Illustrating the Visual Illusions of Walter Benjamin's Mind

On Wandering Through—and Recreating—a Writer's Marginalia

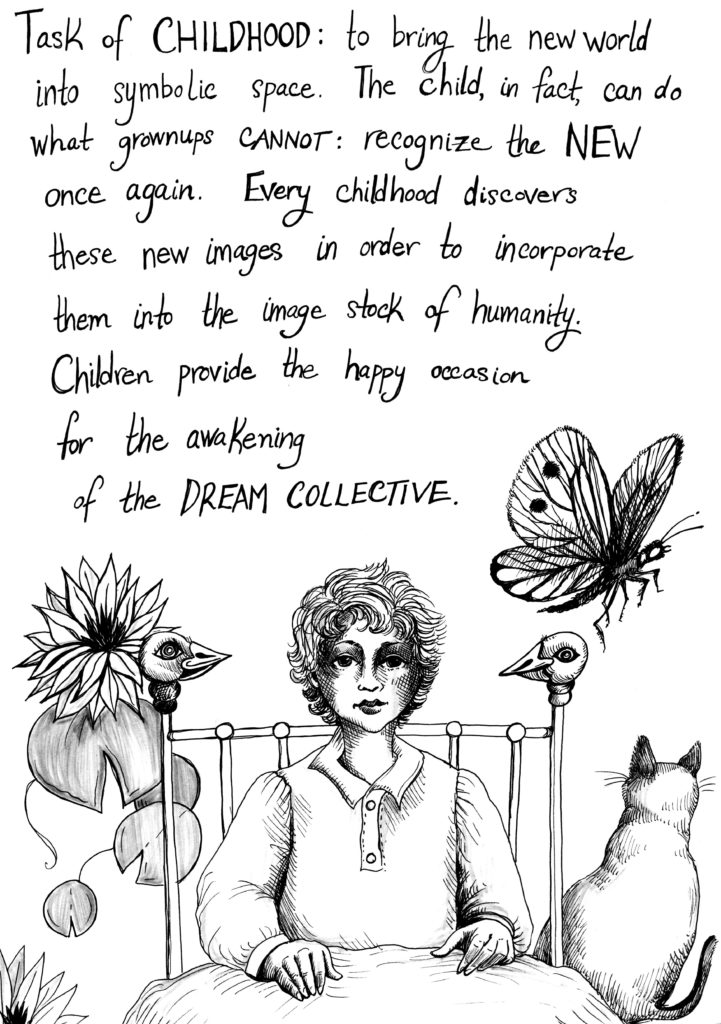

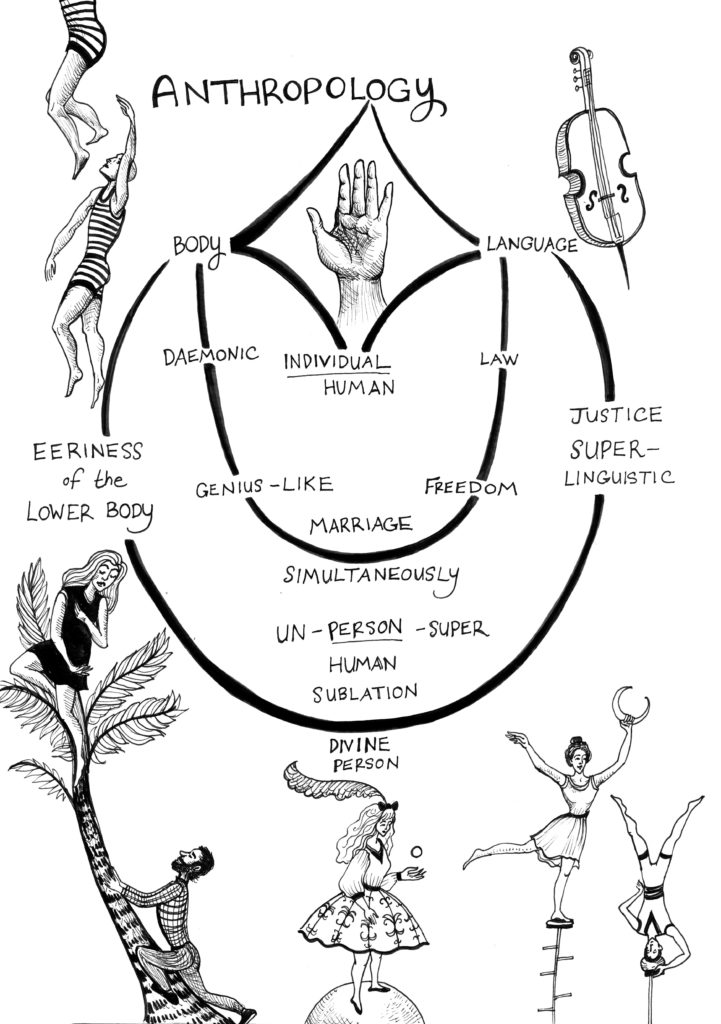

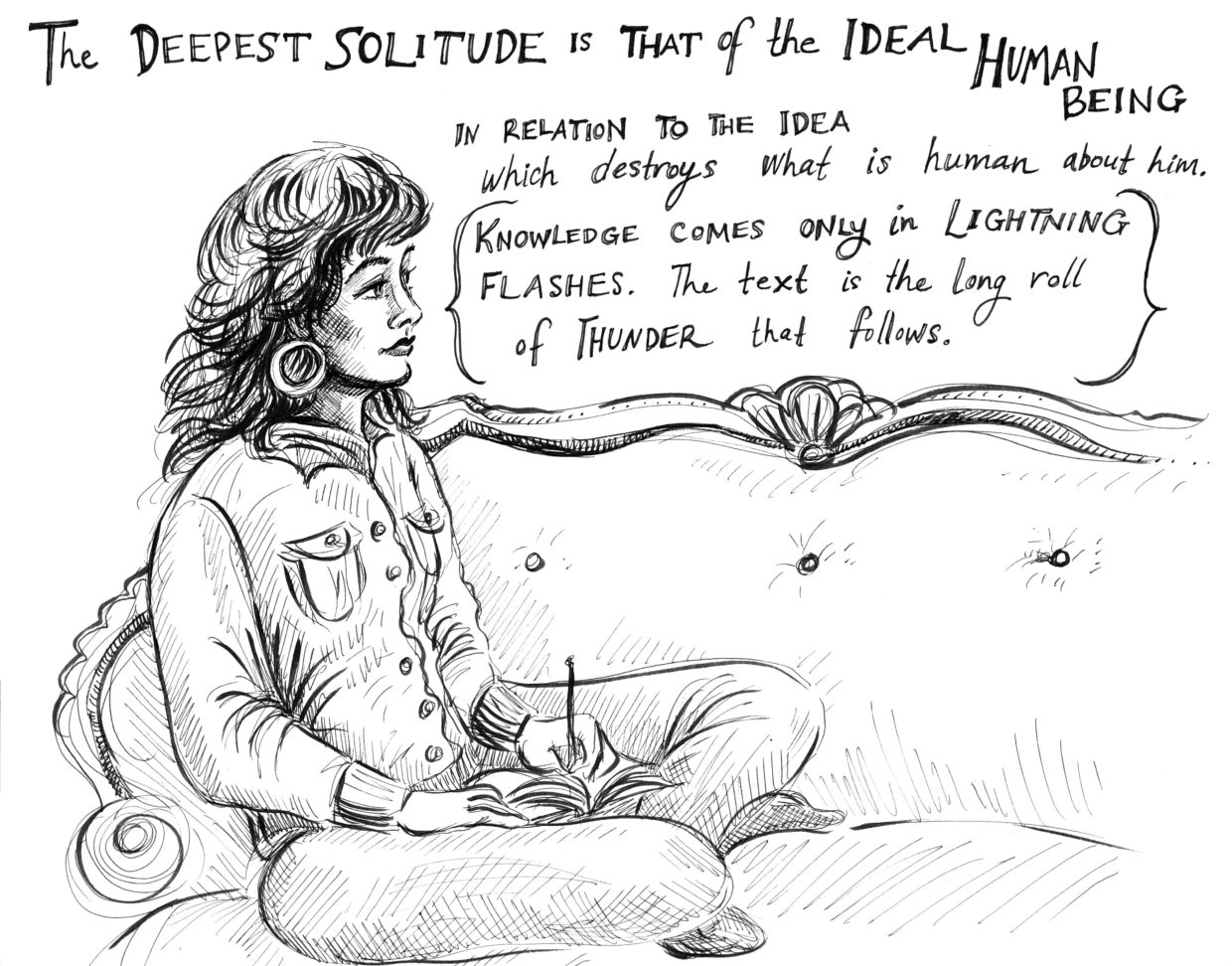

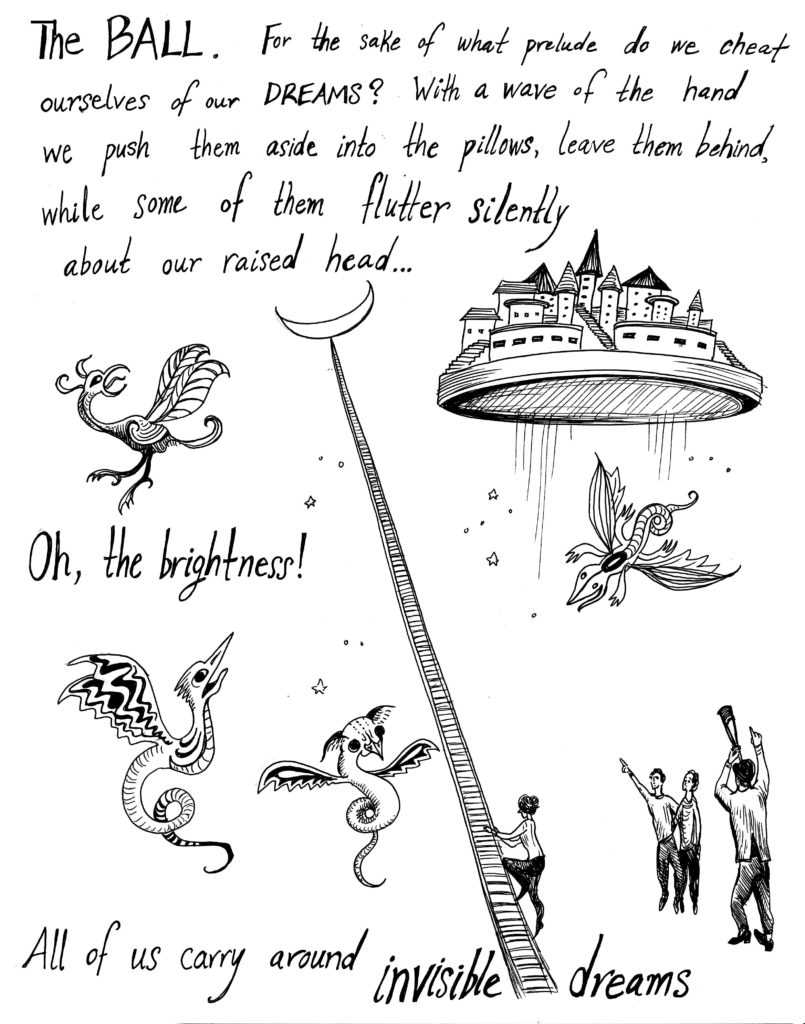

Walter Benjamin took a unique approach to all of his literary and critical writing, one of constant flux in form and content, one of experimentation and fragmentation. His work rests just outside the margins of the 20th-century European literary canon, and Benjamin the scholar stands apart from his contemporaries in the Frankfurt school of philosophers. Perhaps he belongs instead at the table of literary brooders—both authors and their characters: Hamlet, Baudelaire, Duras, Plath, Bernhard, and Sebald—all of whom establish themselves as outsiders, set apart from “normal” behavior and creativity. These melancholics isolate themselves from society to wallow in solitude and ennui. Victor Frankenstein, for example, holes himself away in a windowless attic for a year to research and then constructs a creature out of cadavers. Benjamin, alone in his mind palace, drove himself nearly to madness with his philosophical investigations of the dark arts of capitalism, the phantasmagorias of underground Parisian commerce, and the mechanization of art in the age of technology.

