Ignoble: On the Trail of Peter Handke’s Bosnian Illusions

John Erik Riley Takes the Long Road to Srebrenica

Maybe life is a process of trading hopes for memories.

–William T. Vollmann, The Rifles

*

When Peter Handke was announced as a Nobel laureate, my mental state was one of disquiet and déjà vu. I knew what we were heading for because I had seen the same narrative develop before, albeit on a smaller, not quite so international scale. In the spring of 2014, Peter Handke was awarded the International Ibsen Prize for his work and invited to a ceremony in Oslo in October. The debate that unfolded in Norway seemed to take the well-meaning jury by surprise. They were decidedly unprepared for the furor, most of which concerned itself not with Handke’s drama, but with a handful of essays about the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Articles for and against the prize appeared in every major newspaper, and intellectuals engaged in online exchanges in the early morning and far into the night. I found myself among the latter group, on what many deemed the anti-prize flank of the discussion, and chose Facebook and Twitter as my fora for discussion. Several of my updates were later published in Handke-debatten (The Handke Debate), a 679-page volume which collects essays, op-eds and ephemera about Handke’s texts about the Balkan wars—particularly A Journey to the Rivers—and serves as both documentation and analysis. Contributors include historians, political activists and many of the country’s more prominent critics and writers. To anyone following the discussion about the Nobel decision, Handke-debatten reads like a premonition of what was to come.

For a relatively small—but increasingly vocal—part of Norwegian society, the breakup of Yugoslavia remained a collective trauma, 20 years after the signing of the Dayton accords. The effect on public discourse was explosive. Although Handke’s writings about the Bosnian war were—in the context of his oeuvre—rather minor works, they were brought to the forefront. There were demonstrations and protests, and demands that the prize be revoked. On the day of the awards ceremony, Handke was called a fascist by a small group of chanting Bosnians, and he returned the favor by exclaiming “may the mouse fuck you.” There was little room for nuance, to say the least. Much like the country that fell apart in the early 1990s, the literary world was balkanized. Status updates defined the new front lines. Facebook “likes” were rhetorical weapons.

That most famous of Norwegians, Karl Ove Knausgård, also participated in the debate, both as an avid Handke reader and the author’s publisher. Although his contributions are curiously absent from Handke-debatten, they are emblematic of the force and direction of the exchange. Although many platitudes were written about the value of art and freedom of speech, few critics and writers seemed interested in immersing themselves in post-war forensic reports and court judgements. Only a minority of the participants had actually visited the places Handke describes in his travel writing. I was no better myself. Although I had been to Bosnia-Herzegovina several times and knew my fair share of war history, I had yet to visit the mountainous regions to the East. Višegrad and Srebrenica were still words on the page to me. They were images on a screen, fragments of second-hand stories and reports.

Beneath the ornate and intricate linguistic workings of Handke’s text, one can hear the rumbles of some of the worst tendencies of our present age, which have, in recent years, been amplified to a fierce din.

So when the debate eventually subsided—from what I could tell, out of a sense of collective exhaustion—I made a decision. If I got the chance, I would go to Bosnia-Herzegovina, where I had been before, but head east this time, to the places Handke visited in the mid- to late-90s. Along the way, and after, I would read and reread—and re-reread—his most contentious texts. At the time, the idea was more akin to an odd hobby; it was the stuff that bad road movies are made of. But then, as it happened, my mother and I started talking about taking a trip together, and Sarajevo was mentioned. I asked her if she would want to visit Eastern Bosnia, as well, and she assented. I booked flights, places to stay, a rental car. Then I brushed the dust off my edition of Handke’s travel writing.

What would happen if I read and reread his postwar and wartime work in the context of the landscape he once visited? What could I learn about writing—and about literature and politics—by traveling in his footsteps, more than two decades after the fact?

*

My mother and I flew from OSL to SJJ on a Monday in July 2019, in a plane full of the usual suspects for a summer trip to Bosnia-Herzegovina.

We were joined by the occasional backpacker, a businessperson or two, airline employees on leave. But more than anything, we were surrounded by ex-Yugo expats heading home for vacation. Years ago, during the war, Bosnians were given special refugee status and allowed to retain both citizenships, at the time an uncommon practice in Norway. Later, economic incentives were put in place for people to return to their homeland. But why do so when your homeland is an economic ruin, with an employment rate far up in the double digits? Add to this the Bosnian ability to retain many cultural identities at once, and you are left with a bunch of people living in refutation of Ibsen’s commandment that one should not live “by pieces and in part.” Like characters out of a book by Aleksandar Hemon—and like the Yugoslavia that once was—they are comfortable being several things at once.

Once we were off the plane, old and new was on display, war-usurped families reunited for the summer on the one hand, tourists driven by new-found wealth on the other. What was immediately apparent to us was the Middle Eastern influence on Sarajevo. Families of bearded men in shorts and T-shirts and veiled women in black niqabs moved through the airport in groups. Or they stood in line waiting for rental cars. There was a carefree nature to the way they moved that is often absent among native Bosnians. Like many visitors with money, they behaved with a form of entitlement, not unlike the American tourists I have often observed in Norway. In the midst of the various groups in the arrivals area, crisscrossing my field of vision, I eventually spotted an old friend who was waiting to drive us to the hotel. She waved, helped us across the street and into her car.

All photos by the author.

All photos by the author.

The tone and content of the conversation that followed was familiar to me. As we followed curvy roads along and across the Serb neighborhood of Lukavica, we were presented with every Bosnian problem under the sun, be it private or public. Her husband was severely ill. Her son was in trouble at school. The government was a mess, the medical system didn’t function, and they were strapped for money, both at home and at work. How do you get by in a country with a dysfunctional economy and very little money? My sense of empathy grew along the way, and when we finally arrived, her car parked at an impossible angle to the curb, I offered to pay for the ride. Or at least let me pay for gas, I insisted. But her hospitality and pride would have nothing of it. Come on! she yelled amicably. Come on! At least join us for dinner, I asked. She thanked us graciously, but had to attend to her husband.

What would happen if I read and reread his postwar and wartime work in the context of the landscape he once visited? What could I learn by traveling in his footsteps?

