If Watergate Happened Now, It Would Stay a Secret

Sy Hersh Reveals a 1970s Washington That Seemed to Contain... Decency?

I had one thing going for me as I slunk into the Watergate scandal. It came off a tip I had received a month or two earlier but had ignored. A friend from the New York publishing world told me that a freelance writer named Andrew St. George, who had ties to the anti-Castro Cuban community in Miami, was circulating a book outline about the experience of Frank A. Sturgis, one of the five men who had been caught burglarizing the Democratic National Committee offices in Washington.

My initial response had been, more or less, “What does this have to do with the war in Vietnam?” Now, given my new assignment, I began calling around to get a copy of the outline. One of St. George’s most explosive claims, based on what he said were a series of interviews with Sturgis, was that Sturgis had done political surveillance of Democrats in Washington as well as being part of a team that was investigating drug trafficking in Central America. I wondered whether investigating meant smuggling. All of this allegedly was done at the direction of Howard Hunt, a former CIA officer who was linked to the Watergate break-in team. St. George’s reputation in the New York publishing world was spotty, but he had won prizes in the late 1950s for his photographs of the Cuban revolution and apparently had gotten a contract, for minimal money, for a book based on interviews with Sturgis. I called him and we had a meeting at which it became clear that the likable St. George was extremely eager for me to write a story about his book project. I told him that would never happen unless he could produce Sturgis for me and prove that the two had the relationship he claimed.

After an introductory meeting with the two, I met with Sturgis the following day. He confirmed that he and others on the Watergate break-in team had been paid hush money since their arrest. He had wanted more money and did not get it, which was the sole reason, so I surmised, he had talked to St. George and was now talking to me. I returned to Washington knowing that Andrew St. George would be mad as hell at me, and he had a right to be, but I had the beginning of what could be a hell of a story. I also had information to barter with the lawyer who was representing Sturgis and his break-in colleagues as well as the Feds in the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Washington who were prosecuting the case.

Sturgis had told me he thought John N. Mitchell, Nixon’s attorney general, had knowledge of earlier political dirty tricks targeted at the Democrats, which included spying, or attempts to spy, in 1971 on Senators George McGovern and Edmund Muskie, then the leading candidates for the Democratic nomination. I learned later, not from Sturgis, that $900,000, far more money than was previously known, could not be accounted for by Nixon’s 1972 reelection committee. There was no proof, but there also was no question in my mind that some of the unaccounted-for money had ended up, through cutouts, in the hands of the break-in team.

My new information was consolidated into one long piece that ran on Sunday, January 14, 1973, with a modest headline on the left side of the front page. I had used the word “source” repeatedly throughout the story, without identifying who the sources were. Of course my editor at the Times, Abe Rosenthal, knew their names, but I insisted on being as opaque in print as possible; this was just the first step up a big hill, and I wanted everyone involved in that first story to keep on talking.

“The Senate Watergate Committee was voted into being in early February by an ominous, for the White House, vote of 77 to 0.”

One of the first calls I got on Monday morning was from Bob Woodward. We had never met or talked, but he congratulated me and thanked me for doing the story. The Post could not do it alone, Bob said, and he knew he needed the Times with them. Nixon’s landslide reelection, despite the brilliant work he and Carl Bernstein had done, obviously rankled. I’ve liked and respected Bob ever since, although we differ on many issues. He did not have to make that call.

There was no lawsuit from John Mitchell or anyone, and I sensed—as I was pretty sure Abe did, too—that there would be none as I kept on going. I focused over the next few months on learning what I could about the White House and the men who ran it, and I had a few long talks with senior Republican Party insiders who supported Nixon politically but were fearful of what he might have done. The Senate Watergate Committee was voted into being in early February by an ominous, for the White House, vote of 77 to 0, after which I was able to make useful contact with a few senior senators and staff, Democrat and Republican. I was trying to find truth in a White House sodden with lies, deception, and fear. Being the New York Times guy on the beat surely helped—no other newspaper in America had its authority—but it was still Bob and Carl’s story.

I got to where I needed to be by mid-April, in terms of contacts inside the Nixon White House, Congress, and the agencies doing the investigation into Watergate. From April 19 to July 1, I published 42 articles in the Times, all of them dealing with exclusive information moving the needle closer to the President, and all but two of them on the front page. The high point was in early May; in six days I wrote four stories that led the paper with banner headlines and a fifth that was the off lead—the front-page story at the top of the far-left column. Reviewing them in the past few years reminded me how half-nuts I must have been with exhaustion and anxiety and lack of sleep. On May 2 it was a three-deck banner headline saying, “Watergate Investigators Link Cover-Up to High White House Aides and Mitchell.” A subhead said, “6 May Be Indicted.” On May 3 it was a three-deck headline reading, “Investigators Term G.O.P. Spying a Widespread Attempt to Insure Weak Democratic Nominee in 1972.” On May 5 my off-lead dispatch linked a senior Nixon attorney to the destruction of campaign data. On May 6, I brought CIA wrongdoing onto the front page; there was a three-column headline that day saying, “C.I.A. Officials Summoned to Explain Agency’s Role in Ellsberg Break-In Plot.” On May 7 there was another three-column headline: “Marine Corps Head Linked to C.I.A.’s Authorization for Ellsberg Burglary.”

