Ilhan Omar on Her Early Days Getting Out the Vote

The Roots of a Rising Political Star

I was nauseous and hungry, tired and cold. But time was running out, so even though I wanted to go home, put my feet up, and eat Thanksgiving leftovers, I returned to the elevator bank and pressed the button to go up.

In the two months that I had been doing get-out-the-vote work for Mohamud Noor’s bid for Minnesota state senator from the 59th district in a special election, I had been to the Riverside Plaza apartment complex more times than I could count. Some of the mostly Somali residents were surprised when a pregnant hijabi knocked on their door and wouldn’t leave until she had convinced them to vote for Noor in the Democratic primary on December 6, 2011. Or at least vote.

I hadn’t been home from Africa long and was already pregnant with Ilwad when I threw myself into the campaign that ignited me and many others seeking progressive representation to bring about economic prosperity and opportunity for all of Minneapolis’s residents.

Noor—a Somali immigrant, a former employee of the state’s Department of Human Services, and a political newcomer—was running against Kari Dziedzic, a policy aide to the county commissioner and daughter of legendary longtime Minneapolis city council member Walt Dziedzic. Carrying on a political family dynasty, Dziedzic was pushed by the Democratic establishment while Noor, running to become the first Somali in the country elected to a higher office, was of the people. At least that’s what I thought and what I was willing to work for.

Noor’s run for a seat on the state legislature was the first campaign I volunteered for after returning from North Dakota, but I had been involved in many forms of community organizing way before that.

My interest in the workings of our democracy began a few years after I arrived in the United States, when Baba asked if I would accompany him to a caucus. He had heard about the gathering in an English class he was taking at a local resource center. Understanding it to be some manner of participating in democracy, he was interested in attending and wanted me to make sure he was able to follow along with what was being said and done.

Neither of us had ever been to anything like it. Our first introduction to the event were the people hawking their candidates outside, trying to get passersby to come into the venue like carnival barkers for public policy.

I was able to translate the words for Baba, but I couldn’t make sense of the process. At first people were just sitting around, and then, without any kind of proper introduction, someone eventually started talking, only to be cut off by someone else yelling, “That’s not how you do it!” A little later, an agenda was handed out about issues to be discussed. Then people began to argue about the agenda. I don’t remember the candidates, but the room was filled with a lot of characters. It was a good place for people watching.

Even though the whole thing was messy—really messy—it was clear that everyone was eager to be there. As much as they were screaming at one another, there was a passion for the process that even I, then a 14-year-old, could appreciate. No one voice was more important than any other at the caucus—anyone who showed up could participate to their fullest.

That seminal event stayed with me not only because Baba and I continued to attend caucuses together. Seeing democracy in action at the caucus was what convinced me of the power of the vote. It’s the cornerstone of our system. Everything else builds from that one act.

My studies in political science and my efforts organizing volunteers for campaigns and causes only solidified this viewpoint. It was always my belief that the first, most important step was to get people to vote—not because of a specific issue they felt strongly about but simply because it’s our right. My mission in my canvassing work was to help people understand that it should be an honor to cast your ballot.

Seeing democracy in action at the caucus was what convinced me of the power of the vote. Everything else builds from that one act.I disagree with those who argue that educating voters on the issues or candidates is crucial to the process. Worrying who is going to vote and why is an afterthought, a privilege. In the United States, one of the greatest democracies in the world, we have one of the lowest voter turn-outs, which is a disaster and a disgrace. I can express the importance of voting succinctly. It is not something that needs a long explanation. We vote because it’s a right enshrined in our Constitution, and one that we must exercise.

I brought this message to hundreds of residents during Noor’s two-month campaign for the state senate. Ultimately, he didn’t win. But we put up a very good fight. In a five-person race, Dziedzic—who had raised the most money and had the most support from elected officials and unions—beat Noor by only six points. As the Star Tribune reported, “His second-place finish was marked by a dramatic turnout from the city’s Somali community.” Ninety-five percent of voters in the heavily Somali precinct surrounding the Riverside Plaza apartment complex cast their ballots. “No other precinct turned out more voters,” the newspaper added.

As it turned out, Dziedzic became one of Minnesota’s greatest senators. There’s a narrative around a politician and then there is reality. As someone who worked hard for her opponent, lived in her district, and served along-side her, I’m uniquely qualified to say I was wrong when I thought she wouldn’t be a true representative of the people. Sometimes the terms liberal and progressive are not rooted in work and efficacy but in the people affirming them. When Dziedzic won, we didn’t expect her to engage the community. But her ability to do just that and to advocate for policy change has been tremendous. The fact that her campaign against Noor had been so rigorous and close might have also helped shape what kind of senator she ended up being. Where once she might have been persuaded to adopt the status quo, she now had to serve a district that wasn’t going to settle for that.

