In a Family of Readers, Packing Up My Late Father's Library Was Hardest of All

Seth Greenland on Remembering, Retaining, and Failing to

Exorcise Sentiment

I hold my father’s copy of Mein Kampf in my hand and wonder if it should be saved, donated, or burned in the backyard. Will the day arrive when I attempt to hack my way through Hitler’s turgid opus? Or do I want to observe the look on the face of the clerk at the local donation center when she sees that noxious title? And what was Leo Greenland, husband, father, grandfather, successful advertising executive and generous supporter of multiple charities—some of them Jewish—doing with a paperback edition of Mein Kampf anyway? Bequeath, retain or incinerate: Our choices.

We are breaking down Dad’s library. His heart gave out six months earlier at 91, and my wife Susan and I have flown east to meet my brother Drew and close down the house. My mother died 20 years earlier and with the eternal absence of both parents the scrim that separates me from death has vanished. Dad was born in the Bronx and my mother in Brooklyn. They ascended high above their social origins and with a well-developed sense of herring-flecked drollery would occasionally refer to themselves as Bix and Brooke.

The bedrooms were easy to pack up; the living room and the den done on autopilot. It would have been easy enough to turn the kitchen into an emotional minefield. There are the beautifully painted dishes my mother shipped from Spain, the ones on which she prepared her signature dish of scallops with feta cheese and tomatoes. The carving knife Dad had wielded so many Thanksgivings or the stained wood tray I had made in elementary school might easily have sent me tumbling down a Proustian rabbit hole, unable to emerge for hours. These objects resonate, but their emotional power pales compared to that exerted by the books.

In a house of readers, what more than books allows access to the inner lives of its occupants? When a person you love has recently died, there is often an urge to keep them close in some tangible way. With dusty fingers we work our way through libraries of the dead and read their lives, written in volumes about other subjects.

Born to uneducated immigrant parents, Dad was an autodidact (a word he never would have used) whose lifelong search for knowledge and meaning led him on a journey that began with books about marketing and took him from there to the Greek philosophers, particularly Aristotle and Plato. In between, he accumulated a veritable Waldorf salad of titles. There were over a thousand. You can’t keep them all.

Bequeath, retain or incinerate. We vow to exorcise sentiment, sort rigorously, keep it moving.

The library is on the second floor of the house, overlooking a frozen lake. No other houses are visible, only ice and bare trees against white sky. When packing our dead father’s books on a silent January day, gray winter light flooding in, thoughts of eternity wrestle with the anodyne task at hand. An old bestseller easily drops into the donation pile, but then I am brought up short by a high school yearbook from 1938 and open it to the picture of Dad as an 18-year old, his entire life about to unfold, nothing more than a glint in his brown eyes. He looks like my brother—not my brother Drew but a brother of mine in some other dimension, one where we are the same age as our parents and our grandparents and our children and the normal distinctions no longer abide. He is me and I am him. The idea of people you love living on within you no longer seems like such thin gruel.

I decide to keep a leather-bound edition of Treasure Island, a book I haven’t read since the fourth grade, perhaps because I might read it again, but if I’m being honest, more because it helps me remember that I was once a child and lived with parents who gave me books like that and The Catcher in the Rye and Huckleberry Finn and to whom I owe gratitude that deepens like the notes of a descending scale on a double bass.

Bequeath, retain or incinerate. We vow to exorcise sentiment, sort rigorously, keep it moving.

There are histories and biographies, art books, novels, books about golf, classics from antiquity, the entire oeuvre of Ogden Nash, leather-bound volumes both antiquarian and recent, all of them revelatory in one way or another. There are books that my brother and I had given as gifts and we open them to read the inscriptions: “I know if a book has the word ‘Jews’ or ‘Israel’ in the title, you will like it. I hope I’m right this time. Love, Seth.” In the Alec Guinness memoir A Blessing In Disguise, I had written “To Mom, A blessing undisguised.” And, of course, I had to stop and stare out the window while I collected myself and thought about all the childhood hours my mother read to me, a book open on her lap as I lay in bed listening.

