Imagining a Liberated Future for Palestine

Ilan Pappé Explores Political Futures in Palestine and Israel

A proper imagining of liberation cannot rest content with describing the end game: the day of liberation itself and the hard work the day after. This is only the starting point. No less important is the effort to imagine the main stations on the journey to liberation—the things we can do, the responsibilities of others, what happens outside of our control, and how we might nonetheless prepare for unpredictable eventualities.

I’ve decided to outline a path imagining the mini-revolutions I’ve discussed in this book in the form of a fictional diary, from 2027 to 2048. This isn’t a diary of an individual life but a window into a sweeping political transformation, through the eyes of one person. The entries are all written on May 15 (the day the British Mandate ended in Palestine) to demonstrate that a better future will also change history, in how we remember and commemorate it.

*

POST-ISRAEL PALESTINE, MAY 2048

May 15, 2048: 5 Edward Said Street / The corner of 101 Nuh Ibrahim Avenue, Mount Carmel, Haifa

I woke up, happy to be alive still at the age of ninety-four. Every new day is a blessing, and even if I am not particularly religious, I utter first in Hebrew, “Hashevah Lael,” then in Arabic, “Alhamdulillah,” and then in English, “Thank God.”

The pills and the doctors kept me alive all these years, and I think I am still mentally sound although, of course, physically somewhat disabled. But am I? The occasional doubtful glances my two sisters cast at me make me think that maybe out of kindness they treat me as if I still have all my faculties.

Mixed marriages at that time were by no means easy, and we faced judgment from both communities, but in 2048, there is more acceptance; at least, I hope.

The rest of the family’s attitude is no better. My two daughters and my grandchildren have long left the country and resettled all over the place, but they come regularly to visit. As the time passes between them seeing me, their countenances are even more concerned. Sometimes I catch them looking at me with pity but also with compassion. Again, we must all thank God in our three languages.

After my second wife passed away, one of my daughters, Nadia, named after my late first wife, began talking about coming back with her children, Nidal and Abir, to Haifa. You might wonder why my children have Arabic names, although I am Jewish. Both my wives were Palestinian. My second wife was the daughter of a Palestinian father and Jewish mother. Mixed marriages at that time were by no means easy, and we faced judgment from both communities, but in 2048, there is more acceptance; at least, I hope.

Physical fragility has made me more aware of the ground than I ever was previously. I can tell you what is under my feet like a hound, whether it’s a cigarette butt, a piece of paper, other litter. Every now and then I find a qirsh (the old agora was replaced by qirsh and the Israel shekel by the new Palestine lira, also known as a pound) or sometimes even something more valuable. I do make an effort to be taller and erect, especially when I reach the panorama spot where I can see how the city’s skyline has changed over the last decades.

I was invited to be part of the committee in 2042 that discussed how to bring back the beauty of the city destroyed by the Israeli government’s obsession with de-Arabizing Haifa, before the Wathba, the revolution of 2040 that turned Israel into the new Palestine without repeating its mistakes. There are still debates going on about the name for the new state, with a lot of support for the name Isratin, regardless of its associations with the Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi, who initially proposed it in his 2000 book.

Before the Wathba, the skyline of Haifa was dominated by the ugliest tower of them all: the Ministry of Interior building, constructed in the 1970s on the ruins of the old city, which included a famous covered market. It, too, faced destruction alongside all the historic buildings and architectural marvels. This cultural heritage had been deemed by Israel to be too Arabic, while the state wanted Haifa to be visually and architecturally European.

The new streets’ names not only reflected the joy of liberation but also celebrated living in dignity, equality, and without fear—names invoking hope, humanity, and freedom.

In fact, for the sake of building the Sail Tower, to honor the assassinated prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, at the turn of the twenty-first century, the municipality destroyed the old and beautiful Ottoman Saraya. As a young scholar at the time, I protested with others before the demolition took place, but we were told that this was an inevitable phase in the development of the city. Well, we had the power to turn post-modernity into early modernity, at least in one building.