*

After I returned to Minneapolis with my college degree, I did what I had done when I had arrived at NDSU—I just signed up for everything and anything in the progressive movement that piqued my interest. I joined the board of many progressive nonprofits and was involved with a political action committee that did work in the new American community to get politicians to care about our issues. I was also elected the vice chair of an organized body of volunteers for my senate district, which Dziedzic had won.

I was everywhere, although I was never the person out in front. My name wasn’t on the agendas or the billboards bearing policy initiatives; I didn’t offer comments for the paper on community meetings. I was a behind-the-scenes busybody. Unafraid of confrontation, I was sent to meetings to upset people and hold them accountable. But I also planned rallies and chaired conventions. I joined Minnesota Young Democrats and made resolution recommendations at the state central committee. I am the kind of person who truly enjoys spending ten hours on a Saturday talking through the party platform.

If there was a need, I showed up—with or without permission. People would often ask me, “In what capacity are you here?”

“Why does that matter?” I would answer. “I’m here.”

I always thought it odd when people created obstacles for themselves that got in the way of addressing an issue or being in a certain space. My guiding principle was “Do I care enough?” If so, then I didn’t care what anyone else thought about my presence in a room or conversation.

In 2012, the Republicans, who had a majority in the state legislature at the time, drafted two ballot measures: one was to require photo ID for voters, and the other one was to define marriage as between one man and one woman in the Minnesota constitution. I immediately jumped in to get the vote out against the two referendums.

“Be Nice, Vote No Twice,” the grassroots campaign against the two constitutional amendments, was exciting for me because I got to speak about my love for democracy and voting.

Although the voter ID measure predominantly affected people of color, as all laws aimed at voter suppression do, it wasn’t the not-so-subtle racism of the proposed amendment that had me fired up. My primary objection was bigger than that. It went back to the idea that voting is the right of any American. You don’t need to pass a test, understand what you’re voting for, or have a license. If you are a citizen, you get to vote. It’s as simple as that. The state Democratic Party, running the advocacy against these ballot measures, determined the overall messaging of the campaign. The immediate issue we faced as the grassroots volunteers charged with implementing the centralized message was that our community members didn’t necessarily respond to the conventional narrative the campaign had put forth.

The argument the campaign put forward against the photo ID measure revolved around access obstacles to obtaining driver’s licenses. Perhaps in other communities or other states, it is hard for people to obtain a driver’s license. Not in Minneapolis, where whether you were white, Latino, African American, East African, or a student at the university, the barrier to getting an ID was pretty low. The Department of Motor Vehicles is centrally located and accessible by public transport. And the cost is low. So the campaign’s argument just wasn’t the right approach for our community.

The statewide mandated narrative against the marriage equality ban was modeled after President Barack Obama’s nationwide campaign. It encouraged people to connect and share their stories about LGBTQ friends and loved ones. In many of our marginalized communities, the conversation around “I’m your friend. I’m your son. And because I am, you should support my right to marry who I want” wouldn’t resonate.

I felt it was my responsibility to figure out the right narrative and the right tools for when we reached out to our districts. Because I knew what would work with me, I was confident I knew it would work with the people around me. Tailoring a centralized directive to each community is the task of those on the ground in a huge grassroots effort like this was.

The winning narrative—that these measures threatened freedom and civil liberties—wound up speaking not only to communities of color in Minneapolis but also to white rural Minnesotans. For greater Minnesota and more conservative rural regions, the argument was if you vote yes, you’re infringing upon people’s rights by changing the constitution, which is intended to protect freedoms. Voting no, however, means nothing changes. For urban and immigrant populations, the same idea based on the importance of preserving freedom was slightly modified: if today they come for one community, such as same-sex couples, who’s to say they won’t come for another community, like yours, in the future?

This clever and clear messaging that worked everywhere was driven by values-based organizing. We didn’t try to change how people felt. Instead, by explaining that the amendments threatened freedom and civil liberties, we activated citizens to vote based on their core values.

The result was a defeat of both ballot measures. This was no small feat, as no amendment defining marriage as between one man and one woman had ever been defeated on the ballot in the United States before. Minnesota became the first in a string of states that later defeated similar proposals, paving the way to the legalization of same-sex marriage in all fifty states three years later. The groundswell of organizing made 2012 a ridiculously good year for progressive Minnesota. Democrats, who already occupied the governor’s office, took back the House and the Senate as well that year.

__________________________________

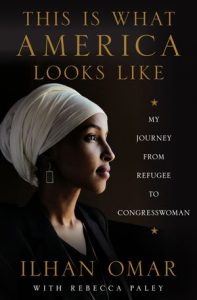

Excerpted from This is What America Looks Like by Ilhan Omar. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins.