The reopening of the bookstores is a cause for celebration. When I was a child, in Communist Prague there were long queues of readers in front of the bookshops. There wasn’t as much light entertainment on offer as there was in democratic countries, and people spent a lot of time reading. When I walked from home to school in the morning, I often saw queues forming before the bookshops had even opened. Editions of authors like Proust and Joyce had print runs of tens of thousands in a country which had only ten million Czech speakers. And when a new book by Bohumil Hrabal came out—an author who was banned by the censor for many years—avid readers would spend the night on the pavement in sleeping bags, in queues that went right round the block. They did so in the hope of buying a copy, because in those days books weren’t reprinted once they were sold out but when the central planning authorities decided, regardless of reader demand, so that if you didn’t get a first edition copy, you didn’t know when you might have another chance. This is what I remember most from my childhood: the queues to get anything at all—bread, fruit, meat—but the longest ones were those in front of the bookshops.

Many years later, I traveled to Moscow to interview some of the last few women survivors of the forced labor camps, the so-called Gulag. I also found that for them, who had personally lived through the horror of those camps, books were a much-prized commodity. One of these women, Gayra Vesiolaya, showed me some little hand-made books of poetry, written in the Gulag. “As books were forbidden, at night we recited these poems, written by some of us, from memory; we preferred to sleep less and humanize ourselves, dignify our lives, with poetry,” she told me. Then I remembered my recent meeting with Irina Emelyanova, the daughter of Olga Ivinskaya, who was Boris Pasternak’s last great love, and on whom the author based the immortal Lara, the main character of Doctor Zhivago. Irina told me that after Pasternak’s death, she and her mother were sent to the Gulag. There, Irina fell in love with a male inmate, a translator of poetry. The two lovers communicated with each other by hiding poems in the bricks of the wall which separated the women’s camp from that of the men. He would leave her French poems, and she would leave him poems by Pasternak, written on tiny pieces of paper.

Galina Safonova was born in a Siberian gulag in the 1940s. Given that the barracks in which she lived with her mother and other women prisoners, was the only thing she knew, she lived there as if it were perfectly natural. And even today she has kept the books which the women prisoners made for her. She picked one up at random: Little Red Riding Hood: the paper was sewn by hand; on each page, drawings had been done with colored crayons and the text of the story had been handwritten with a pen. “How happy each of these books made me!” Galina exclaimed, “It was with them that I learnt to read, they were my only cultural points of reference. I’ve kept them all my life, they’re my treasure!”

Books have been a symbol of resistance on many occasions when there has been an abuse of power.

The Western world must also think of books as a treasure, because it celebrated the reopening of the Italian bookshops, the first ones to do so after the lockdown. Days later, the queues in front of German bookshops reminded me of those in the Prague of my childhood. In Spain, the bookshops were closed for two months and during that time many of us missed them just as much or more than we did keeping fit or having a drink with friends. During the lockdown, when we were confined to our homes, with the police checking we didn’t venture out, many of us found consolation in reading. We listened to live-streamed music and lectures, we enjoyed our favorite films and visited online museums; but we couldn’t do without books for one single day.

Books have been a symbol of resistance on many occasions when there has been an abuse of power. With a book in your hands, even solitude becomes a free and open space. But today as well, in our democratic societies, books and bookstores are points of resistance against those who would turn us into uncritical consumers, citizens spellbound by fleeting idols, governed not by the people we vote for but by the interests of corporations who wish us to be complacent in out lot. To read is to question the apparently obvious, to question what is established, and to enter a bookstore is to let ourselves be surrounded by those who have so many things to tell us so that we may retain our human dignity. These reopenings offer us a great deal to celebrate at last.

__________________________________

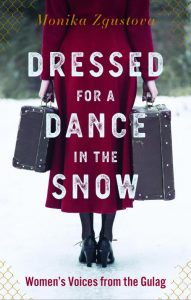

Dressed for a Dance in the Snow by Monika Zgustova is available via Other Press.

Monika Zgustova

Monika Zgustova is an award-winning author whose works have been published in more than ten languages. She was born in Prague and studied comparative literature in the United States (University of Illinois and University of Chicago). She then moved to Barcelona, where she writes for El País, The Nation, and CounterPunch, among others. As a translator of Czech and Russian literature into Spanish and Catalan—including the writing of Havel, Kundera, Hrabal, Hašek, Dostoyevsky, Akhmatova, Tsvetaeva, and Babel—Zgustova is credited with bringing major twentieth-century writers to Spain. Her book Dressed for a Dance in the Snow: Women’s Voices from the Gulag (Other Press, 2020) was a World Literature Today Notable Translation of the Year.