I was part of the planning committee and voted with others in favor of demolishing the horrible tower of the Ministry of Interior. It was a joyful day of destruction—no people inside, of course; all precautions were taken. I kept the clip from al-Karmil al-Jadid reporting the event.

From our Haifa correspondent, Wasfi Khroub:

The rocket-shaped building—the municipality hoped it resembled a ship—of the Ministry of Interior today was demolished in a clinical operation. We had to stand far way, although with the cutting-edge technology it was possible to bring it down without causing collateral damage to the nearby old buildings that were shielded in due course. This was genius! I must admit, I hated this building, where I had to plea for an ID or a passport in which it stated that I am an Arab by nationality and a Muslim by religion. I hope we will have new IDs, or even better, no IDs at all.

But we were not only busy demolishing. We were also restoring pre-1948 street names and left intact the less offensive Hebrew street names. I was on the naming committee for a while and cheekily proposed the name of the street I lived in: Edward Said Street, next to Nuh Ibrahim Avenue, intersecting with Leila Khaled Square.

We also did it so that returning refugees would feel more welcome, after keeping these street names themselves for decades in the refugee camps. The new streets’ names not only reflected the joy of liberation but also celebrated living in dignity, equality, and without fear—names invoking hope, humanity, and freedom.

The exit to the street used to have stairs, but my son-in-law, Yaqub, had them removed, and now I can easily stroll into the street. In fact, he is the only one who happens to be in Haifa right now, and yesterday we decided to meet in my favorite coffeehouse, al-Awda (The Return), run by Rami Safadi.

Rami, the coffeehouse owner, is a grandson of a refugee from Haifa, whose original house is long gone. Refugees such as Rami wanted to live as nearby as possible to their original family homes. In Rami’s case, the special agency created by the government, under the name of the “Restorative Justice Committee,” helped Rami to find a place to open as a business not far from his family’s original 1948 home.

I say “we”; I hope this is not too presumptuous, but I really feel part of the “we” in the new Palestine that has emerged in the last years of my life.

He is quite a character, in his forties, a handsome man with a warm smile that conceals the tough life he passed in a refugee camp in Lebanon. Rami returned to Haifa, under the Abu Sitta repatriation program adopted by the new national assembly in the summer of 2041. I attended the meeting from the gallery of the guests in the refurbished building of what used to be the Knesset, the old Israeli parliament, renamed the National Assembly.

If we were iconoclastic when it came to ugly high-rises in the midst of old towns, we were quite restorative in the way we treated functional buildings such as the Knesset. I say “we”; I hope this is not too presumptuous, but I really feel part of the “we” in the new Palestine that has emerged in the last years of my life.

The coffeehouse boasts a fine balcony, overlooking the bay, much less polluted than it was thirty years ago when the industrial complex of refineries and biochemical plants caused many in the vicinity to die from cancer and left others seriously ill. Now, every day, you can see the view all the way to Ras al-Naqura and the upper Galilee, and on a particularly nice day you see the white top of Jabal al-Sheikh, Mount Hermon, the only mountain Palestine possesses.

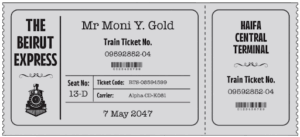

Another new addition to the view is the coastal railway line built during the Mandatory period now reopened from Haifa to Beirut in which a bullet train can be seen speeding along the coastline. Just recently a new line from Beirut to Türkiye (by now I hope people have adjusted to the new name of the country, introduced in 2022) was added (it gives me great joy whenever there is an alternative to flying!). I wish I were forty again and could embark frequently on these trips, as I have always dreamed of doing. I added a ticket here as this is both a diary and a scrapbook.

