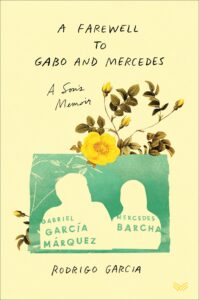

In Memory of My Parents, the Late Gabriel García Márquez and Mercedes Barcha

Rodrigo Garcia Shares Formative Memories of His Mother and Father

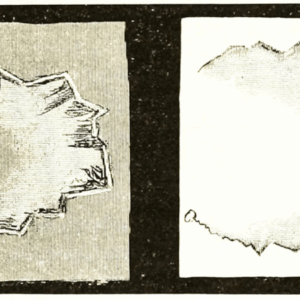

Most of my father’s drafts of work-in-progress were salvaged by my mother behind his back, because he was strictly against showing or preserving unfinished work. Many times during our childhood, my brother and I were summoned to sit on the floor of his study and help him rip up entire previous versions and throw them out—an unhappy image, I am sure, for collectors and students of his process. His papers and his reference library went to the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, and my mom took great pleasure in the opening ceremonies of that collection. Both my brother’s family and mine were there, and she enjoyed and took shelter in the company of her grandchildren.

Two years after my father’s death, we took his ashes to Cartagena. They were placed inside the base of a bust (uncanny in its resemblance to him), in the courtyard of a colonial building, now open to the public. There was an official ceremony, preceded and followed by the obligatory open-house cocktail party at my parents’ house. Like the one around the time of my father’s death, it went on for several days, but since the mood was more jovial, my mother made sure there was live music late into the night. I found the days somewhat emotional and perhaps a little tiring but, curiously, I thought at the time, not too much. It all seemed quite bearable. On my final day there, I stopped early in the morning at the courtyard for one last look at the resting place of the ashes. It was stunning to think they would be there, that he would be there, for a very long time, centuries perhaps, long after everyone now living was gone. The ride to the airport was a sad one, and twenty-four hours after landing in Bogotá I was hospitalized with a bladder infection and a blood clot in my leg. Perhaps the previous days had been more stressful than I thought.

My mother died in August of last year, and I am surprised by how quickly her stature has grown for me. I am unable to walk past a photograph of her without spending a moment looking at it. Her face seems kinder and more beautiful than ever, even in old age. A lifelong sufferer of anxiety (and perhaps unaware of it), she was nevertheless enormously capable of enjoyment.

Her interest (like my father’s) in life itself and in the lives of others was inexhaustible. My feelings about my father, though loving, were complicated by his fame and talent, which made him several people that I’ve had to work to integrate into one, always bouncing back and forth between mixed emotions. There are also complicated feelings regarding the long, painful goodbye that was his loss of memory, and the guilt of finding some satisfaction in feeling temporarily more mentally powerful than him. My feelings toward my mother are now, surprisingly, utterly uncomplicated. This is the kind of statement that makes therapists raise their eyebrows, and yet it’s true. She was afraid of big expressions of emotion, and in our childhood she encouraged us to keep a stiff upper lip. But with time I came to understand that this was a condition that she inherited from her parents, who very likely inherited it themselves. She didn’t even know she was afflicted with it, and whenever I suggested she might benefit from therapy or medication, her reaction was unequivocal: “No. No soy una histérica.” (No. I am not a hysteric.)

Many times during our childhood, my brother and I were summoned to sit on the floor of his study and help him rip up entire previous versions and throw them out—an unhappy image, I am sure, for collectors and students of his process.

I am thankful that I was able to understand this while she was still alive, and to accept it, and so what is left is only affection and an infatuation with the life force that emanated from her. She was frank and secretive, critical and indulgent, brave, but afraid of disorder. She could be prickly and judgmental but also quick to forgive, especially when a person shared their troubles with her. Then she was on their side forever and won over their devotion.

With my brother and me, she was not physical, but profoundly affectionate in her attitude, increasingly so as the years went by. Her complex personality has surely contributed to my lifelong fascination with women, especially multifaceted women, enigmatic women, and what are often referred to, I think unfairly, as difficult women.

I have a renewed admiration for my parents. I admit that this perspective (some would call it revisionism) is not uncommon. Absence makes us grow fonder and more forgiving, and we recognize that our parents were walking on feet of clay like everybody else. In my mother’s case, I am amazed at how, given the period and place she was born into, she grew into the person she became, holding her own or even commanding the world that my father’s success offered them. She was a woman of her time, with no higher education, a mother, a wife and homemaker, but many younger women with big lives and successful careers openly admired and envied her grit, her resilience, and her sense of herself. She was known by her friends as La Gaba, a nickname based on my father’s Gabo and therefore patriarchal, and yet no one who knew her believed she had grown into anything but a great version of herself.

In a restaurant two years before her death, my mom told me that after her, the first born, her mother had two babies who died in infancy. I was surprised that I had never heard this. I asked if she had any recollection of it, and she said yes. She remembered clearly her mother holding a dead baby in her arms. She cradled her left arm, showing me how.

