In a Backyard in Texas, Considering the Universe

in an Oak Tree

Jung Young Moon on the Small Mythologies of Place

It’s winter now, and I’m in texas, and I’m writing this, a story about Texas, but at the same time, a story that deviates from being a story about Texas, a story that does, indeed, go back to being a story about Texas, something that I’m writing in the name of a novel but something that is perhaps unnamable.

As is the case with any place in the world, to someone who hasn’t been to that certain place, hearing the name of that place may or may not bring something to mind. Before coming to Texas, I’d never talked to anyone about Texas, and so I didn’t know what came to people’s minds when you said Texas; but what came to my mind when you said Texas was a notorious Texas, perhaps because of murders that took place there, such as the John F. Kennedy assassination, and perhaps because of movies based on the murders—Bonnie and Clyde, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and No Country for Old Men—some of which actually had taken place while others were only partially true, while yet others were completely fictional, and perhaps the murders that served as a direct motif for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre were not the ones that took place in Texas, but in Wisconsin.

I’ve been dividing my time between the Dallas home of D, a novelist, and N, an artist, an American couple who are friends of mine, and a house in C, a small town near Dallas. The house is a 150-year-old Victorian mansion, the kind of house that’s common to the American South, and it’s designated a cultural heritage site of C although there’s nothing special about it, and it has a long L-shaped terrace which is nice to just sit and pass the time on.

Having arrived in mid-November, I sat on the terrace, and when the wind blew I watched acorns fall like hail from the enormous oak trees in the yard, and at night I watched stars through a telescope at the little old observatory in the backyard, and the stars couldn’t be easily observed because of the leaves of the oak trees, but I still saw, through the gaps between the leaves, our fragmented galaxy, as well as parts of other galaxies which, too, had nothing special about them.

There were so many acorns on the oak trees that, if I stood waiting with patience under a tree, I could get smacked on the head by at least one falling acorn, and, if I was lucky, I could get smacked by two in a row, and, if the wind blew just in time, I could get beaten by many at once, and, after getting smacked on the head by acorns, I could think, It’s quite pleasant to get smacked on the head, on purpose and for no reason, by acorns of all things, and so, when I felt down at night, or when I was having trouble falling asleep and, instead, was feeling a sense of solidarity with insomniacs around the world, but was also thinking there was nothing we could do together, or when I didn’t know what I should do, or when I wanted to be punished severely even though I hadn’t done anything wrong, or when I just wanted to get beaten and come to my senses, I would go and stand under an oak tree.

D was working on his second book on Texas, and N, who painted and did art installations, was making a life-sized bronze canine statue that would be placed on a street at the center of C, and which had been commissioned by the town. The statue was to be a re-creation of the logo of Company W—a brand of chili con carne, a spicy stew with meat—as a life-sized bronze statue.

I pictured the members of the (International) Chili Appreciation Society gathering periodically and talking while eating chili about their life with chili.

The brand has now been acquired by a large company, and the taste of the chili has changed too, but some private donors wanted to install a statue in C, where the brand had its beginning, in honor of the brand. N made me do a part of one of the ears of the clay canine she was sculpting, as well as part of the tail, and I contributed part of a fox ear and part of a raccoon tail, both foxes and raccoons being members of the canine family, after which she added clay to the ear and the tail, obliterating the shape I’d created, but, perhaps when the bronze canine statue was finished and placed on a street at the center of C, I could look at it while thinking that inside the statue were parts of the fox ear and the raccoon tail I’d created: parts not existing while existing, or existing while not existing.

We talked about the many statues in small American towns that had been erected in honor of people from those areas, figures holding a baseball bat or glove or a basketball, or a gun or a fishing rod, or a book or an instrument or an invention, or a local product or sowing seeds, or reaping the harvest—all statues that would’ve been better to do without—and N said that the canine statue could turn out to be something that, too, was better to do without, and that it could be the most attention-drawing eyesore, and that it could perhaps draw more attention because it was an eyesore; and then we tried to think of things that could be nice to have, but would be better to do without, but we couldn’t come up with anything besides the aforementioned statues, and so we said that the canine statue could be one of those things.

Later, when we were at a Texas-style restaurant eating a dish with chili in it, N said that the founder of Company W had gotten the name from Kaiser Bill, his pet wild canine, and that he used to go around town with the caged animal in the back of the company truck. She also said that soldiers who were sent to battlefields in Europe during the Second World War ate W’s products from their helmets, and that chili was the official food of Texas, and that the headquarters of the (International) Chili Appreciation Society— established to raise the quality of chili in restaurants and circulate Texas-style chili recipes—was located in Dallas.

I pictured the members of the (International) Chili Appreciation Society gathering periodically and talking while eating chili about their life with chili, about a life in which it was difficult to imagine a life without chili, and just in that moment when I was eating chili, I didn’t feel that I was with the members of the (International) Chili Appreciation Society but was chewing the beans in the chili nevertheless, and I hoped that the controversy over whether or not to acknowledge chili with beans as chili—about which no conclusion has yet been made, it seems, even by the (International) Chili Appreciation Society—would go on being the greatest controversy surrounding chili.

Perhaps at the core of the controversy was the fact, overlooked by many people, that beans were something that didn’t easily entice people to eat them because they weren’t particularly tasty, even though they were good for your health, and also because they put you in a depressed state if you ate too many of them at once, or too often.

Personally, I didn’t have a particular stance on the matter, but I hoped that among the members of the (International) Chili Appreciation Society, the controversy over whether or not to acknowledge chili with beans in it as chili—the essence of the controversy—would become confused or marred; that a conclusion may not be reached easily; and that the controversy would continue in difficulty.

__________________________________

From Seven Samurai Swept Away in the River. Used with permission of the publisher, Deep Vellum. Copyright © by Jung Young Moon. Translation copyright © by Yewon Jung.

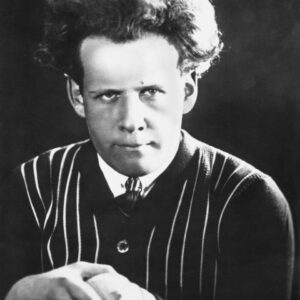

Jung Young Moon

Jung Young Moon, born in 1965, is an award-winning Korean writer and translator. A graduate of Seoul National University with a degree in psychology, Jung is also an alum of the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program. In 2012, he won the Han Moo-suk Literary Award, the Dong-in Literary Award, and the Daesan Literary Award for his novel A Contrived World. He has been a resident at the University of California at Berkeley’s Center for Korean Study and the 100 West Corsicana Artists’ & Writers’ Residency in Texas, the latter of which inspired his novel Seven Samurai Swept Away in a River. Deep Vellum published his novel Vaseline Buddha in 2016, and will publish his linked novella trilogy Arriving in a Thick Fog in 2020.