We hugged, and she left us in the company of an old friend of mine, a man I had met during my first trip to Sarajevo in 2000. After my mother and I had dropped off our bags, we all walked to a restaurant in a side street in the nearby Turkish quarter. Over Sarajevsko beer and Bosnian delights, in between storytelling and catching up, there was time to discuss the route I had set up for the next few days. I wanted to know what he thought and if he could offer us any tips or ideas. We would go to Goražde first, then Višegrad, crossing into Serbia and the Mokra Gora national park. Then, we would go to Bajina Bašta, one of the border towns Handke describes in his work. Upon returning to Bosnia, we would drive to Srebrenica and Potočari and then to Sarajevo by way of Olovo. My friend’s face changed a bit as I spoke. It gradually dawned on me that I had performed a rookie mistake, strolled right into the minefield of geography and politics. In all honesty, I should have known better.

My friend had little to offer in the way of travel tips to Srebrenica. His occupation is, in part, to get various groups to work together, across ethnic lines. Although his sympathies are clearly on the side of the victims—that is, all victims—politics make overt support of this or that issue difficult. Some of his clients would frown on a trip to the memorial in Potočari. If he had visited the place, he had done so briefly and invisibly. On the subject of Mokra Gora, however, he waxed lyrical about the beauty of the place. You will love it there, he said. “The mind can, how to put it … breathe?” Conversation turned to other subjects, flowed the way conversations should. We exchanged stories about the war, about food and music, about life in Norway—which my friend had visited—then and now. I also asked him about the conditions of this road and that road along the way.

As my mother and I walked back to the hotel in the summer heat, I could tell that she was working hard to take it all in. Sarajevo is a safe place to visit, but one rarely leaves the place unmoved. Although she had done her best to prepare for the trip, read her fair share of books and seen a number of documentaries about the war, meeting the reality of history first hand—observing its manifold effects—was something else entirely. I sometimes call the accompanying state of mind Ideological Claustrophobia. Every event and object can be interpreted in a variety of ways, depending on who you are speaking to. Nothing is benign in Bosnia. Everything is political.

*

In the days that followed, my mother and I explored Sarajevo, sometimes together, sometimes alone. During breaks, at cafés and restaurants and in my hotel room, I spent time scanning newspaper op-eds and status updates from 2014, and paged through documentation from the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). I also reread Handke’s most famous pieces about the Bosnian war, which have been collected in the volume Jugoslavia: Tre reiser (Yugoslavia: Three Journeys), published by Karl Ove Knausgård’s independent press, Pelikanen.

Knausgård was already Handke’s publisher before 2014, and he was one of the author’s staunchest supporters both during and after the debate. Three Journeys was released a year later and includes Handke’s infamous essay about the time he spent in Vojvodina and Western Serbia (in the United States, this particular text is entitled A Journey to the Rivers: Justice for Serbia). The Norwegian volume is expanded to a triptych, in which Journey is filled out on either side and further contextualized. The opener is a misty essay about the breakup of Yugoslavia, full of handkesque nostalgia and longing. The third text is an essay about Handke’s travels in Eastern Bosnia in the summer of 1996, and should be read as a comment to—and extension of—A Journey... It was written in the wake of controversy and is clearly an attempt to set the record straight.

Every event and object can be interpreted in a variety of ways, depending on who you are speaking to. Nothing is benign in Bosnia. Everything is political.

Pelikanen is a fine publishing house, and should be lauded for making Handke’s more controversial texts available in Norwegian, at what I suspect is a monetary loss. They are necessary reading for anyone interested in the subject of Handke, the former Yugoslavia, and the murky waters where aesthetic and political currents meet. Unfortunately—as is the case in 2019, after the Nobel Prize announcement—many people during the Norwegian Handke debate of 2014 avoided reading the author’s travel pieces altogether. This led to quite a few misunderstandings and a fair share of unenlightened outbursts and pompous posing. One prominent intellectual, William Nygaard, then head of PEN Norway and former head of Aschehoug, went so far as to say that Handke had placed himself “outside the boundaries of freedom of speech.” A renowned political scientist compared Handke to Goebbels.

Accusations such as these—reactions based not on actual source material but general impressions—made things easier for Knausgård. Debaters inadvertently tossed the author a ball or two, and all he needed do was dunk. Knausgård’s response to the freedom of speech question was a clinical dissection of his opponents’ arguments. He picked them apart, laid the parts on the table, and the debate could easily have ended there—with embarrassment. It is the writer’s right, even duty, to ask uncomfortable questions, according to Knausgård. Handke asks uncomfortable questions, therefore he has fulfilled his duty. Whether we, the readers, agree or disagree with his viewpoint in the end is another matter entirely. So far, so good. Nygaard apologized. Unfortunately, Knausgård chose to go further still, so far as to defend Handke’s specific approach to the topic at hand.

For Knausgård and many of his supporters, Handke’s subtle literary method is of particular value; that is, it adds something to our understanding of the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina that is otherwise lacking. His language is inherently “human, humanistic, anti-fascist and anti-totalitarian,” according to Knausgård; this should be immediately apparent to anyone who reads his work. When it comes to much of Handke’s production, I am inclined to agree with Knausgård. With regard to A Journey to the Rivers, however, I remain dumbfounded; I find it hard to grasp that he and I have read the same material. When he reads Handke’s depictions of Bosnia-Herzegovina, he sees a literary master who is ever inquisitive and also knowledgeable, whereas I see an artist with a propensity towards doubt who has been led astray by his own inclinations and idiosyncrasies.

The paradoxes become even more evident when Knausgård writes about Handke’s appearance at Slobodan Milošević’s funeral, a well-established point of contention in the debate. Although he does not explicitly endorse Handke’s statements, Knausgård claims that Handke is “merely doing what an author should do, ask questions.” He thereby sidesteps an uncomfortable topic, which is how the context of words often alters their meaning. The funeral of a former autocrat, in a place brimming with nationalists—many of whom have likely committed war crimes—is just such a word-bending context, if ever there was one. In that volatile space, written and spoken language run the risk of being subordinated by the language of the body. Handke’s physical presence is of greater meaning than his rarefied thoughts and any insistence that he “lacks answers.”

The image of his body onstage says: This man is deserving of my support. Ambiguities are eradicated.