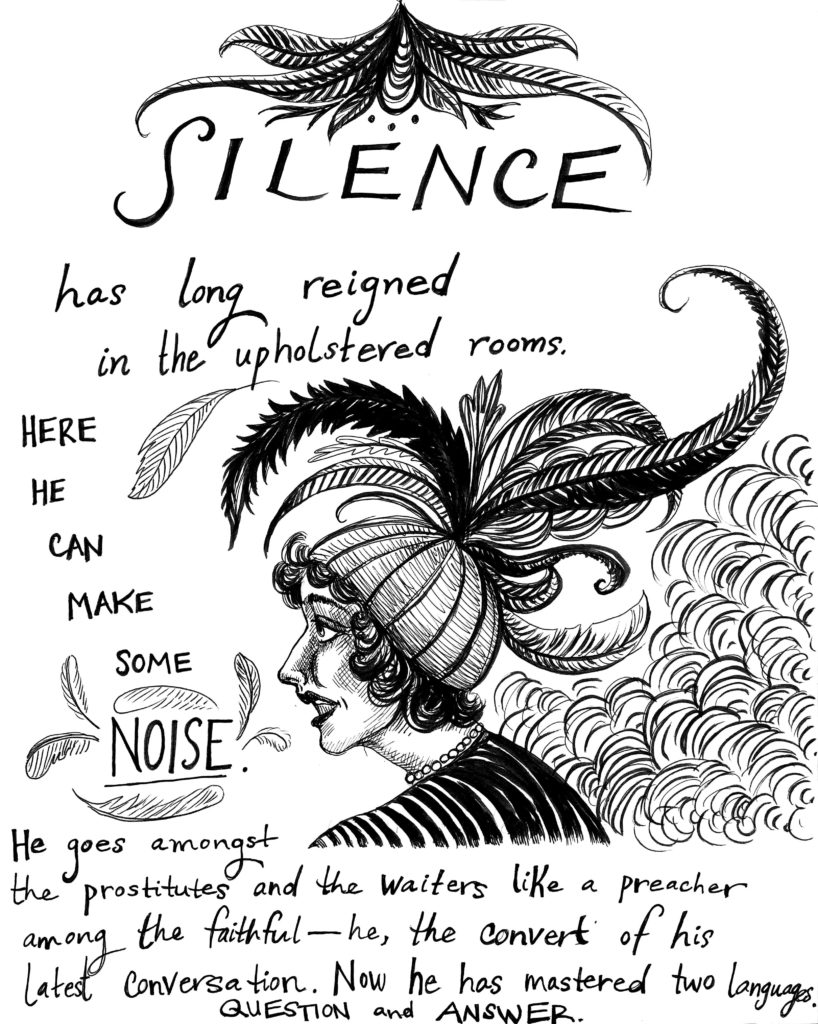

Many of these melancholics—both the artists and their creations—wander aimlessly, either in pursuit of, or to escape from, their own dark states of mind. Both Walter Benjamin and Baudelaire wrote about the flâneur who saunters through the streets of Paris, usually at night, observing prostitutes, performance artists, and other spectacles of the human condition. These cultural observers appear to be exploring the streets of their own minds, more than the cities which they trace with their slow steps. W. G. Sebald’s narrator in Rings of Saturn drifts slowly, alone, down the dreary coast of Suffolk in search of—what, a landscape haunted by death? During a conversation with Joseph Cuomo, Sebald spoke about the asystematic approach that he took to his research and writing process: “If you look at a dog following the advice of his nose, he traverses a patch of land in a completely unplottable manner. And he invariably finds what he is looking for.”

