“Born in hell-fire, and baptized in an unspeakable name, Moby-Dick…reads like a great opium dream.”

Raymond Weaver, Cambridge History of American Literature

I’ve finished reading Moby-Dick. Congratulations are welcome, of course, or why else read a classic? Still, I’m worried that, if only for a spell, I am become one of them, a harpoon-carrying member of the Melville cult. This is something like being a James Joyce devotee; there are no soft affections, only unrelenting opinions and admiration. And that’s a bit what I feel with Melville. I love the guy who did Modernism before Modernism thought to Make It New and retread his first steps. I believe in his greatness and will defend his cult/critical status to anyone, which I grant is probably unnecessary given Melville’s established status. The Whale is nonetheless a book I started because it is Important and I Must. Like any great read that isn’t why I finished it. I had approached the text with a similar sense of misguided reverence in high school and thought Melville a boring cetology brochure. The final chase of the actual whale was a sprint, thought my 15-year-old self, following an unendurable marathon of tidbits and trivia and digressions. Rereading 12 years later, however, I find myself agreeing with what a friend said when I first started: the whale chapters are the most important.

A reviewer contemporary with Melville summed up the book as well as one can: Moby-Dick is “two if not three books… rolled into one,” with “Book No. 1… a thorough exhaustive account admirably given of the great Sperm Whale,” “Book No. 2… the romance of Captain Ahab, Queequeg, Tashtego, Pip & Co,” and Book No. 3 “a vein of moralizing, half essay, half rhapsody.” This description fails to capture the tortures Melville imposes upon the English language. His descriptions radiate as from a bomb, are devastations that wreck any effort one makes to capture their energy. Melville packs his epic with so much poetry that stichomancy never seemed so plausible a ritual. Open any page, stick your finger where it will, and discover that “rainbows do not visit the clear air; they only irradiate vapor” or observe “the waves [nodding] their indolent crest.” If the whale and Ahab loom large in the West’s literary landscape, it is chiefly because they are products of prose that is booming, beautiful, fantastical, and as deliberate as a blueprint when necessary.

Indeed, given Moby-Dick’s difficult language and often opaque pacing, people typically fall back on other books of the Western Canon to give it some literary context, citing Milton, Shakespeare, and the Bible. Ahab, to be sure, belongs with Hamlet and Satan in the hall of tortured protagonists. Unfortunately, Shakespeare and Milton aren’t exactly helpful on the subject of whales. If Moby-Dick can be summed up as the three books outlined above, such comparisons might develop our understanding of it as a romance or rhapsodizing essay. But what are we to make of Moby-Dick, sperm whale textbook?

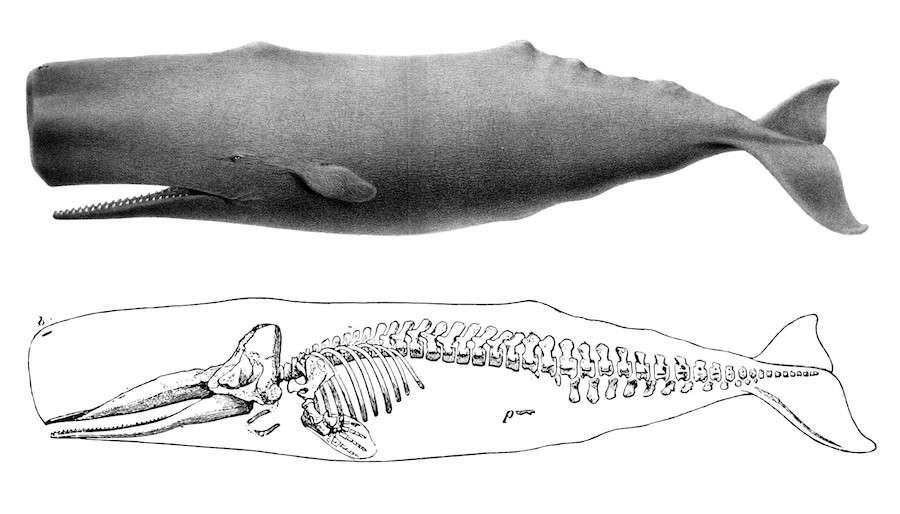

Melville settles this question himself: “The living whale, in his full majesty and significance, is only to be seen at sea in unfathomable waters.” We are dealing with a reclusive monster that Melville means to make plain. And yet a sperm whale made plain is an impossible, frightful proposition that generally happens only to sailors stranded at sea. Melville’s whale chapters are thus a coordinated effort to confront the reader with the reality of his creature, and to thereby engage dueling facets of the reader’s imagination, both the scientific and the poetic. “Other poets,” as the narrator puts it, “have warbled the praises of the soft eye of the antelope, and the lovely plumage of the bird that never alights; less celestial, I celebrate a tail.” By forcing the reader to consider the measurements, facts, and habits of a creature alien in size and habitat, he can build to observations and questions that (he argues) only this specific creature best inspires. Take the sperm whale’s brow, which allows “you [to] feel the Deity and the dread powers more forcibly than in beholding any other object in living nature,” because “you can see no one point precisely” in person. This observation is enforced by Ishmael’s description of each point at length, including the small eyes, hidden ears, and ponderous jaw, so that Melville builds from precision to sublimity. The whale is a picture of nature’s endless mysteries because he is a picture of its endless measurability.

As such, Ishmael’s whales—their catalogued parts and sizes and the stories of their use and myths—do more than prop up the sailor’s mix of romance and drudgery. Melville’s commitment to conveying whaling minutia capsizes the plot every two or three chapters because whaling minutia is the engine behind the story’s motion, a specific terror and fascination in the face not of general Other, but of this Other, one usually unknown and often no better comprehended for being fully examined.

A simple retort to all of this might be, Do we need the whale chapters to convey this specificity and capture the reader? Some years ago, Adam Gopnik thought it possible we didn’t. And maybe we don’t need every bit of every whale chapter, maybe, as Gopnik puts it, “there’s too much digression and sticky stuff and extraneous learning.” This was more than a hypothetical situation for Gopnik, however. He was reviewing an edited version of Moby-Dick that excludes such passages. When finished, he even concludes, “Nice job—what were the missing parts again?” Still, despite this reaction he was unable to escape the original’s pull. Upon returning to it, he determined that “the subtraction does not turn good work into hackwork; it turns a hysterical, half-mad masterpiece into a sound, sane book.”

A sound, sane book is a terrible waste of Melville’s prose and vision. His self-appointed charge is to put the whale to the page, whole and complete. With such a grand design, he is forced to invent language rich enough to erect a project as grand and perhaps unachievable as “the great Cathedral of Cologne.” For the reader, this means we approach the inevitable clash of the book’s final moments suffused with the data and musings and mutterings of whale knowledge that Melville tabulates, indulges, and secretes through the entire narrative. This generates the appropriate response to the white whale’s seeming invulnerability, its incarnation of natural malice, life’s necessary physical hardship, or any and all themes Melville stuffs into his great creature. But most importantly, the suffusion allows for a specific reaction to the whale as whale, which Melville himself is intent upon: “So ignorant are most landsmen of some of the plainest and most palpable wonders of the world, that without some hints touching plain facts, historical and otherwise, of the fishery, they might scout at Moby Dick as a monstrous fable, or still worse and more detestable, a hideous and intolerable allegory.” When you finish Moby-Dick, there is wonder at the book ideally because there is wonder at the whale, a superman of his type, an imposing vision of all whales.

Joel Cuthbertson

Joel Cuthbertson is a writer from Denver. His short stories and essays have appeared in Electric Literature, The New Atlantis, The Millions, and more.