*

After breakfast, my mother and I checked out of our hotel and—after a ridiculously circuitous search for our rental car location (you got to love Balkan logistics!)—found our way to E761 and headed east. In Sarajevo, the sun was still bright and the temperature was oppressively hot, so much so that it was hard to avoid a certain… crankiness. As the altitude increased, though, the number on the dashboard readout dropped, and my attitude improved. We are Norwegians, mountain people. The cooler the air, the lighter the mood.

In Goražde, my mother sat at a café and drank coffee at a table near the river, with a view of the nearby mosque, while I took time to explore the bridge. For readers of recent Bosnian history—and any fan of Joe Sacco’s graphic novel Safe Area: Goražde—this area is familiar. During the siege of Goražde, a corridor of sorts was constructed, so that people were able to move from one side to the other, hopefully unscathed. The bridge above protected the bridge below. Since then, a plaque has been mounted to commemorate local ingenuity, and the original bridge has been reconstructed and revamped. Goražde is remarkable for other reasons, as well. After the war, it was the only major Muslim enclave to be included in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Srebrenica is, in fact, located in Republika Srpska). On the map, the area immediately surrounding Goražde resembles the proverbial sore thumb.

One prominent intellectual went so far as to say that Handke had placed himself “outside the boundaries of freedom of speech.” A renowned political scientist compared Handke to Goebbels.

When I returned to the café, my mother asked about the bridge, and I found that I was beginning to withhold information. My mother is far from weak. She is, in a way, a child of war, born just after the liberation of Norway in 1945. Her home was not lacking in stories about the workings of the Nazi regime and how they affected members of her family, many of whom were imprisoned. Despite this, I could tell that recent war history—by which I mean that particular Bosnian variation on civil war brutality—was starting to weigh on her. There is something uniquely terrible about the conflicts in the Balkans, the ways in which it pitted colleague against colleague, brother against brother. Nationalists left little room for multifaceted Yugo-identities the likes of which there were many.

The gloom and dread I often feel is often complicated by a form of second grade survivor’s guilt, a feeling that I am delving into problems that do not belong to me. My wife and I often talk about this at home when she has returned from a research trip in the region. She is a peace researcher with wartime rape as her field of expertise. Yet she and I are merely visitors to the Bosnian narrative. Their horrors are not ours. Our grief—when it is there—is far easier for us to handle. Usually, inevitably, we come to the conclusion that it is better to care than to not care, and that our curiosity is, after all, rooted in empathy. Yet the grief remains, and with it, the need to decompress, with bad movies, with light conversation, with alcohol (too much of it sometimes!) and with exercise.

But how do you decompress when you are still there, in the mind-bending zone itself? Perhaps with silence, by internalizing the conversation, letting the mind continue on with its own inner monologue. By the time we left Goražde for Višegrad, I was speaking less about the most recent war and more about literature and cultural sites, about the rivers and waterfalls. I talked about the famous stećci, those restored medieval stones and gravesites that dot the landscape in much of the Western Balkans. I hoped to show her some prime examples, that were hopefully marble white and full of impressive engravings. But before that, I wanted to show her the famous Mehmed Paša Sokolović bridge, so we parked in a small slot on the northwestern side of the Drina, just below some impressive green hills.

*

Peter Handke describes Višegrad in his second travel piece about the war, the so-called “summer addition,” which is clearly written by a man under considerable pressure. Not only had his initial “winter journey” been met with heavy criticism from authors and journalists. He had not yet achieved one of his central goals, which was to visit the sites of the worst wartime massacres in recent memory. In A Journey to the Rivers, Handke and his friends are stopped near the border to Bosnia-Herzegovina and forced to turn back.

Handke knows how to use an anticlimax, however; it is one of the things he does best. The first travel report ends with rarefied introspection about the complexity of Serbia, the dignity of the people and the necessity of doubt. His text is not a j’accuse in the vein of Zola, he claims, but something else entirely. “I am merely driven towards justice. Or perhaps only by doubt, the need for balance.” The text is also full of pondering queries and sensory impressions; the author seems to be working hard to discern aspects of reality that lie beyond the realm of logic and proof. This can lead to some odd—and eerily insensitive—depictions of wartime events. One of his many rhetorical techniques is to criticize photographs of civilians. He picks them apart, detail by detail, even going so far as to suggest that the victims have posed for the camera in certain ways to underscore their suffering.

The media lens distorts the world, but the genius author sees things more clearly. Or so Handke would have us believe. Despite this mix of skepticism and confidence, however, he had yet to “sense” Srebrenica and “perceive” Eastern Bosnia. He had not seen the post-war region with his own eyes, except from afar. Given the value that he places on estheticized observation and sensory cognizance, I suspect that this particular failing must have irked him.

In 1991, over 60 percent of residents in the Višegrad municipality were Bosniaks. In 2019, the number is under 10 percent.

So a new, additional trip became necessary. Written in the same subjective and searching style as the “winter journey,” the “summer addition” from 1996 is often interpreted as a far more open and nuanced offering. For doesn’t Handke acknowledge there that the Srebrenica massacre was reprehensible? And does he not yearn to see a map of Europe with Srebrenica in the middle, so that the events will never be forgotten? The claim seems to be that his essays work in ways that are vastly divergent from journalism (see the Swedish Academy’s statements and op-eds for example). They must also be read in conjunction with one another, as a whole; and in the “summer addition” Handke shows that he is deeply compassionate about everyone who suffered during the war. To this, I can only reply that I disagree.

The way I see it, the “summer addition” is the worst of the two texts, ethically speaking.

*

The sun was bright as my mother and I crossed the bridge, and there were boats on the river, ferrying tourists back and forth between various sites. When the vessels reached the support beams, they slowed down, perhaps so that people could be given ample time to photograph the span, capture it in all its glory. An absurd proposition indeed! Even on the far end, which we reached after a short walk, my 16mm lens—which is wide on a full frame camera—was too narrow, and I could only see fragments in the viewfinder, cutouts of the bridge’s greatness. This architectural wonder was best viewed with human rather than digital eyes, only then did it glow impressively, only then was it possible to take in the stonework, the arches and all the other ingenious details.