“Why haven’t you told me this before?” I inquired.

My mother was frank and secretive, critical and indulgent, brave, but afraid of disorder.

“Because you never asked,” she replied. Silly me. Sometime later I asked about it again, hungry for more details, but she denied not only having told such a story but also that she had ever seen a deceased baby sibling. I was dumbstruck. This was not senility or dementia. Her memory was always ironclad. I insisted. “No. It never happened,” she said with finality. I let it go that day, but I was resolved to return to that mystery again in the future, in case the wind had changed, but time ran out.

I also spent fifty years of my life not knowing that my father had no vision in the center of his left eye. I found out while accompanying him to the ophthalmologist, and only because the doctor mentioned it after the exam.

I wish I knew how my parents remembered their younger selves, or that I had even an inkling of what they thought of their place in the world, back when their lives were confined by the small towns of their Colombian childhoods. I would give anything to spend an hour with my father when he was a rascal of nine, or with my mother when she was a spirited girl of eleven, both unable to suspect the extraordinary lives that awaited them. And so, in the back of my mind is the preoccupation that perhaps I didn’t know them well enough, and I certainly regret that I didn’t ask them more about the fine print of their lives, their most private thoughts, their greatest hopes and fears. It’s possible that they felt the same about us, for who can fully know their own children. I am eager for my brother’s thoughts on this, since I am sure a home is a very different place for each one of its inhabitants.

A decision regarding the future of the house awaits us. My brother and I are enthusiastic about visiting the house museums of writers and artists of the past, and of other unhappy successful people of that ilk, so we are leaning in that direction. I am a little surprised, nevertheless, by my willingness to open the doors of our own family home to anyone and everyone. Perhaps it’s a desperate stab at defeating the passage of time, or at least at sparing us the heartache of having to empty it and sell it to strangers.

Absence makes us grow fonder and more forgiving, and we recognize that our parents were walking on feet of clay like everybody else.

The death of the second parent is like looking through a telescope one night and no longer finding a planet that has always been there. It has vanished, with its religion, its customs, its own peculiar habits and rituals, big and small. The echo remains. I think of my father every morning when I dry my back with a towel the way he taught me after seeing me struggling with it at the age of six. Much of his advice is always with me. (A favorite: be forgiving of your friends, so that they may be forgiving of you.) I remember my mother each time I walk a guest to the front door when they’re leaving, because not to do so would be inexcusable, and whenever I pour olive oil on anything. And in recent years, the three of us look back at me from my face in the mirror. I’ve also endeavored to guide my life by their seldom spoken but unimpeachable rule: do not be crooked.

Much of our parents’ culture survives in some form in the new planets created by my brother and me with our families. Some of it has merged with what our wives brought, or chose not to bring, from their own tribes. With the years, the splintering will continue, and life will lay upon my parents’ world layers and layers of other lives lived, until the day comes when nobody on this earth holds the memory of their physical presence. I am now almost the age my father was when I asked him what he thought about at night, after turning out the lights. Like him, I am not too worried yet, but I am aware of time. For now, I am still here, thinking of them.

__________________________________

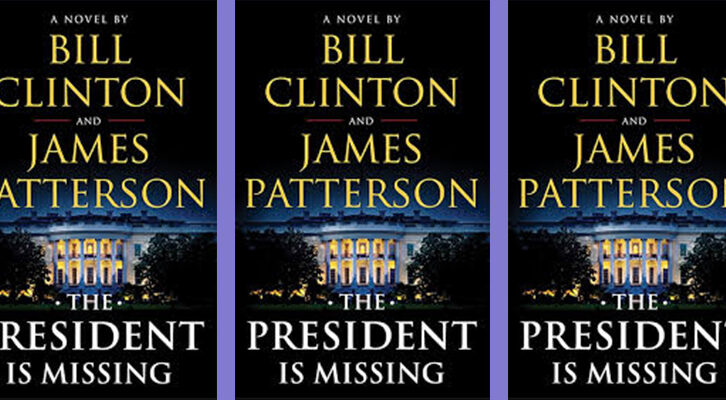

Excerpt adapted from A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes: A Son’s Memoir of Gabriel García Márquez and Mercedes Barcha by Rodrigo Garcia. Published by HarperVia. Copyright © 2021 HarperCollins.

Rodrigo Garcia

Rodrigo Garcia was born in Colombia, grew up in Mexico City, and now lives in Los Angeles with his family. He studied history at Harvard University before becoming a screenwriter and director. His theatrical films include Nine Lives, Albert Nobbs, and Last Days in the Desert, and he has directed episodes of Six Feet Under, The Sopranos, and the pilot of Big Love, for which he received an Emmy nomination. He was a writer, executive producer, and series showrunner for HBO's In Treatment, and directed several of the series' episodes.