In Favor of Speed:

Write Fast, Fix Later

Mateo Askaripour Offers a Method of Getting the Work Done

Let’s talk about lobsters. These sea insects, whose etymological history includes once being defined as “spider-like creatures” and “locusts,” weren’t always symbols of luxury, fine dining, and social mobility. In fact, as early as the 1600s, lobsters were in such abundance that they were considered food only fit for servants, prisoners, and other untouchables. One essayist, John J. Rowan, captured this sentiment in 1876 when he wrote, “Lobster shells about a house are looked upon as signs of poverty and degradation.”

However, as railways began to spread across America, train owners discovered that people in other parts of the country—especially inlanders—didn’t know what lobster was, or about its unsavory reputation, so they claimed it was exotic and started to sell it in their dining cars. Passengers would return home and request the delicious crustacean they ate on the train, making it more popular.

And to further increase the lobster’s allure, chefs figured out that torturing the creature by preparing it live, instead of cooking it after it was dead, made it that more appetizing. By the 1950s, the lobster had risen far from its bottom-dwelling days of the social food chain and become a favorite for the rich, beautiful, and well-cultured. Even Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Foster Wallace penned an entire essay dedicated to the creature, in which he wrote, “Lobster is posh, a delicacy, only a step or two down from caviar.”

This shift in the public perception of lobster can be attributed to many factors—supply and demand, advertising, and endorsements from influential individuals—but what it boils down to is perceived value, which is a person’s assessment of the value of a product or service, based on a handful of criteria, in comparison to its peers. And like everything from lobster to Beanie Babies, perceived value has an immense impact on how we value art, as well as artists’ ability to finish the projects they begin—which can be dangerous.

Imagine walking into an art gallery—perhaps something you’ve done before. The scattered and colorful brushstrokes of a painting on the wall catches your eye. As you take it in, trying to understand the “essence” of it, the curator stands beside you and whispers, “Breaktaking, isn’t it? It took her a decade to complete.”

This shift in the public perception of lobster can be attributed to many factors—supply and demand, advertising, and endorsements from influential individuals—but what it boils down to is perceived value.

BOOM! Whether you actually like the piece or not, you’re not as likely to flinch when you hear that its asking price is $500,000, because this artist spent ten years of her life creating this painting that you’re not sure you understand. On the flipside, if you were told that it took the artist, despite having honed her craft for two decades, ten minutes to create this same piece, which is being sold for $500,000, you’d likely shake your head and walk away. This assumption of quality based on the amount of time it takes to create a work—whether it’s a painting, book, film, play, or even a meal—presents a serious flaw in how we value art both financially and socially.

When I was starting out, in 2016, I was working at a tech startup and still very much entrenched in that world, a world where one of the most common sayings is “fail fast;” something I believed and agreed with then as much as I do now. With this “fail fast” mentality, paired with no formal writing training to speak of, I began to write, and I wrote fast.

My first manuscript took four and a half months to complete, a total of 97,998 words. It wasn’t a particularly good piece of work, nor did it earn me what I was seeking—an agent and a book deal—but I used it as a way of learning how to write, and, more importantly, I finished it. This rhythm—finishing as quickly as possible while not judging myself too much during the process—is what I’ve found to have helped me progress in my literary career the most.

From that first manuscript, I wrote another, this time after having read a craft book and receiving some feedback from agents on my first work. After about a month of outlining, I wrote that one in two weeks. It was 53,743 words and far more organized and focused. Yet again, I ended up nowhere. But at least I got to nowhere fast.

After doing some soul searching, deciding not to give up, and re-dedicating myself to the task before me—completing a book that felt true to me and those I wanted to serve with it, in the exact way I wanted to—I began my third manuscript in January 2018. It took me about five months to complete the first draft, which came out to 160,708 words, eight months to work on a handful of other drafts before getting an agent, and roughly six months after that to get a book deal and some Hollywood movement. Praise be to the literary gods, it will be published in January 2021. If I had hemmed and hawed, worrying myself over every little detail and listening to the prevailing advice that one needs to take time, years even, to produce a work of quality, I would have become stuck and likely have never published a book, or even completed my initial draft.