The Mehmed Paša Sokolović bridge was designed by Mimar Sinan in the 16th century and completed in 1577, when the region was under Ottoman rule. The more common association these days is to Ivo Andrić, the ex-Yugo-region’s only Nobel laureate in literature. In his most famous novel, The Bridge on the Drina, Mimar Sinan’s masterpiece is transformed into a symbol of empire, of interethnic relations and brutality through the ages. It represents hope and despair, love and loss. One generation’s political power is echoed by a later generation’s suffering. During the 1990s, the novel was often read by journalists and reviewers as prophecy, and as a precise diagnosis of Western Balkan mentality and culture. On the cover of my copy at home, a blurb specifically states that one must read Andrić if one wishes to understand the war in Bosnia.

The Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad features in Ivo Andric’s novel and was the site of many massacres in 1992.

The Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad features in Ivo Andric’s novel and was the site of many massacres in 1992.

Anyone can be turned into a mascot, however, and such is the case with Andrić. When we reached the other side of the bridge, my mother and I found an Andrić bust and an Andrić bench. We also found buttons and, on the wall of a nearby abandoned building, some very impressive Andrić graffiti. I wouldn’t have been surprised to see Andrić sausages, Andrić cereal and Andrić coffee mugs. The great author and his work has been reduced to a literary Mickey Mouse figure. He has also—it should be mentioned—become the centerpiece for nearby Andrićgrad, the filmmaker Emir Kusturica’s gigantic and megalomaniac valentine to all things Serbian, from St. Sava to Nikola Tesla. The literary-cultural Disneyland is visible from the bridge and includes a cinema and newly built examples of traditional architecture. At the end of a promontory, where the Drina and Rzaz meet, is a Serbian Orthodox church.

As we took in the sights around us, a young man, presumably a Bosnian Serb, strolled over to us, and I used the opportunity to ask him about an abandoned building nearby. He smiled and replied with typical Bosnian sarcasm: “The only thing I know is that it doesn’t work, like most things in this country.” He then laughed and asked if we would want to join a river cruise, and we politely declined, explaining that we had other sites on the itinerary. One of them was a large Muslim cemetery stretching upwards on a hill, lined by a small, dark forest. As we walked back to the car, I found myself repeatedly opening my mouth and then shutting it again, soundlessly. My tongue felt dry. One part of me wanted to talk about what had happened here in 1992, describe it in detail. Another part could barely stomach the thought and was incapable of articulating anything meaningful.

*

Here are some of the facts that I did not talk about while my mother and I were exploring the bridge and its environs (in the presence of tour guides, Andrić souvenirs, zip lines, river cruises, etc.):

In 1992, according to the ICTY, Milan Lukić, a Bosnian Serb, commanded troops and paramilitaries in Višegrad, with extended help from his cousin Sredoje Lukić and their friend Mitas Vasiljević. The men established concentration camps in warehouses and factories, and a rape camp at the nearby Vilina Vlas hotel. During their reign, they either executed or facilitated the execution of between 2,000 and 3,000 Bosnians, most of them Muslim and at least 119 of them children. Lukić’s groups had a particular fondness for sadism and violent theatrics. This included slitting the throats of civilians and throwing them off the bridge, shooting randomly at them with automatic weapons and slaughtering children in front of their family members. Women at Vilina Vlas, both old and young, were repeatedly raped, often under threat of death.

Like all writers, though, Handke has his blind spots and partialities.

Perhaps the worst atrocities in this particular circle of wartime hell, however, were the arson murders in the summer of 1992. On the Serbian Orthodox holiday of Vidovdan, Lukić and his compatriots rounded up civilians and locked them in the bottom floor of a house on Pionirska Street. They then threw a grenade in, killing some of the victims, before lighting the entire room on fire, burning their captives to death. At least 59 people died in the blaze. The massacre must have seemed like a success to the sadists, for like overeager children, they chose to repeat the affair two weeks later, this time in nearby Bikavac. Around 70 people were rounded up, stripped of valuables, then burned alive. There were at least 60 deaths. According to one witness to these events, the cries of the victims were like nothing she had ever heard, and could only be compared to the “screams of cats.”

The Muslim population quickly learned that it was best to flee. In 1991, over 60 percent of residents in the Višegrad municipality were Bosniaks. In 2019, the number is under 10 percent. Fortunately, some of the victims managed to survive to tell their tale to journalists and peacekeepers. Their testimonies were later instrumental in the conviction of Milan Lukić to 30 years in prison. But history is also a question of what is visible in the landscape, and destroying the evidence after the trial is a way of whitewashing the past. So there have been repeated attempts to expropriate the Pionirska Street house to expand a nearby road. The site has since been purchased with private funds. The only way to stem demolition, it seems, was to renovate the building into a livable residence. In Bosnia, everything is give and take, especially if you find yourself among the victims.

People who wish to memorialize the past are forced to alter it forever, in this case by transforming the scene of a genocide into a renovated home. No matter your anger, you must acquiesce, in ways large or small.

*

Had Handke been more interested in historical actualities, he could have written a powerful and important piece about the crimes of Lukić and Vasiljević. He could have turned his attention to the fire in Pionirska house, investigated the aftermath in his own unique way. He is one of the greatest writers in the world, with a devotion to detail that is often startling and enlightening. Even when he writes about something very specific and particular—like his own mother’s suicide in A Sorrow Beyond Dreams—his words are expansive; they encompass manifold aspects of human experience:

Horror is something perfectly natural: the mind’s emptiness. A thought is taking shape, then suddenly notices that there is nothing more to think. Whereupon it crashes to the ground like a figure in a comic strip who suddenly realizes that he has been walking on air.

Much of what I appreciate about Handke’s writing is evident in this brief quote. In it I see: (1) an inclination towards philosophical speculation that, for any number of reasons, never feels impersonal, (2) an enticing mix of ponderous curiosity and sudden shifts in tone and (3) that near-comical way his language mirrors what it is describing (the sentence implodes at just the right moment, as the comic strip character descends). Like all writers, though, Handke has his blind spots and partialities. When he is faced with something like Višegrad, his anger and skepticism get the best of him. One example among many can be found in his insistent nitpicking of an article by Chris Hedges that the New York Times published in 1996. “Witnesses said,” Handke repeats, “survivors said,” in a sarcastic tone, like a comedian imitating the voice of someone he wishes to mock.