© Frances Cannon

© Frances Cannon

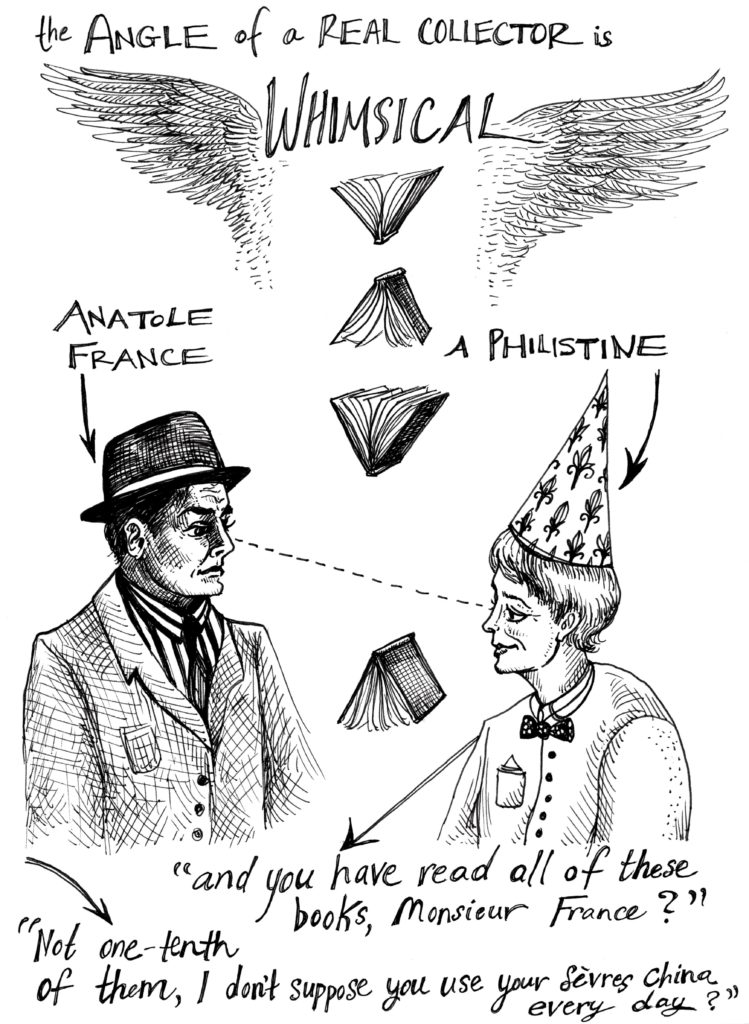

This wandering, then, is nonlinear, not goal-oriented. Walter Benjamin wrote about the collector as an archetype, a generalized character who is to be both admired and pitied for his efforts of curating objects and books—one who revels in the non-goal-oriented process of accumulation more than in the objects themselves. It is the chase, the search, the quest, the walk itself that defines the work. The narrator in Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse admits that “it is love the subject loves, not the object . . . it is my desire I desire, and the loved being is no more than its tool.” The love object dissolves in the process of loving; the mourned object dissolves in the process of mourning. The writing process is just as important as the result.

Among this chorus of melancholic characters and writers, Walter Benjamin’s work appeals to me for its form—in his prose, he drifts between rigorous essaying and whimsical lyricism. I am also drawn to Benjamin’s diverse, interdisciplinary interests. He was a man of letters, a respected art critic and essayist, a translator, an obscure philosopher of the early 20th century, a journalist of the dirty underbelly of urban centers, and above all else, a collector, fulfilling his own favorite literary archetype. He collected cities, jobs, books, snow globes, postcards, paper ephemera, vintage objects, modern objects, treasure, and junk. Benjamin’s obsessive collections are beautiful in their chaos. His most celebrated archive of intellectual scraps is the Arcades project. In this unfinished magnum opus, he endeavored to catalogue his observations of the Parisian underground market—the labyrinthian arcades, which housed, above all, outdated objects representing the remnants of a lost era. These alleyways of glass and steel hosted prostitutes, black-market merchants, and an enchanted fairyland of “rolls of licorice . . . stamps, letterboxes, naked puppet bodies with bald heads . . . combs swim[ming] about frog-green . . . umbrella handles . . . bird seed . . . sets of teeth in gold and wax . . ..”

