressed something like disdain in her review of Marquez’s otherwise universally praised Love in the Time of Cholera, a review it took some guts to print.) Dirda himself won a well-deserved Pulitzer Prize for his criticism in 1993.

The third of Book World’s Pulitzer Prize winners was the redoubtable and more than a little intimidating Jonathan Yardley. He joined Book World as a regular reviewer in 1981 after a time as a newspaper reporter and then making his bones as a book critic for the Miami Herald. (Happily, Connie Ogle is carrying on the Yardley tradition at that paper.) A man of impressively Stakhanovite productivity, Yardley produced some 3,000 reviews for his employer until retiring in 2014. He was never a particularly stylish writer, he was culturally conservative and sometimes cranky, he was prone to expressions of near-contempt for publishers, but Yardley had that quality, hard to describe but unmistakably present, that important critics had: authority. You had to read him and you had to reckon with what he had to say.

A meat-and-potatoes litterateur, he was very much a Hemingway, Fitzgerald and, especially, Faulkner man, and he was impatient with proto-woke opinion and with what you might call advanced fiction. As uncuddly as he was, I never failed to read a Yardley review and when he liked something I’d published, I felt both blessed and relieved. I miss his irreplaceable voice in the literary conversation. Respect.

In my decades as a book editor, from bright-eyed beginner to graying veteran, I took the existence of the Washington Post Book World for granted, taking immense pleasure and instruction from its pages. Even after the free-standing supplement disappeared, the paper continued to publish some of the smartest and liveliest literary criticism in newspaper journalism.

Looking at you, delightful Ron Charles, who somehow has managed to transform book reviewing into a performative endeavor with no falling-off of seriousness. And you, supersmart Becca Rothfeld. And now they and their colleagues and all that they did are gone, wiped out in a cruel, thoughtless act of oligarchic cultural vandalism. (I have read that the far-flung foreign correspondents of the Washington Post were fired by email without any consideration of how they are meant to be able to pay to get back home. Nice.)

There is the bitter irony to consider that this literary erasure was done by the man who owns the largest bookselling entity on earth. But then Jeff Bezos even back in the early days of Amazon wasn’t really interested in books as such; they just ticked off all the right boxes as objects for retail sale as he planned for planetary conquest. You can see how little they matter to him and his minions when you look at the online bookselling slum that Amazon has become. Well, one person’s cultural tragedy is another, far richer person’s accidental collateral damage.

To use Cory Doctorow’s invaluable term, the enshittification of everything continues apace. But for a moment let’s remember how excellent a run the Washington Post Book World had, and how superb its editors and writers were at their tasks. And if you feel like humming the tune “Camelot” while doing so, go right ahead.

Gerald Howard

Gerald Howard retired from Doubleday as executive editor and vice-president in 2021. His book The Insider: Malcolm Cowley and the Triumph of American Literature was published last year by Penguin Press.