Here, as elsewhere, Handke’s antipathy is not merely political in nature; it is aesthetically motivated. The language of the mass media is as much of an affront to him as the facts themselves. When Hedges closes his article with a witness who repeats “the bridge, the bridge, the bridge”—admittedly, with great pathos—Handke brushes it off as too melodramatic, too much like Tennessee Williams. Similarly, when Handke joins a Serbian vigil in a cemetery in the hills (he does not, in the interest of balance, visit an equivalent Muslim gathering), he is pleased to observe that the people around him weep with dignity. They do not wail or moan like mourners in more Southern climes. Although Handke is quick to add that grief is the same all over the world—the text is such that he always has a rhetorical escape route—the suggestive tone of the passage is strangely cold and critical.

When faced with Višegrad, Handke’s strengths become limitations, in part because of how he chooses to employ his undeniable talents. What could have been a lovely and particularized depiction of mournful individuals is transformed—in the course of a paragraph—into something more akin to an accusation. Remember, dear widows, to mourn in a dignified way! Do not raise your voice, lest the great genius disapprove of you! And please note that if a photographer shows up, you must behave in a manner that will not seem conspiratorial in hindsight. Pose with calm, and do not, by any means, scream or prostrate yourself in the wake of unimaginable horrors. If you have been raped and tortured, speak of your rape and torture in hushed tones and in closed rooms. If you have lost a family member, drink plum brandy, sing softly and remain serene.

There are many forms of genocide denial.

There are many forms of genocide denial. The most obvious kind is overt and unambiguous (“These things didn’t happen.”). Alternatively, denial can be portrayed as an attempt at balancing the scales, thereby diminishing the severity of the worst crimes and their systematic nature (“Everyone was misbehaving. Mistakes were made on all sides.”). These rhetorical tactics, although common and influential, are easy to pick apart. The most complex forms of denial are far less blatant, however. On the surface, they do not resemble denial at all, but are more like a perpetuum mobile of incredulity, of doubt feeding on itself. The author may pose questions under the guise of being inquisitive, even when the questions have been answered and the answers are indisputable. Uncertainty and hesitation are transformed into semantic devices. (“I am merely asking questions! What do you have against questions?”)

Handke’s texts about Bosnia are probing and inquisitive. In a later op-ed—best described as a sort of “Handke for Dummies”—Knausgård praised the author’s insistence on immediate “first-hand experience.” Not only is he distrustful of second-hand accounts; his writing is such that he is constantly searching for things that normally go unnoticed. Thus, we often find him describing garbage along the side of the road or the lighting and dust in a room. Small stories are blown up and expanded upon; large stories are moved to the margins. For certain avid Handke readers, his poetic prose is inherently enlightening. When he avoids certain aspects of reality and focuses on others, he is trying to open up our intellects and illuminate our minds. He is expressing empathy for all things large and small, reminding us of details that we refuse to see or that the mass media would have us forget.

To a careful reader, however, one who is sensitive to the history of the region, Handke’s pieces about the war in Bosnia are hard to justify. I, for one, am not easily swayed by the empathy he expresses for the victims in Srebrenica, although his sense of horror at times seems heartfelt. Nor am I convinced by his suggestion that Muslims had fine lives in Višegrad after the war, despite Handke’s assurance that he observed a man in a fez at a soccer game (!). A literary text is composed of disparate parts, and must be judged not only by the content of these dissimilar details, but by the sum of them—by what they, viewed together, seem to express. In the case of Handke’s “winter journey” and “summer addition,” I can’t help but notice that the author spends a lot of time condemning the news media and criticizing photographs when he could be doing something else entirely.

At a Muslim cemetery near Višegrad.

At a Muslim cemetery near Višegrad.

For someone who attaches so much value to direct phenomenology, Handke is surprisingly unwilling to open himself up to events and stories that might disturb or surprise him. This is at its most obvious when he, towards the end of the “summer addition,” finally visits Srebrenica and is in the presence of potential war criminals. (He does not mention names, merely states that one of the men he speaks with is on the “Hague list.”) I do not object to Handke speaking with some of the worst people among us, if that is, indeed, necessary for his work. A great writer, with the appropriate methodology, chosen with care, can provide us with knowledge about evil that might escape us when reading court documents, forensic reports and judgements. What bothers me is the cumulative effect, how his work does little to help us see more clearly, and instead ends up obscuring reality.

One of the strangest images in his book is relayed in a vision he has, at the very end of the volume, of “freedom fighters” on the hills. In a series of insistent questions, Handke—ever the film buff—proposes that we may one day compare the forces in Eastern Bosnia to “Indian tribes” in Hollywood westerns. For do we not often see “Indians” on the hills in movies, as well? And do they not attack caravans and kill “peaceful Americans” in the name of freedom? I’m not sure what is worse here, the bizarre comparison itself or Handke’s overzealous symbolic appropriation. In any case, as an attempt to grapple with some of the worst atrocities in modern day Europe, comparing Native Americans—who were themselves victims of genocide—to authoritarian aggressors remains a peculiar choice indeed. As a metaphor for Srebrenica, it fails miserably.

*

When confronted with criticisms such as these, Handke’s reactions have been of two sorts. Years ago, he usually had the disposition to double down. They do not read my work, he would insist; they do not understand its complexity, its radical subjectivity and particularity. (Some of the members of the Nobel committee seem to follow this line of thinking: that Handke’s literary approach to the war is superior to other forms of language.) In recent years, the author has been far less interested in dialog and more inclined to release curt statements, seeking to underscore his innocence. In them, he insists that he has never doubted the severity of the events in Srebrenica. He has yet to comment on his depictions of Višegrad in hindsight, however, and reassess his initial impressions and opinions.

A great writer, with the appropriate methodology, chosen with care, can provide us with knowledge about evil that might escape us when reading court documents, forensic reports and judgements.

When reading Handke, I often find myself thinking about another writer, one who is equally iconoclastic, but far more democratic in his approach. In works such as Rising Up and Rising Down and Poor People, William T. Vollmann presents the reader with depictions of all sorts of brutality, and he does his best to speak to people on all sides of a given conflict. Only after he has meticulously gathered the facts, does he make his subjective judgements. I can agree or disagree with the result, but I rarely get the feeling that he doubts the well documented accounts of witnesses or turns his back on the content of a verifiable photograph. Vollmann’s war writing can be frightening, but it is also enlightened and clear-sighted; Handke’s resembles a fever dream, and is therefore frightening. It is frightening, in part, because his writing, his language is so insistent, so incantatory, so hard to resist.