© Frances Cannon

© Frances Cannon

The arcades appealed to Benjamin as a demimonde, containing just as much darkness as magic. Benjamin had not yet reached the age of 50 before his work on the Arcades project was arrested: while in exile in Catalonia in 1940, he overdosed on morphine tablets to avoid being forcefully repatriated to France by Nazi officials. The Arcades project remains his most extensive unfinished work, yet even in this permanently adolescent state, it begs for conversation and response. The work reads to me like a secret diary of an anthropologist in the underworld—full of wit and mystery. Within this realm lurks Benjamin’s writings on phantasmagoria. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, this term described a method of optical illusions cast by magic lantern, shadow puppetry, and a theater of specters for entertainment. Benjamin applied the phrase more broadly to the visual culture of the arcades, the spectacle of the market, and to the commodification of artwork. In my own work, I use illustration to communicate magic, myth, and story, much like the illusionary theater of Benjamin’s era.

I am a prose writer and artist of hybrid mediums, namely of graphic literature, and I often find my own artistic practice reflected in Benjamin’s body of work. He sampled and experimented constantly with genre and style, and he moved fluidly between journalism, poetry, criticism, and fiction. I particularly love his lists, marginalia, and open-ended meditations. His archival processes align with my own; I have long been inclined toward a type of autoethnography, as Benjamin seems to have been aiming for with his careful record of thoughts, dreams, cities inhabited, and philosophical musings. Similarly, I maintain a detailed record of my life in various forms: blueprints for imaginary homes, a daily journal dating back to age eight with illustrations and text entries, and lists of everything from early memories to peculiar names on gravestones. I am also drawn to this style of hybrid note-taking as a reader of contemporary graphic novels and comics.

© Frances Cannon

© Frances Cannon

I resonate with texts that reveal the author’s archival research process, particularly autobiographical comics such as Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, which both include visual representations of ephemera from the artists’ pasts; Bechdel’s graphic memoir includes illustrations of her old journal entries, photographs, to-do lists, reading lists, and letters, and Satrapi’s graphic memoir includes sketches of her dreams, newspaper clippings, and even news events on television that she witnessed as a child. I aim to build a bridge between my reflexive process and Benjamin’s, and the most appropriate form for this bridge to take is a visual journal of fragments which I have collected from his oeuvre: a graphic archive of his poetic clutter, an illustrated record of my reading of his work, a sketchbook I kept during an ambling walk through the labyrinthine museum which he built to house his thoughts.

Benjamin’s alternate temporality calls for a nonlinear and unexpected response to his work, work which is intricately embroidered with anecdote and image. This has been my approach—to wander through his works, collecting, taking my own notes in response to his prose, and then returning to illuminate fragments of his writing. This process, in a way, is my nod to Benjamin’s collection of cultural ephemera, but with added critical and poetic marginalia, as well as graphic illumination. I strive to acknowledge the past and the present simultaneously, as Benjamin suggests is necessary to emphasize the “now-time” over “empty time.” Perhaps by sifting through Benjamin’s work and applying my artistic eye to his theories and writings, I can render an image of the “glamour” of his leaping tiger. I strive to breathe imagistic graphic life into Benjamin’s essays, which already burst forth with dreamscapes, spirits, latent images, and works of art. Through my graphic translations, I want to represent to the contemporary reader a diverse portrait of Benjamin.

© Frances Cannon

© Frances Cannon

My pen wanders a nonlinear path through his catalogue of miscellany. I stroll through his text, embodying his archetype of the flâneur—observer, detective, journalist, and participant. I have physically retraced Benjamin’s steps on my own visits to the subterranean markets of Paris, where I too have fallen under the spell of nostalgic clutter.