*

It was an unimaginable explosion of news as Nixon was being fed to the wolves by his friends and enemies. Amazingly, it all took place before the existence of the White House taping system was known. It was nirvana for me, marked by halcyon days without second-guessing by editors in Washington or New York. I also felt I was responding, in a totally appropriate and professional way, to Nixon’s cavalier attitude toward the My Lai massacre, his support of Lieutenant William Calley, and his unwillingness to protect General Jack Lavelle, whose sin was doing what he had been ordered by the President to do. The national desk in New York, and its editor, David Jones, became my best friends. I would be called midday by someone on the desk in New York and asked if I thought I would have a story for that day. If the answer was yes, I would be asked if it was front-page material. I always said yes, of course.

It was, in those months, a self-perpetuating process. I was getting stories because I was finding and writing stories, and people inside the government or Congress with something they thought important or pertinent to say wanted to talk to me. It was inevitable that I would end up in close contact with the honorable men in that disgraced administration; for example, I could reach Elliot Richardson or one of his senior deputies whenever I needed in the month or so after Richardson’s appointment as attorney general.

“It was an unimaginable explosion of news as Nixon was being fed to the wolves by his friends and enemies.”

There is a story behind my contact with Richardson that I have not told, until now. After his reelection in 1972, Nixon nominated a White House aide named Egil Krogh to be undersecretary of transportation. It was a big leap for a 33-year-old aide who lacked any experience in transportation issues; he was known only as someone who had worked on drug abuse and internal security issues for John Ehrlichman. I made an appointment to visit Krogh before the full Senate had scheduled a vote on his confirmation. He was still at work in the White House, and my pretext was the international drug issue; Krogh and a colleague, a former aide to Kissinger named David Young, had traveled to Southeast Asia in late 1972 to ask questions, and we talked about that. I asked a bunch of leading questions but came away thinking that there was no hidden agenda in Bud, as he was known; he seemed to be earnest but unhappy.

Then, one day in the spring of 1973, Krogh telephoned me at the Times. He had a problem and wondered if I would meet him at the office of a lawyer named William Treadwell in downtown Washington. Treadwell turned out to be a prominent member of the Christian Science Church in the Washington area, and Krogh, as a committed member of the faith, had turned to Treadwell for guidance. Krogh explained that he had a crisis of conscience because he had not told me the truth when we met earlier and, after consultation with Treadwell, it had been determined that he could absolve himself by doing so now. So, on a bright sunny day in late April, or early May, I was stunned by what he told me—that he and David Young had been members of a secret internal security group in the White House, known formally, as I learned later, as the Special Investigations Unit, and informally as the Plumbers, that in 1971 recruited G. Gordon Liddy, a former FBI agent, and E. Howard Hunt, a former CIA operative, to assemble a trusted team to do whatever was needed—provided there would be no link to the White House—to find out what else Daniel Ellsberg knew that could be damaging to Nixon’s reelection. What the Hunt-Liddy team did, of course, was break into the office of Ellsberg’s psychoanalyst in Los Angeles. The two men later orchestrated the famed Watergate break-in in June 1972. Krogh told me that he was also going to confess all to federal prosecutors and asked that I not write about our conversation until he had done so. With that understanding, I agreed to treat his absolution as a private matter between him and me, as the person he wronged, in front of a representative of his church. His goal was to free himself from his burden that, as Pertschuk saw, was tormenting him. After my hour or two with him and Treadwell, I knew that the emerging Watergate scandal was going to get much darker, as did Bud Krogh. He subsequently did agree to cooperate with federal prosecutors and spent four and a half months in jail after being given a two-to four-year sentence for his role in the Los Angeles break-in.

I honored my agreement with Krogh, but I did privately relay much of what I learned to an aide to Richardson soon after Nixon appointed him attorney general in May 1973. Richardson had been given the job by Nixon, so I assumed, with the understanding that he would protect the President and Kissinger from the hell that was coming their way. I have no idea whether the information I relayed was useful, but Richardson and I talked many times, always on background, during the next year or two.

He understood early, as I did, that Watergate was going to get much uglier.

![]()

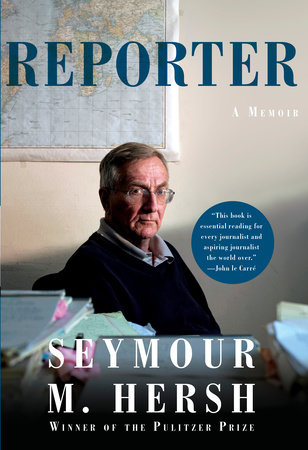

From Seymour M. Hersh’s Reporter, courtesy Knopf. Copyright Seymour M. Hersh, 2018.

Seymour M. Hersh

Seymour M. Hersh has been a staff writer for The New Yorker and The New York Times. He established himself at the forefront of investigative journalism in 1970 when he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his exposé of the massacre in My Lai, Vietnam. Since then he has received the George Polk Award five times, the National Magazine Award for Public Interest twice, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the George Orwell Award, and dozens of other awards. He lives in Washington, D.C.