In Memoriam: Stanley Plumly

Dan Halpern, Jill Bialosky, and Carl Phillips Remember the Former

Poet Laureate of Maryland

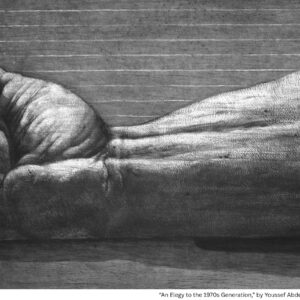

Stanley Plumly, poet and Professor of English at the University of Maryland, died on Thursday, April 11, 2019 of multiple myeloma at the age of 79. He was the author of ten poetry collections, including Old Heart (2007), winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and the Paterson Poetry Prize, and finalist for the National Book Award; and most recently Orphan Hours (2012) and Against Sunset (2017). He also wrote four works of nonfiction, including Elegy Landscapes and The Immortal Evening, winner of the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism.

Jill Bialosky, Carl Phillips, and Daniel Halpern celebrate Plumly’s life and work.

*

A dinner party is the occasion of Stanley Plumly’s The Immortal Evening. Robert Haydon, then England’s well-known history painter, hosted a party in December 28, 1817 to celebrate his progress on his latest painting, “Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem.” Among those he invited were three figures pictured in that painting: John Keats, William Wordsworth and Charles Lamb. While Plumly circles the evening itself, exploring the eminent figures and their work, The Immortal Evening’s central argument concerns immortality. What makes aspects of art immortal? While the three writers achieved immortality, Haydon has been mostly forgotten. This was a central preoccupation of the eminent scholar and poet, Stanely Plumly.

I knew him, first as his student, at Ohio University when I was 19, as a graduate student at the University of Iowa in my twenties, and decades later as his editor at Norton for his last three books of poetry, Old Heart, Orphan Hours, and Against Sunset and his prose trilogy, Posthumous Keats, The Immortal Evening, and most recently Elegy Landscapes.

As a teacher, Stan was unrelenting in his concern for the poem itself and its authenticity. He could not abide work that did not seek to explore human passion, pathos and emotion. In the classroom he was in his element, his diction clear and precise as he dared his students to reach further.

As a poet, he is a master of syntax and formal elegance. His lyric narratives are profound, beautiful and moving; his early work about growing up in working class Ohio with an alcoholic father and bereft mother, a landscape poet, if you will, seeking truth and the sublime in human connection and the natural world.

As a person, he was generous and kind. In his later years, he was in his element, happy in his late marriage, writing at the height of his powers, uninterested in poetry wars or fashion, pursuing the quest for immortality and the sublime in both his prose and poetry. One can see its reach in the final lines of one of his last poems, “At Night,” published in March on the Academy of American Poet’s website.

And so much loneliness, a kind of purity of being

and emptiness, no one you are or could ever be,

my mother like another me in another life, gone

where I will go, night now likely dark enough

I can be alone as I’ve never been alone before.

The Immortality Evening celebrates friendship and art as sustenance and inspiration. It is no surprise that Stan himself loved grand dinners, with friends, immortal evenings now to those who attended. Those who knew Stan, his students and former students, poets, friends, remember his hearty laugh, warmth and kindness, his love of good food and fine wine, and like his beloved Keats, as a poet who saw art as a “friend to man.”

–Jill Bialosky

*

The poems, yes—their elegance of line; their precision of eye; their proof that sturdiness is also grace, or can be. But the generosity and openness of the man are what most stand out for me when I think of Stanley Plumly.

I didn’t expect us to have much in common when I first met him, years ago, at Bread Loaf. Race, queerness, generational difference . . . One of the best lessons I ever learned from him was to check my assumptions. I’ve known few minds as capacious as Stanley’s; fewer, still, for whom friendship came close to sacred. We crossed paths infrequently, yet the resonance of each encounter makes it seem otherwise. “Call me Stan,” he’d say, and I’d promise to remember next time. Memories. “Or if it’s spring they break back and forth / like schools of fish silver at the surface.” It’s spring here, Stan; it’s spring again—wherever you are.

–Carl Phillips

*

Back in the late 80s and early 90s, four male friends had what we then called a Boyz Night. We were Russell Banks, Stanley Plumly, William Matthews and myself. What was discussed at that table remains at that table. We lost Bill in 1997 — and last week, April 11, we lost Stanley. It’s been a bad year for poets and we’re only four months in.

I met Stanley in the early 70s. He was already “an important poet,” having publishing two very well-received collections. I bought his third at Ecco, Out-of-the-Body Travel. He would also become one of the most astute and intuitive critics of contemporary poetry, publishing long, highly anticipated essays on the landscape of American poetry. He was also known as the poet with the best hair. In those days, that was a distinction, of sorts. The rest of our group had no such distinctions, except what we each brought to the table. Stanley wrote some of the most memorable poems of the last forty years, as well as remarkable books on Keats and the artists Turner and Constable.

Our Boyz table contained a shitload of marital history — I think the table average weighed in at 3.5 weddings, although I was only on my first (and last). Stanley was our leader, another distinction, married more than five (?) times. But that was because he was the true romantic among us, a guy who just didn’t believe in dating. And he was as good a friend as he was a poet. But a poet he was to his core, the thing that mattered as much to him as his breathing in, and his breathing out.

–Daniel Halpern

*

Read “Out-of-the-Body Travel,” a poem by Plumly:

1.

And then he would lift this finest

of furniture to his big left shoulder

and tuck it in and draw the bow

so carefully as to make the music

almost visible on the air. And play

and play until a whole roomful of the sad

relatives mourned. They knew this was

drawing of blood, threading and rethreading

the needle. They saw even in my father’s

face how well he understood the pain

he put them to—his raw, red cheek

pressed against the cheek of the wood . . .

2.

And in one stroke he brings the hammer

down, like mercy, so that the young bull’s

legs suddenly fly out from under it . . .

While in the dream he is the good angel

in Chagall, the great ghost of his body

like light over the town. The violin

sustains him. It is pain remembered.

Either way, I know if I wake up cold,

and go out into the clear spring night,

still dark and precise with stars,

I will feel the wind coming down hard

like his hand, in fever, on my forehead.