Turning back to the shelves I pick up a volume of Remembrance of Things Past—the Proustian rabbit hole itself!—inscribed in 1938 by my now 90-year-old Aunt Claire to my paternal grandfather, a four-times married, pathological narcissist from Poland who cut a swathe through the ladies of the Bronx. It is difficult to imagine him having had time for Proust, but it makes me think of my aunt at 16, poignantly hoping that her perpetual disappointment of a mostly-absent father might somehow be interested in this book.

And then there is this depth charge: an edition of Now We Are Six by A.A. Milne, copyright 1927, and inscribed as follows: “To my belove [sic] son Leo. Father.” When my grandfather abandoned his family in 1928, leaving my grandmother to face the Depression alone with three children, it left my father with an unseen scar. If Dad could be said to have had a primal wound, this was it. To touch the book, a frayed, orange hardback with faded gold lettering, is to hear once again the painful stories he told me about his father, the serial remarriages, the emotional abuse, the years-long estrangement.

Although my parents were not bibliophiles in the traditional sense, every house they occupied had a floor to ceiling wall of books. The first time I ever saw a swastika it glowered at me from Dad’s copy of William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, shelved near his edition of Mein Kampf, cheek-by-jowl with Deborah Lipstadt’s The War on the Jews. When interested in a subject, he examined it from all angles. I had helped myself to the Shirer years earlier. As for the worthy Lipstadt, it lands in the donation pile.

There is a collection of classics that includes Lucretius, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. I have no idea if he read these particular editions, but their contents were manifest in his behavior. He was both an Epicurean and a man who tried to see with the unsurpassed clarity of the Stoics. The art books are a testament to his uxorious nature. My mother was the art lover and they were purchased for her: eclectic volumes of Wyeth, Grandma Moses, El Greco, Monet, Miro, Picasso, Van Gogh, Hopper, Christo, Magritte, Matisse, Garry Winogrand, and Irving Penn. As we sort, all the museum visits come flooding back, my mother’s endless quest to make us interested in things besides baseball cards or digging holes in the backyard. Several volumes go into the box I will ship to California.

Three of my Sunday school textbooks have been saved, books I had not laid eyes on in over 40 years. One of them contains the following self-penned inscription: “In case of fire, burn this first.” I can’t imagine either of my parents ever saw it. Their silence in such an event would have been unimaginable. The strange feeling of wanting to excoriate the wisenheimer who scrawled such offensive words overcame me, to remind the little shit of the book burnings that lit Germany in the 1930s, and then, in the kind of psychological jiujitsu that arrives with age, the dissonance of having come to embody the parental position is duly noted. Would I have freaked out if I had discovered my son had done the same?

One of my 40-year-old Sunday school textbooks contains the following self-penned inscription: “In case of fire, burn this first.”

It is difficult to fathom why there are several multivolume collections of humor among Dad’s books. My father embodied many qualities when I was young. He was loving, forthright, strong, decisive, and occasionally loud. He was not a teller of jokes. Perhaps the humor anthologies—the S.J. Perelman, the works of Catskills comedian Sam Levenson—were, like Aristotle and Plato, aspirational. His adult life as a propulsive businessman didn’t leave much time for hilarity, and I don’t recall him laughing that much when I was a child. But judging from his library, it appears as if he wanted to. The Perelman volumes go into the California box.

Books on marketing proliferate, many from the mid-century era, his apotheosis. And next to them a worn paperback of Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals, so recently a cudgel with which Republicans were trying to thump President Obama. The business books are all placed in the donation pile, the Alinsky set aside. A first edition of an obscure Graham Greene novel, A Burnt-Out Case, is a major find, but even though Dad aspired to write fiction when he served in the Army during World War II (we encountered several early efforts as we sorted through his papers), there are not a lot of old novels.

There are, however, a great many newer editions of old ones that he had purchased via mail order through something called the Franklin Library. With their gold-lettered leather bindings they have the look of set dressing one would see on a Broadway stage in a production of The Winslow Boy. In his Bronx childhood, our essentially fatherless father had somehow learned to ride a horse with an English saddle. Like Gatsby, he had sprung from his platonic conception of himself, and that image required shelves lined with leather volumes. As Drew slips a leather-bound edition of The Sun Also Rises into his stack, he remarks that it was as if Dad was filling in an area he had missed when he was trying to get somewhere.

