In Praise of CliffsNotes Study Guides in the Age of AI

Joelle Renstrom Reconsiders What Teachers Used to Dismiss as a Shortcut

Here’s something I never expected to say, especially as an educator: I miss CliffsNotes. Those of us who went to school (or parented or taught) between the 1970s and 1990s probably didn’t appreciate how good they were, especially because there wasn’t much to compare them to. CliffsNotes were among the first study guides designed for difficult texts and then later for subjects such as math. Many students embraced the new technology to enable procrastination and lazy homework habits, but also, sometimes, to gain better understanding of readings. Regardless, the guides had a bad rap. That wouldn’t be the case now.

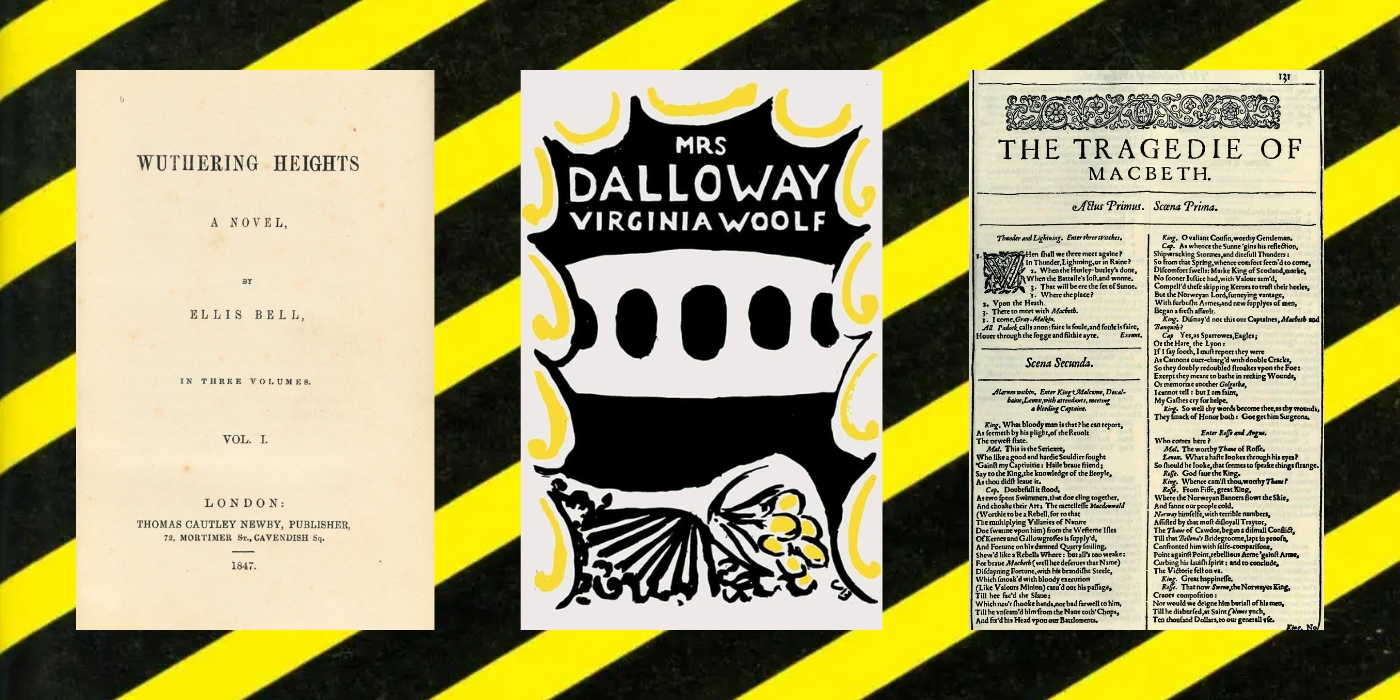

CliffsNotes for students who struggle to get through Bronte, Woolf, or Shakespeare seem laughably analog in the time of ChatGPT, but CliffsNotes offer genuine analysis and even scholarship. The difference between CliffsNotes and today’s computerized counterparts encapsulates the disintegration of knowledge, particularly of reading comprehension.

I hadn’t thought about the yellow and black paperback guides in years until I found some in my parents’ basement. Were they mine or my brother’s? Which one of us struggled with Mrs Dalloway and Wuthering Heights? I was an avid reader and an English major, so one might assume they belonged to my brother, but CliffsNotes were ubiquitous enough that I used them too—not on every assignment, but sometimes. Everyone did. A walk down just about any high school hallway would reveal tell-tale black and yellow edges sticking out of countless Trapper Keepers.

Teachers and parents often (unsuccessfully) banned students from using CliffsNotes. Only slackers used them, they claimed, and if students really wanted to learn something, they’d read the book—they’d do it “right.” The guides were such a cultural phenomenon that they featured on an episode of the Cosby Show when Theo and his friend Cockroach discover “Cleveland Notes” as a workaround to reading Macbeth. Claire Huxtable is furious to learn of her son’s Shakespearean shortcut and the parents force their son to read the full text, which culminates in a successful and iconic “Shakespeare rap.”

