Imani Perry on Writing the Story of the American South

The Author of South to America Discusses the Space Between Public and Personal Narratives

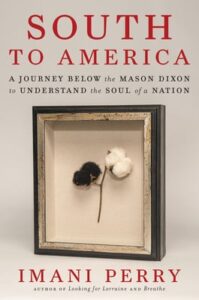

Imani Perry’s South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation comes out this week from Ecco Press. Perry answered questions about writing about the intersection of personal and national history, the cultural ideas associated with the American South, and gaining a reader’s trust.

*

You note in the book that, “We teachers, historians, patriots all have inherited a British inclination to tell history in a linear forward sequence. But that just won’t work for the story of the South. Or the nation.” With that in mind, where and how did you begin the project of writing this book?

Technically, it began with an essay I wrote for Harper’s in 2016, “As The South Goes, So Goes the Nation” which was a kismet-like event. I happened to speak at an event honoring Albert Murray’s legacy at Lincoln Center and met James Marcus there who was then the editor of Harper’s and we began a correspondence that led to that piece. But once I got to the book itself, I guess that started with soul searching. I thought about my identity as a Southerner and particular an Alabaman and asked myself the question of why it is such a strong part of who I take myself to be given that I’ve lived out of the South for most of my life. A large part of the answer is that’s where my family is and always has been.

Growing up I lived a sort of elliptical life of physical departure and return, even though to paraphrase the painter Romare Bearden, I never left the South except physically. To this day, my late grandmother’s voice is in my head with every decision I make, every endeavor I take up. I also had an axe to grind. So much of my early impulse was to correct the record, a kind of defensive posture vis-à-vis my home which I took to be constantly mischaracterized when I traveled to any other region. I wanted people to understand, the South is not some backwards strange other place, but in fact from the beginning been the vanguard of this country, often in terrible ways but also in some extremely beautiful ways. I mean, the moral imagination that came from the spiritual expansiveness and courage of enslaved people is one of the greatest legacies of this country.

There’s this essential tension there, a push pull, between freedom and cruelty, between expression and repression, between exultation and degradation, that is always at work. Knowing that, seeing it from near and far, I knew that telling this story wasn’t going to be a tidy forward march. There’s no a then b then c, sort of movement through the region. If you talk about it that way, you miss its essence. You also can very easily misunderstand why we, as a country, have been fighting the same battles since the colonial period.

South to America weaves together many different threads: it is a history of the American South, an examination of the relationship the country has to the region, and the story of your own experiences there. Can you speak to the importance of invoking your own narrative in this project, and how did you decide to do so?

I’m an academic by trade and training. And standard academic writing takes the position of the dispassionate imperial (and imperious) scholar who makes an argument backed up by evidence, and is dedicated to showing they are “right.” But in truth, writers of all sorts write from a place of passion, curiosity, and commitment. I have decided to be transparent about that. This book came from my heart. So I had to be in it for it to be a true story, in the sense of honesty.

“Inside the house, afraid and contemplative, I rehearsed my own story.”

Also, for me writing is an invitation for others to enter into a room I’ve created: objects, images, sound, tase, scent, vision. And there’s something extremely vulnerable about that. A guest might not like my tablecloth or they might notice a stain on my carpet. That makes me nervous of course, but that’s the only way for intimacy to exist with the reader, especially in nonfiction. And I want that intimacy, and to establish trust from there. A reader’s trust is, I think, a writer’s greatest possible achievement.

You write that, “collectively the country has leeched off the racialized exploitation of the South while also denying it.” How does scholarship and historical writing play a role in breaking through this denial?

There’s really outstanding historical work that supports my claim. I couldn’t have written this book without having spent decades reading serious works of American history. But so much of that academic work is left out of the public consensus narrative if that makes sense. It really is scholars who have established the nation’s economic dependence on the South from the colonial period forward, and specifically the way the racial order undermined the labor movement and possibilities for working class people across the lines of race to push against experiencing exploitation.

But the public narrative generally casts Black history as a story solely about a regional civil rights movement, and a march towards rights-based inclusion. That’s all important of course, but when you lose the context of how national wealth was created, who did what work how and when, how Wall Street and Capitol Hill came to be, and also when there’s not much attention to the history of work period, you lose any deep and coherent understanding of where Black people and working class people fit in American history, and how this country came to be the most globally powerful and culturally influential nation in the world.

Your travels took you across the South, including to West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky, Alabama, and Washington, D.C. (which, as you pointed out, has a unique connection to the concept of southern-ness). How did you map out this project as you were planning it, and did the scope of it change over time?

So, I bought a bunch of physical atlases, the kind we used to have in the car before the internet. And I just spent weeks looking at them, tracing routes with my fingertips, noticing land formations and waterways, and thinking about the histories of the various locales in relation to each other with the land in mind. I also had a series of drives planned, but halfway through the pandemic changed everything. I couldn’t return to a bunch of places I had intended to return to.

“Once I got to a kernel of truth about the South and where it fits in our national story, I became somewhat less jealous of which parts of the country ‘count’ as the South.”

But a strange and beautiful part of my pandemic experience is that my memory became incredibly sharp. All of these stories from the past came flooding back to me. I think that probably happened for many people. And so, inside the house, afraid and contemplative, I rehearsed my own story. And that became part of how the book was composed. I went back, in personal history, and also physically to many places I had been, even while in the house. So the composition of the book is that it is made of multiple layers of past and present.

How did your own relationship to the South change (or not) in the course of working on this book?

The greatest change is that I began with a very rigid idea of what “The South” was and is, which was evidence of my own deep South bias and experience. But over the course of travels and research and memory, I began to see that there is a “south” in a general sense and also “souths” plural. Something shared across various parts of the South, and in distinct ways, is that this incredibly abundant gorgeous land was met with innovation and imagination, but also with incredible greed and a willingness on the part of elites to grind people’s lives down into nearly nothing in the service of their desires.

And then in each part you have the folk, regular people, who used their imaginations as well, to create, to experiment, to make space for themselves. So once I got to a kernel of truth about the South and where it fits in our national story, I became somewhat less jealous of which parts of the country “count” as the South.

How would you advise writers who are interested in exploring political and cultural histories through the lens of their personal story or their family’s story? Where would you suggest they begin, and is there any advice you would offer in regards to conducting research?

So I knew this wonderful woman, Francis Pierce, who was a friend of my godmother’s when I was growing up and she used to say, “Bloom where you are planted.” And it sort of is an analogy to the Elements of Style guidance “write from a suitable design.” Both of those ideas are important for this kind of endeavor. It’s like standing where you are planted, at first, and digging deep from there: How did this house get to be here? How did my people get to this house? Who lives here with me? Are the plants out in the back native to this place? Are they weeds or food? Where could we walk from here? When people ran from here, why did they go? Why do I love or hate this street? How did this place make me who I am today? Those kinds of questions can be pursued emotionally, but they can also be pursued through historical methods. Curiosity is the lifeblood of the whole thing, and love of course. That’s indispensable.

__________________________________

South to America by Imani Perry is available via Ecco Press.