My project has been to illuminate excerpts from Benjamin’s essays, his dream journals, the Arcades project, and his short fiction—both his finished and unfinished writings. By weaving my own creative rendering in with his prose, I see this process as an unusual form of graphic translation. I’m decoding his prose into my own personal creative language, which involves further fragmentation and visual elaboration. My primary artistic method is akin to a creative hoarding—assembling quotes, sketches, and images to then sort, curate, and reconstruct. Though my chaos is nowhere near as elegant as Benjamin’s, my drawings and poetic fragments are attempts to echo his notes; an artist’s phantasmagorical tribute to his wandering eye. My drawings and curation of fragmented texts reflect the spirit I see in his collection.

© Frances Cannon

© Frances Cannon

Throughout the process of engaging with Benjamin’s work in image, I have held in mind Hélène Cixous’s essay “Without End, No, State of Drawingness, No, Rather: The Executioner’s Taking Off,” from her book of theory and art criticism, Stigmata . This essay has been important for me to keep in mind while I attempt to translate Benjamin’s work into the visual realm. Even the title communicates Cixous’s hesitation, revision, and creative power. So, the “No, Rather” in the title is more than appropriate: the essay is a work in progress, a stream-of-consciousness display of the mind on the page. This essay embodies the linguistic origins of the word “essay,” taken from the French essayer , or “to try,” inasmuch as Cixous tries out multiple arguments and philosophical concepts as she writes.

She writes beautifully about the line shared by both word and image—the line that functions both in word and image, the drawn line, the tentative line of a handwritten letter, the doodle, the sketch, the chicken scratch in the margins of a book. Cixous begins in a confessional, personal tone, exposing the intimacies of her artistic doubt, but she soon expands beyond herself into an intertextual, intercultural exchange of ideas. She starts by writing about her own work, “I just wrote this sentence, but before this sentence, I wrote a hundred others, which I’ve suppressed, because the moment for cutting short had arrived”; but soon she moves into an admiration of Kafka and Dostoevsky, and soon after this, leaps into an abstracted discussion of “Good” and “Evil” in artmaking. Already we get a sense of her argument without a single identifiable thesis. She rambles, ambles, wanders from thought to thought, and yet, that is the thesis—her very wandering. She is trying to prove to us through her syntactical style—her aimlessness—that the essence of artmaking and writing is the expedition itself. Artists should remove our grip on an end goal and instead focus on the process.

© Frances Cannon

© Frances Cannon

Cixous emphasizes the importance of trial and error, and that so-called mistakes—such as the errors that might occur during translation—are essential to this process. Error signals progress itself. Her appreciation of the natural creative mutation which occurs during translation reminded me throughout my work on this project that I am not merely illustrating Benjamin’s sentences; rather, I collect ideas within his prose and release them into a new form. I am translating his concepts into a parallel language—one of image, texture, visualized dreamscape, and figuration. I read between his lines and weave lines of my own using his textual template.

I have kept another literary compass on my desk during this process: a favorite text from my childhood, The Dot and the Line , written and illustrated by Norton Juster, who also wrote The Phantom Tollbooth. In this concise, graphic narrative, a “romance in lower mathematics” is told simply through linework. The line is a character, who performs diverse tricks and twists to communicate emotion and philosophy. Juster’s line as character allows me to approach Benjamin’s work with a little humor, for the daunting task of translating the work of a literary genius requires a hint of levity.

__________________________________

From Walter Benjamin Reimagined: A Graphic Translation of Poetry, Prose, Aphorisms & Dreams. Used with the permission of the publisher, The MIT Press. Preface and illustrations copyright © 2019 by Frances Cannon.

Frances Cannon

Frances Cannon is a writer and artist. She is the author and illustrator of the graphic memoir The Highs and Lows of Shapeshift Ma and Big-Little Frank and has published several other books of poems, translations, and artworks. She teaches creative writing at Champlain College in Burlington, Vermont and the Shelburne Craft School in Shelburne, Vermont. She received an MFA in Creative Nonfiction Writing from the Iowa Writer's Workshop. See her website at https://frankyfrancescannon.com.