Transgressions are often committed with the best of intentions, and artifice can mask misguided assumptions. Beneath the ornate and intricate linguistic workings of Handke’s text, one can hear the rumbles of some of the worst tendencies of our present age, which have, in recent years, been amplified to a fierce din. To Handke, the New York Times and Frankfurter Allgemaine Zeitung are fake news. There are fine people on both sides of the war. Sound familiar? There are, of course, good people of all ethnicities in Bosnia, but Handke muddles the point when he mixes the military “sides” with ethical or moral ones. From one perspective—that of soldiers in battle, say—there were, indeed, Croatian, Serbian and Bosniak “sides.” From another perspective, however, there were two sides, that of neofascist nationalism on the one hand and transethnic values on the other. For someone who believes that he is supporting the latter tendency, Handke is eerily comfortable around purveyors of the former.

Under the title of Handke’s A Journey to the Rivers we find these words: “Justice for Serbia.” Not the Serbian people, mind you, but the Yugoslav Republic, which at the time was being led by the autocrat Slobodan Milošević. Although war crimes were committed by all ethnicities, as evidenced by the ICTY, no regime did more to stoke the nationalist fires than Milošević and his war criminal lackeys in Eastern Bosnia. The ethnic cleansing of the region during the Bosnian war was of a degree and level of brutality unmatched by other regimes. When Handke decides to defend the “Serbs,” as he sees them, he overlooks that many of those same people were opposed to Milošević and the crimes committed in their name. Willingly or unwittingly, Handke subscribes to the same logic that made the war itself possible. He promotes a fallacy: equates the individual—one to one—with the state.

Any critique of the state must, according to this logic, be understood as an indictment of an entire population. But this brand of all-sidesism downplays the fact that many Bosnians and Serbs had loyalties that were located elsewhere; they were not fueled by violent nationalism, but were working to ensure that nationalism didn’t swallow everything in its wake. When Handke chose to speak at Milošević’s funeral, he was not supporting “the Serbs” per se; instead, he had become entangled in that particular strain of late-century Serbian tyranny which led to the slaughter of thousands. Whatever complexities he sought to preserve, in his eulogy and in his writing, were drowned out by war drums and the shrieks of the “undignified” mourners. I do not know if Handke was merely bleary-eyed and confused or a cynic and an opportunist at the time. But his errors speak volumes.

*

My mother and I continued on our journey through the borderlands, and in hindsight, what happened after our walk on the bridge is something of a blur. I recall events, but they are not always connected or in chronological order. Or: When they are connected, the connections come from my mind rather than from the world itself. I float in the vast space of memory, grasping for wire and string.

I remember that we parked outside Andrićgrad, and strolled about the courtyards. Emir Kusturica’s megalomaniac Serbian Disneyland was a tourist trap, full of ice cream shops, cute cafés and sculptures of famous Serbians. It was clearly not designed with outsiders in mind and eerily cool and quiet, like a restaurant with only a few tables filled. The mural above the Cineplex didn’t help to make me feel any more welcome. In it, Kusturica, the Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik, the actor Gerard Depardieu, and the tennis player Novak Đoković play tug of war with an invisible adversary outside the frame. A blonde Vladimir Putin—idealized, younger than his present years—looks on with a benign visage, like a saint blessing the scene. (Welcome to Andrićgrad, friends! Behold a famed oppressor of journalists and the world’s most important Slavic autocrat!)

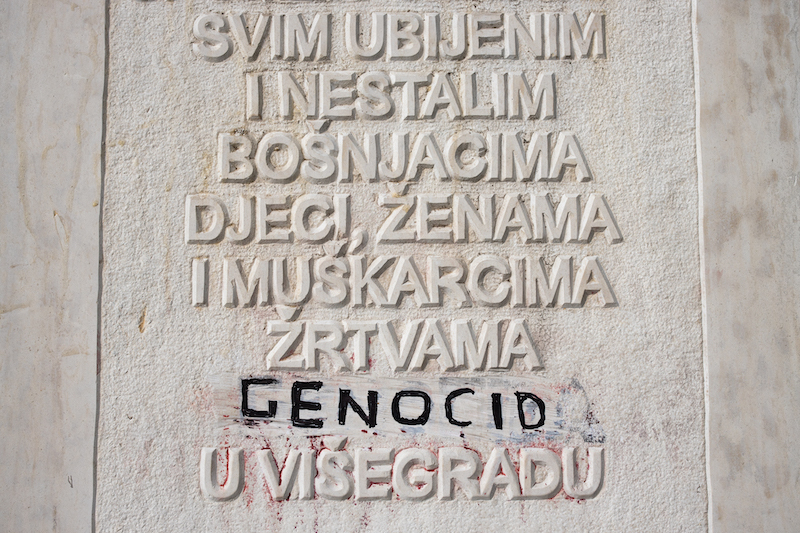

If Andrićgrad was like the scene of a party that was yet to take place, the graves on the north end of Višegrad resembled silent ghosts at attention. I have always considered this particular type of Muslim graveyard, on a hill, visible from afar, to be particularly beautiful. But not all is as it seems. Everything in Bosnia is symbolic, remember? There is always a nit to pick, an ideological fight to be had? Some time ago, a politician—one of Milorad Dodik’s ideological sisters—removed the word “genocide” from an obelisk near the entrance to the cemetery. The police protected her while this happened, according to reports. People still sneak in from time to time and put the word back. With permanent markers, they replace the formerly engraved word, with or without an “a” at the end. It is as though the word can barely be uttered, no less conjugated.