A wonderful oddity is Zero Mostel Reads A Book. My parents venerated Zero Mostel, owned several of his signed lithographs, and spoke reverently of having seen him in the American premiere of the Ionesco play Rhinoceros in the late fifties. This particular work is nothing more than a rice-paper-wrapped collection of photographs of, yes, Zero Mostel reading a book. I can tell you: Zero Mostel has an awfully expressive face. This made me wonder how many libraries contain copies of both Zero Mostel Reads A Book and Mein Kampf.

There are books that whisper—from a great distance, their voices barely audible—the quintessence of gone pop culture eras. Passages by Gail Sheehy and Running by Jim Fixx. A beat-up copy of All the President’s Men. Titles that were on everyone’s lips, books that held the light long enough, and died off early enough, to call forth an entire epoch when their jackets are glimpsed. Torch Song Trilogy by Harvey Fierstein, anyone? A one-way ticket to Donationville.

And speaking of plays—my parents were great theatergoers, and although published plays are not represented heavily in the library, the few that are there unleash a cascade of memories: my mother insisting I ask John Gielgud for an autograph (in 1968 when I had no idea who he was), or spending an entire day watching the Royal Shakespeare Company’s epic staging of Nicholas Nickleby or attending the premiere of Angels in America with both of my parents healthy and brimming with life. We donate an omnibus of modern classics, even No Exit by Sartre. I hesitate when I sight, eerily, Da by the Irish playwright Hugh Leonard, a play about a man haunted by the demanding, irascible, loving ghost of his father. I saw the Broadway production starring Barnard Hughes with my parents in 1976. Dad’s copy is with me now.

Some of what was donated: all of the business books and anything having to do with golf. Good as Gold by Joseph Heller did not make the cut and neither did Heller’s Guillain-Barré memoir that I had mistakenly given Dad as a gift. It was the only time he was incredulous at something I had purchased for him. He didn’t do disease. A man of action, he was uninterested in an author’s sickbed ruminations. Born on March 4th, his motto—“March forth.”

A very short list of what I kept: art books, the Collected Works of Ogden Nash, a Bellow novel, Inside the Third Reich by Albert Speer (unlike Hitler’s opus, my brother assured me, Speer is generally considered to have turned out a first-rate book). And my Sunday school texts. At exorcising sentiment, it turns out, I am a failure.

It takes us two days to finish going through the library. Perhaps it could have been done at a brisker pace, but that would not have allowed unhurried time with our mother and father. We load two cars with the donations and head for a public library in a quiet Connecticut town near where my brother lives. There we fill two bins, each the size of a couple of bathtubs, with our cargo of paper and ink and memory. A woman wanders over to see what we are giving away. The inert pile of books is like an open coffin.

As we drive off I wonder about mein kampf. Not the book—that was in the garbage, garlanded with coffee grounds and orange peels—but the struggle, my own struggle, with my father’s legacy, with what to keep and what to let go. We are like our parents in ways we cannot imagine, some beguiling and others less so. But we also, even as adults, sometimes consciously embody their qualities. As parents recede in death and memory becomes porous, certain particulars will linger: a favorite melody, the jaunty tilt of a hat, a library. In those details elements of our own identity can be found.

__________________________________

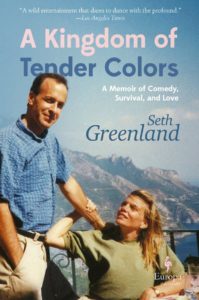

Excerpted from A Kingdom of Tender Colors: A Memoir of Comedy, Survival, and Love by Seth Greenland. Copyright © 2020 by Seth Greenland. Reprinted with permission of the author and publisher, Europa Editions.

Seth Greenland

Seth Greenland is an award-winning playwright, screenwriter, and author of five novels, including Shining City (a Washington Post Best Book of the Year) and The Hazards of Good Fortune (nominated for the 2019 Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger). Born in New York City, Greenland lives in Los Angeles with his wife.