In Defense of My Family Business: The Soap Opera Storyteller

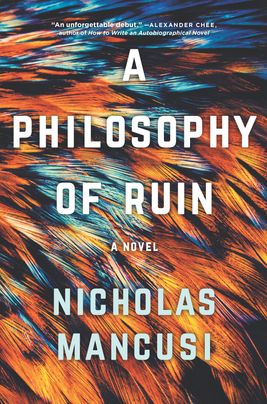

Nicholas Mancusi on the Importance of Plot and Inventiveness

We all know what a cultural critic means when they say that something is like a soap opera: they mean that it relies too heavily on plot for its impact, that it’s all twist and no substance, or that the limits of credulity are stretched to breaking in the service of a cliffhanger. Lazy plotting is bad, surely, but lazy criticism is bad, too, and I’ve always thought it was boring to use an entire art form as a pejorative.

I’ll admit that my defense of the form is not only aesthetic, but personal. My grandmother, Claire Labine, was a screenwriter who, after writing scripts for Captain Kangaroo and a few other daytime dramas, co-created a soap opera called Ryan’s Hope, which ran for 13 years. Later, my mother and uncle joined the family business, and, for a time during the years of my childhood most redolent of childhood (roughly ages 5 to 8, old enough to form memories but tweendom nowhere in sight), they were a co-headwriting team on General Hospital, a seminal soap which began its run in 1963 and is still on the air today (some 14,000 episodes and counting).

During these years, my mother worked largely from a small office in our first home on suburban Long Island, and scripts and outlines would pile up around the house, drafts on yellow printer paper, finals on white. My younger brother and I would use the blank paper on the reverse side as our drawing pads, staying up late in our bunk beds to draw robots and dinosaurs and B-17s on the back of Luke and Laura’s dialogue.

I would sometimes eavesdrop on her conference calls and overhear heated debates about the proper arc for a character or the resolution of a plotline. When we stayed home sick from school, we could watch GH with Mom on the tiny TV in the kitchen while she made us soup, and the fun thing was to watch the credits for her name.

So when I hear the term “soap opera,” the first thing that comes to mind isn’t evil twins or sudden amnesia but rather the effort that it takes to create four new narratives each week, something like 260 hours of television a year, and to do it a way that keeps an audience invested for decades, for an actual lifetime. This is not something that can be done with narrative trickery. Story is needed. And for story you need plot.

When I hear the term “soap opera,” the first thing that comes to mind isn’t evil twins or sudden amnesia, but the effort it takes to create four new narratives each week.

I had to learn this lesson for myself when writing my first novel, A Philosophy of Ruin. I had a character that I was interested in: a young professor of philosophy who reflected a shade that my life might have taken but did not. And I had created a world for him on campus and given him a set of fears and preoccupations that mirrored my own. And I had put him in a tough set of circumstances to see how he’d react: his mother’s sudden death, his father in debt to the quasi-philosophical conman who brought her under his sway in her last days, and his career in jeopardy due to an accidental affair with a student.

And yet, somewhere around what felt like it must have been the halfway point of the story, I was totally becalmed under what non-writers often call writer’s block. I made no significant progress for at least a year, tinkering with what I had already written while I awaited inspiration on how to move forward.

Looking back now, I see that I needed that time to gather the courage to introduce higher-voltage plot elements—seduction, blackmail, a backpack full of cocaine, car chases, gun fights—in order to make sense of my story. I had wanted desperately to write a novel that would be called smart, and we all know, as the voice of the lazy, boring critic whispered in my ear, that plot is not smart. Plot is an indulgence. Plot is mere fun. Plot is wasted words that could otherwise be dedicated to the real work of literature. Plot is soap opera.

Well, stuff that. When I allowed myself to introduce these plot elements, I was able to draw out the themes I had established to their logical conclusion, to play them out in the big beats of a plot rather than merely in the characters’ interiors. And I saw that it was only plot that could throw the characters against one another with enough force to create the sparks that would keep the reader interested.

After I decided to cross into that territory, the story finally began to make sense to me. After another year’s work or so, I looked up and realized I written something that people would call a thriller, instead of the “campus novel” that I had begun. Are there hundreds of good books, books that I love, that consist mostly of characters not doing much other than wandering around, quietly mistreating one another, and being sad? Of course. But it turns out that that’s not the kind of book I can write.

If a plot is functioning correctly, it’s because of the way that it interacts with the other elements of the story, rather than distracting from them. If you’ve gotten your readers to invest in your characters, plot is how that investment is paid off.

If a plot is functioning correctly, it’s because of the way that it interacts with the other elements of the story, rather than distracting from them. If you’ve gotten your readers to invest in your characters, plot is how that investment is paid off. A car chase is not compelling because it’s cool how fast the cars are going. It’s compelling (if it’s working right) because you care about the fate of the person behind the wheel.

The General Hospital plot that my grandmother was most proud of involved a plot point, that, granted, might strain credulity, but illustrates the narrative impact that can only come from placing your characters under as much duress as you can fathom. One father, after his young daughter was rendered brain-dead in a tragic car accident, makes the decision to take her off life support so that her heart could transplanted into the body of her ailing cousin, saving the second life.

Some clips from this plotline are up on Youtube. It’s devastating stuff, even if you haven’t been following the characters for years. But what my grandmother was most proud of was that after the story aired, there was an appreciable increase nation-wide in organ donation sign-ups.

Years ago, during the time when I had that first half of a novel in need of a plot, I gave the work in progress to my grandmother to read. She was encouraging, but she never got to see the second half. (She died, in a certain kind of mercy, on the evening of the 2016 election.) In hindsight, I’m sure she was able to able to see what I couldn’t: that the pieces were on the board but the real work not yet begun. I regret that she isn’t alive to hold the final book in her hand, but I’m glad that I was finally able to employ the lesson of her body of work: that it’s plot that pumps the lifeblood through a story’s heart.

__________________________________

Nicholas Mancusi’s A Philosophy of Ruin is out now from Hanover Square Press.

Nicholas Mancusi

Nicholas Mancusi has written about books and culture for the New York Times Book Review, Washington Post, Daily Beast, Miami Herald, Boston Globe, Minneapolis Star Tribune, Newsday, Newsweek, NPR Books, American Arts Quarterly, BOMB magazine, and other publications. He lives in Brooklyn.