We eventually crossed the border into Mokra Gora, which was full of lovely forests and rivers and rolling green hills. And the mind did, indeed, breathe, up there, as the eagles circled about. We drank wine, we slept, we talked about the farms we had seen, how difficult it must be to be a Serbian farmer in these mountain villages. Then we visited Bajina Bašta, near the border, where Handke had gazed into the river and thought deeply about the passing of time. And we parked near the stećci (medieval tombstones) in Perućac, not far from where forensic investigators once swarmed the riverbanks and excavated evidence of genocide. Unfortunately these stećci were not as lovely as the ones I had once seen in Herzegovina, when I traveled with Alma in 2000 and saw burned-out tanks by the roadside and countless roofless houses. The stones in Perućac were tainted with moss and had a grey-like patina.

To Handke, the New York Times and Frankfurter Allgemaine Zeitung are fake news.

And I thought about time myself, about how close the war seemed back then, at the start of the century, and how far removed it seemed now, like a white stećci peeking out of the grass, a mushroom refusing to rise. I told my mother more over beef soup at a nearby restaurant (again, this feeling of a party waiting for guests, in a virtually empty place). I was overeager, couldn’t stop talking. I spoke of earlier trips to Bosnia, and how they had affected me. I described a mass grave in Sarajevo, just below the hospital, told her about my conversation with the representative of the OHR and how the plastic bags glistened in the sun. I told her about the houses in the hills, full of cigarette smoke, how my wife had interviewed rape victims about their experiences during and after the war. When she came home, she sat in the sofa and wept silently, while a sitcom buzzed on a nearby screen.

I also mentioned the dinners and parties at our house at the turn of the century, how they often vacillated between joy and terror. A Bosnian friend once refused rice porridge, quite suddenly, because it reminded him of the war. A Serb from Kosovo drank too much vodka as she followed the news of the Račak massacre. “Crazy people,” she sometimes muttered, sometimes yelled, as she shook her head in disbelief. “Why are they so CRAZY?” To say that I’m traumatized by events such as these would be an exaggeration, but they often flashed through my mind during the Handke debate of 2014, as they later did on my trip with my mother. The memories of them are akin to small snapshots. Like any photograph, they reorient my attention and recalibrate my mind. Each image provides a glimpse of a larger, more horrifying and perhaps ungraspable world.

A world of remains.

Of relics and monuments.

*

When we were done eating, we returned to the car, rearranged our luggage, collecting much of it into small piles in the back seat—these, too, were monuments in a way, transient memorials to our own journey to the rivers—and then we drove across the border, from Serbia into Bosnia-Herzegovina. The time had finally come for us to visit the memorial and cemetery in Potačari. When we reached the crossing point in the valley, a somewhat ramshackle cluster of offices and shacks, our helpful guard pointed to the right, to the road that led more directly to Sarajevo. We explained that we preferred to take the mountainous route, and he seemed genuinely surprised. But we avoided his insistent recommendations and continued on our way.

The roads got progressively worse as we drove, and there were very few people between Bajina Bašta and Srebrenica. But the hills were often dotted with signs of life, memorials large and small, some of them complete, others more makeshift. We saw Muslim cemeteries surrounded by incomplete concrete prayer areas, and we saw Orthodox churches with flags emblazoned with that idiosyncratic Serbian cross, the small c-shaped curls faced outward like mouths. Along the road, spring faucets had been built or renovated, so that travelers had access to water, often in the oddest of places. The only people we saw were two children on bicycles, who had biked to a nearby shack which we—afterwards, as we sped past—realized functioned as a store. All along the way, I tried to focus on the road, which was never straight, always curvy. Back and forth, back and forth, back and forth…

Leaving Srebrenica.

Leaving Srebrenica.

When you are driving on a twisting and unkempt Bosnian mountain road, a town—any town—will seem like the apex of civilization. It is an oasis in the desert, a warming hut in the snow. So it was with Srebrenica. Despite the history of the place, I was happy to arrive. I enjoyed the sight of cars parked, ready for action, for motion, and of people drinking coffee and laundry hanging to dry. I also recognized certain places from pictures of Handke’s trips in the mid-90s. I saw an apartment building, parts of which had since been fixed up, and I found the spot where Handke once posed next to the name of the town, a yellow sign with letters in Serbian Cyrillic. We filled the tank, bought some water and Coca-Cola, a small snack, and then rolled downward towards the Potačari cemetery. Thousands of white markers poked forth from the valley floor, formed wave-like patterns in the grass.

*

What is there to say about Srebrenica, about Potačari? And how does any of it relate to Handke, to the Ibsen prize and the Nobel prize? When it comes to the awards themselves, I am plagued by a mixture of irritation, anger and apathy. Bosnians have been ignored or given the proverbial finger in so many ways—and for so long—that another misinterpretation or affront seems like par for the course. Back in Sarajevo, when I had described the Norwegian Handke debate to my Bosnian friends, all they did was shrug their shoulders and roll their eyes. They’d seen it all, heard it all, before. That said, I remain dumbfounded by the many attempts—by the Swedish Academy, by some of the brightest authors and critics I know—to downplay the content of Handke’s travel writing from Bosnia. Why grasp at tiny straws of sensitivity and wisdom when the general current of the texts is all too evident?

To me, the positive evaluations of Three Journeys are reminders of the dangers of ideology. No aesthetic approach is, by definition, naturally and unequivocally ethical and humanistic. Intricate language and Socratic questions can often help us; they can reveal things which would otherwise be ignored. But they can also function as smokescreens. This seemed like an important lesson to remember on this particular afternoon in Bosnia. I was reminded of the date by a friend and colleague who published Handke-debatten and who, like me, is both Norwegian and American. My mother and I hadn’t had cell service for a while, but in Potačari it returned, and a small message popped up on the screen wishing my a happy 4th of July. On the other side of the ocean, in the United States, people were either asleep in their beds or just waking up to prepare for Independence Day celebrations.

The ethnic cleansing of the region during the Bosnian war was of a degree and level of brutality unmatched by other regimes.

We eventually found the entrance and parked between a pair of buses which seemed to be without passengers. My mother put on a headscarf she had brought for the occasion, and then we parted ways, choosing to walk about and reflect in solitude.

*

I walked past a prayer area, studied the list of names for a while and a stone marked with a number, 8372, followed by an ellipsis, an indication, perhaps, that the dead were still being counted. All of this was more or less as expected and corresponded to photographs that I had seen in books and studied on the internet.