This assumption of quality based on the amount of time it takes to create a work—whether it’s a painting, book, film, play, or even a meal—presents a serious flaw in how we value art both financially and socially.

The idea that you need to spend years on papercuts and perspiration just to get a draft down—not a final version—is as ridiculous as all of the other expected behaviors for artists. We see it in movies and on TV all the time: to be a writer, you must write in coffee shops, agonize over every single sentence, struggle financially yet still live in an unrealistically large New York City apartment, be misunderstood, have the ability to walk into a face-to-face meeting with your editor and/or agent and beg and plead for an extension until some lightning bolt of genius strikes you at 3 a.m. and you complete a classic overnight, be white and attractive. I eloquently sum up my feelings about all of those privileged and classist stereotypes and expectations in two words: fuck that.

At one point during my journey, in 2018, I ran into a writer, in a Manhattan bookstore-cum-coffee shop, who has won many awards, is commercially successful, and is an overall great person—I’m now fortunate enough to call them a friend. But back then, in that coffee shop, they didn’t know me from Adam. Seeing them, I said, “Yo! I just saw you at an event last night. Can I buy you a cup of coffee?” They said yes, and we had a brief conversation about writing. During it, they asked, “How old are you?” “Twenty-six,” I replied. They nodded and said, “Word, write your book as fast as you can. Don’t listen to all that other bullshit. You’re young, and are changing faster than ever, so you need to get your vision out and completed before how your change ruins it.” This was the advice I wanted to hear.

But not everyone does. And you’re more likely to find people who scoff at anyone who attempts to write a book, of any kind, quickly. Many folks speak with awe of others who have taken five years to write a book; their audience, editor, or agent show equal admiration when they repeat these words. And that’s fine, but, shit, Anthony Burgess supposedly wrote A Clockwork Orange in three weeks, so don’t give me that mess.

There are, however, many successful writers who don’t try to bang out a book in a few months, and prefer to take it nice and easy. One of these people is Colson Whitehead, two-time Pulitzer winner, National Book Award winner, MacArthur Genius, Carnegie Medals for Excellence in Fiction winner, and more, but who’s counting? Whitehead, in more than one interview, has said that he only writes “One or two pages a day. . .That’s eight pages a week. Eight pages a week over a year, that’s a book.” It’s hard to argue with someone of Whitehead’s eminence, and because he’s a writer I revere, so I won’t. A year, from the perspective of some, is fast for a first draft. What I’m advocating for, above all, is sitting your ass down, especially if you’ve never finished a book before, and doing it even quicker, if you can.

The difficulty, though, which the lobster faced in its early days, is in public perception. Because even if you do create something truly original, or, as people in creative industries love to say, “fresh”—like lobster straight out of the waters of Maine—you may run the risk of having your work devalued, specifically financially, if the gatekeepers that be find out that it didn’t take you years of toiling away in the dim glow of a candle to complete it. This could mean the difference between a five- and six-figure advance.

This rhythm—finishing as quickly as possible while not judging myself too much during the process—is what I’ve found to have helped me progress in my literary career the most.

So what do we do, lie? No, I wouldn’t say that. I would propose that you proudly stick by your guns, tell whoever is asking however long it took you to complete your work, and keep it moving. If they value it less, push back, and if they still don’t give you what you believe you deserve, either settle for less until you’re in a position not to, or don’t and see what other options exist. If one of the cockroaches of the sea can go from being despised to costing $8 a pound, so can you. That analogy may not work, but you get the point. Or the claw? Okay, I’m done.

__________________________________

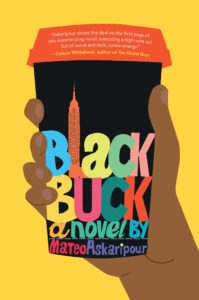

Black Buck by Mateo Askaripour is available now via Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Mateo Askaripour

New York Times bestselling author Mateo Askaripour wants people to feel seen. His first novel, Black Buck, takes on racism in corporate America with humor and wit. Askaripour was chosen as one of Entertainment Weekly’s “10 rising stars to make waves,” and Black Buck was a Read with Jenna Today show book club pick. Most recently, he was named as a recipient of the National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35” prize. This Great Hemisphere is his second novel. He lives in Brooklyn. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter at @AskMateo.