Thumbing through a CliffsNotes guide now is something of a revelation. The Wuthering Heights guide offers over 60 pages on Heathcliff and Cathy’s tempestuous relationship, analysis of Brontë’s writing style, biographical inspiration, and discussion questions. The author of this version of the guide, Janet C. James, has a doctorate from the University of York in England and the writing demonstrates it. One sentence about how readers might feel about Bronte’s work contains 79 words and eight commas:

Men and women who, perhaps naturally very calm, and with feelings moderate in degree, and little marked in kind, have been trained from their cradle to observe the utmost evenness of manner and guardedness of language, will hardly know what to make of the rough, strong utterance, the harshly manifested passions, the unbridled aversions and headlong partialities of unlettered moorlands hinds and rugged moorland squires, who have grown up untaught and unchecked, except by mentors as harsh as themselves.

While the effort one expends to digest CliffsNotes is less than the effort of reading an entire text, it’s not nothing. That’s one reason I’d be delighted if my writing students used CliffsNotes instead of ChatGPT or even Wikipedia if they’re tempted to use a summary. The amount of work it takes to use CliffsNotes might even encourage some students to read the text itself. Regardless, the guides require reading comprehension skills and don’t offer random, hallucinated, or uncited thoughts about the text.

CliffsNotes have at least four main advantages over contemporary tools when it comes to literary analysis—advantages I didn’t see or appreciate until ChatGPT stormed onto the scene. The first is that one knows exactly who provided the information. The writer’s name is on the guide and they get credit (and payment). The second is that the information comes from scholars,, not random scraps of common information on the internet. The company says its guides are written by “real teachers and professors,” though it later revealed that grad students often write the material.

As scholars in the field, the expertise of the authors generally precluded the need for fact-checking, so inaccuracies inevitably occurred. Such inaccuracies can be addressed and corrected more easily than ChatGPT’s hallucinations can. CliffsNotes updated their guides in 2000 to address concerns from teachers and to prioritize direct engagement with the text and critical thinking.

The third advantage is that CliffsNotes authors directly cite the text and quote important portions, rather than relying on vague summaries or inaccurate references. Lastly and most crucially, CliffsNotes don’t generate writing that students can pass off as their own. Sure, they can try to plagiarize CliffsNotes, but it’d be easy to identify the vocabulary and style as not theirs.

The guides require reading comprehension skills and don’t offer random, hallucinated, or uncited thoughts about the text.

University students have become savvy at using and obscuring their ChatGPT use. Evidence, including the New York Magazine feature, “Everyone is Cheating Their Way Through College,” confirms many teachers’ fears and experiences. At a recent Boston University panel about AI use, students distinguished between using ChatGPT as a tool and as a crutch. Students know that’s an important distinction and insist they do the former. But when asked about whether ChatGPT’s suggestions apply to other assignments and subjects, students at the panel said no. The predominant lesson isn’t a transferable skill or approach—it’s that ChatGPT can do their work without them having to learn anything. Given the commodification (and rising costs) of education, that perspective is increasingly common.

Students use ChatGPT as a performance enhancing drug, complete with the fear that not using it will place them behind their peers who do. I worry that the conversations I have with students about style, about replacing passive constructions and empty subjects with actual subjects and better verbs, etc—all of them have the unintended effect of driving students toward ChatGPT, not away from it. Given the embrace of ChatGPT by so many copywriters, editors, and publishers, I don’t see that changing any time soon.

CliffsNotes were never a replacement for reading original texts, even if they helped students pass tests and write papers. But now, with the benefit of hindsight, they seem much closer to the real thing and vastly superior to the disembodied, often inaccurate information ChatGPT provides. ChatGPT spits out iterations of iterations and copies of copies until the information doesn’t make sense anymore. Semantic satiation, the repetition of a word over and over until it stops making sense—offers a chilling metaphor and preview of what’s happening not only with language, but with ideas and thinking itself. Misinformation accumulates with each share, retweet, and repost, acquiring additional layers of lies, disinformation, and prejudice. Those inaccuracies then become part of the datasets used to train ChatGPT. On and on we go.

Socrates famously lodged many critiques against writing. He feared that written words, whether intentionally untrue or unintentionally misconstrued, would result in the spread of misinformation, especially among “ignorant audiences.” He predicted that fake news would persuade people, but not even he could predict that machines, rather than humans, would produce the words that facilitate it.

A recent essay about the “synthetic knowledge crisis” sums up the problem facing higher ed: that it’s “no longer a space for the pursuit of truth, but a clearinghouse for well-formed but meaningless arguments – endlessly generated, infinitely circulated, and utterly devoid of the intellectual struggle that once defined what it meant to know.” Considering the number of spam emails I’ve received offering “free ChatGPT for every college student in America,” and considering the fact that schools such as Boston University are developing their own version of ChatGPT, I anticipate this crisis to worsen. Perhaps we have CliffsNotes to thank for the current trajectory of short cuts. Or perhaps we could chart a new course by looking back at what they offered to us—and what they required of us.

Joelle Renstrom

Joelle Renstrom is a science writer who teaches at Boston University and works at Maison Green, a houseplant company.