The people I observed were in groups, for the most part, and something about the way they behaved made me think that they were expatriated Bosnians on vacation. They were also secular in dress, with only headscarves or hijabs as obvious religious markers (the upper middle class niqab-clad tourists were nowhere to be seen). I began to feel self-conscious about my own clothing and manner: the cargo pants, the running shoes, the multi-pocketed travel shirt. I was carrying two cameras as I walked, one dangled from each shoulder, and I felt ashamed for having brought them. Although I believe that my intentions were good—I wanted merely to learn and to pay my respects, at long last, after all these years—I both looked and felt like a tourist. But then I saw that everyone else was carrying cameras as well. At one point, a family came across what I presume must have been the final resting place of a relative. Various groups posed in turn, as portraits were captured.

For a moment, I felt vindicated. But then I remembered that this was their place, their horror and struggle, and I felt ashamed again. I wanted to turn around and go back to the car, yet retreating also seemed wrong. It was terribly hot now, the temperature was at its worst so far, far worse than in Sarajevo, and the air was humid. A hazy glare seemed to emanate from the objects around me, and there were dark clouds in the distance. I could occasionally hear distant rumbling, perhaps from an oncoming storm. I eventually reached the apex of the graveyard, a small amphitheater of sorts, where the markers were placed in semicircular patterns. White marble glistened in the valley, stung my retina, and I was forced to squint. Ghostly green floaters shaped like the markers hovered above the scene, pointed upwards at the sky. I sat down on a bench, and the hot stone burned my thighs through my pants.

Eventually, the floaters dissipated, and I turned my head to observe more of my surroundings. I noticed a green metal fence along the graveyard perimeter, behind which was a farmhouse with chickens and sheep grazing. Life still unfolded there. Further down, on a different outskirt of the cemetery, newly dug holes gaped in the grass. The July commemoration of the genocide was a little more than a week away. Twenty-four years after their murders the dead were still being buried, and funerals would soon be taking place. Several of these ceremonies would likely transpire at the very edge of the site, beyond the original designated area. From my vantage point, I couldn’t help but think that the number of dead seemed to challenge the imagination of the planners. They had designed a cemetery that turned out to be too small and had to redraw the map as the years went be.

My gaze eventually returned to the family I had observed before; the group of eager photographers who had just completed a short prayer and were walking in single file between the graves. They came closer to me, then passed. For a moment I thought about my friends in Sarajevo. I got the urge to run over and talk to them, befriend the man in tan pants and the woman with the pink hijab and the cute little children waving their arms around. But how? What could I possibly I say? How could I start a conversation in a place like this? The family gradually reached an area in the middle of the cemetery, a gathering point with a metal roof and carpets and speakers and a microphone, then walked past the pylons and through the prayer area. I blinked for a moment, and they disappeared from view. Once again, I was alone among thousands of stones.

In their absence, my eyes focused on a marker under a tree that seemed to break with the general pattern in the cemetery. Upon closer inspection, I discovered that it was the final resting place of a Catholic Croat who was murdered in the Srebrenica massacre. His mother had this to say about the grave, according to a website about the cemetery and visitor center: “They asked me if I wanted him to be buried elsewhere because this is mainly a Muslim graveyard. [But] he died with them. Let him rest with them.” For me, facts like this one—like many of the stories I come across when I travel in Bosnia—are imbued with deeper meaning than Handke’s rarefied language and his harangues about the media. A Catholic gravestone in a Muslim cemetery is a manifestation of interethnic wisdom and solidarity, reveals real world nuances that the author of Three Journeys obscures or ignores.

*

One of my strongest memories from our trip is not one of nuance, however. Instead, it is blatantly symbolic, almost comically so. On our way back to Sarajevo, during our descent from Olovo and into yet another valley, my mother and I narrowly avoided death.

We had driven in silence for quite some time, over a mountain pass and past Olovo. To say that we were melancholy would be an understatement. Since it was July 4th, I found myself in a state of regret, not about the trip itself, but the fact that we were not with the rest of our family. Although I am not one for blatant statements of nationalism, I see the value in celebrating a nation of many, a nation that is inclusive of all ethnicities and colors and creeds. What would have been better, then, to gather people in our garden in Oslo, to commemorate this idea. But I also knew that the idea I wanted to celebrate was presently under threat, in part thanks to the president himself, who daily says and tweets vile things about people I appreciate and love. Hateful rhetoric is no longer breaking news; it has become routine.

I chose to visit Srebrenica, in part, to pay my respects and to learn a thing or two. But also to remember. My wife and I—and our Bosnian friends—often talk about why remembering is necessary, and one of our reasons, among many, is that the wars of the 90s were more than just a terrible fluke in the stream of history. Today, they also seem like a warning of what is to come. Not only do many white nationalists view Milošević’s warlords as heroes; not only do they admire the ethnic cleansing of Bosnia, so much so that the song “Remove Kebab” has become a rallying cry. The line between dignity and brutality is rapidly deteriorating. We live in an age of ideological division and rising authoritarianism, and much of what I see is an echo of our recent past. I fear for myself and my children, as I fear for the future of Europe and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

As I was thinking about all of this—turning it over in my mind, as we swerved back and forth on yet another twisted Bosnian road—a car pulled out from behind a truck in the opposite lane and barreled towards us as though we were nothing but air. With seconds to react, I pulled into a gravelly pocket by the roadside and hit the brakes. Our luggage in the backseat—my cameras, bottles of water, fruit, maps, etc.—was hurled forward and landed with a series of splats and thuds onto the floor. I throttled the motor, and then hopped out of the parked car and stood there for a moment, looking around and trying to catch my breath. The car that had nearly decimated us continued upwards into the mountains without so much as a honk. Then more vehicles whizzed by. The hum of traffic continued. Life returned to normal, unfolding unceasingly, as it does, with or without us.

Are you okay, my mother asked, and placed herself next to me. Below us, a stream flowed. Weeds and plastic bags waved in the water. Yes, I replied. Yes. We were lucky this time.

John Erik Riley

John Erik Riley is an author and publisher in Oslo, Norway. His own work includes the novel Heimdal, California and the essay collection/travelogue Øynene i ørkenen (The Eyes in the Desert), about online culture and surveillance mentality. He presently works as the managing editor for Norwegian fiction and poetry at Cappelen Damm, Norway’s largest publishing house.