Courtesy of Hayley Warnham for One World Publications

Courtesy of Hayley Warnham for One World Publications

Unexpectedly the door was shut. It was usually wide open. I did not give it too much thought and pushed it open. I was greeted by a hip-hop version of “Happy Birthday” in its Arabic version, “Sana Helwa Ya Mony, Sane Helwa Ya Mony.” Old friends, students, and colleagues, not in large numbers but an impressive quorum, were there congratulating me for the day…I had to make the usual joke that this is one effective way of killing me, but probably also the most pleasant one!

My son-in-law opened with praises; I will not repeat them but will not deny I enjoyed them. He then handed me a present: a bound folder with the notes I gave him a while ago for my memoirs. He had turned them into this elegant folder of papers. The cover page showed a very flattering old photo of myself, from years gone, and it read in Arabic “Yawmiyat Moni” (Moni’s Diary).

I have to admit I reorganized and edited the entries a bit as yearly reports, otherwise my notes would have cost the world an entire forest. Yes, even in the 2020s, I wrote in a notebook. Can you believe that? I might have been the sole upholder of good handwriting in that decade.

Walking back from Rami’s coffeehouse, I passed by houses where in former times Jewish friends of mine lived. Some of the houses, into which refugees entered in my hometown, had been vacated by frightened Jewish citizens with foreign passports who could not envisage living in a non-apartheid country. I knew some of them very well—after all, I spent most of my long life in Haifa. My grandchildren asked me, “Why didn’t you try to dissuade them?” I answered that if this was their decision, it meant that their racism had so deeply distorted their personalities that neither the Palestinian refugees nor I could do much about it. We should all, I said to them, pay more attention to, and care about, the more conscientious Jews who understand that a just society benefits them as much as it benefits the Palestinians.

Our new reality remains precarious, but so far it survives.

Those who remained and were originally liberal or left Zionists as events unfolded on the ground leaned more and more toward a non-Zionist ideological position. This was a painful process for them because most of the leftists in Israel left the country in the wake of these events. The Mizrahi Jews, the Arab Jews, were deeply divided. Some rejoiced in actually living once more in a state that was more Arab than European, but some left, especially the Moroccan Jews, who were welcomed by their original country of origin, and others left for France. I still hope that these are temporary departures and that time will prove to them that this is also their homeland.

By now, in 2048, after almost ten years of negotiations, we have a stable government and a normal parliament. The new PLO is still the largest party, and the prime ministers, first Asif al-Safari, who retired according to the new constitution after five years, and now Nasser al-Fahmawi, made it very clear that they see all the Jews as equal citizens.

There is also the Hebrew National Party in the parliament advocating for more cultural autonomy for Hebrew institutions, and we still have a strong left party and political Islamist parties. Coalitions are formed and dissolved regularly, not always in a very amiable way, but nothing so far has undermined our new reality of equal coexistence. Some of the Jews are still serving in senior positions of the professional army that replaced the Israel Defense Forces and in the police force and as a very small number in the intelligence service. Our new reality remains precarious, but so far it survives.

But you can read about all these major developments in the history books. I fought all my life for this new reality to unfold and was fortunate to see it with my own eyes. I did not leave the country, nor was I fearful of the future. I was never an onlooker—I always tried to be a participant rather than an observer. I was lucky. I was born in Haifa and I will die in Haifa.

Currently I live not far from where I was born. But I grew up in an exclusively Jewish neighborhood. For years now, many Palestinians have changed the shape and character of this neighborhood, including some of the more affluent members of the refugee community who reclaimed old houses or lived near them after the Israeli Law of Return was abolished in 2040 and the initial free flow of Palestinian returnees was made possible. Many were still out there in exile waiting for their moment of return.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Israel on the Brink: And the Eight Revolutions that Could Lead to Decolonization and Coexistence by Ilan Pappé. Copyright 2025. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.

Ilan Pappé

Ilan Pappé is a professor of history at the College of Social Sciences and International Studies at the University of Exeter in the UK and the director of the university’s European Centre for Palestine Studies. His widely lauded books include The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Ten Myths About Israel, and A History of Modern Palestine. He writes for the Guardian, the London Review of Books, and elsewhere.