If Reality TV is Superficial, Why Does It Make Me Feel So Much?

"I Don’t Have the Confidence to Call What I Love Bad and Still Love It"

In The New Yorker, Kelefa Sanneh once wrote that reality TV is the television of television. I think that’s a nice way to put it—the one thing that remains universally low in a medium that, for the first half century of its existence was the face of low culture. Now my university offers lectures called “Game of Thrones and Philosophy.” Netflix sitcoms apparently provide a submersion in some valuable critique of the way we live now. And beyond TV: Pop music is written about like revolution. Treacly Super Bowl ads are shared as short films.

This is not a new observation, I know, and I don’t mean to be crotchety—this is all a good thing, if sometimes annoyingly self-congratulatory. There’s liberation in the freedom of low culture from the muck of its implications. But, amid the self-celebrating demolition of cultural hierarchy, there’s also a little comfort in the notion that something remains less-than, still forcing a consumer to face the worst implications of their tastes, and therefore maybe themselves.

British scholar Annette Hill analyzed survey responses to TV consumption patterns and traced the way reality TV conversations took on the language and habits of addiction. Participants lied about what they watched—surprisingly small percentages of self-avowed TV fans would admit to watching shows whose ratings suggested a runaway hit. And the honest responders often adopted the tone of an addict’s confession, a sheepish exploration of the compulsive—I don’t know. I thought it was actually rubbish . . . but I was so hooked.

Apologetic viewing, Hill called it.

Again, it seems impossible to ignore that the shame is part of the form. After all, we who consume are part of the interaction—it’s the people who produce the stars, the stars, and then it’s us. Everyone is a little disappointed, a little embarrassed, yet still we return to what is both comfortable and not. We have to see ourselves returning each time, have to ask ourselves why. Have to ask ourselves if there’s something better out there to aspire to for those people on display, for us.

In an episode of the latest season of Sister Wives, TLC’s drama about a clan of likable, progressive-seeming polygamists driven from their Utah homestead to set up camp in a stucco cul-de-sac in suburban Las Vegas, the family holds a meeting. These meetings play a central role in nearly every episode. Some involve just the wives, some the husband and the wives; some include everyone—20-some-odd humans of various sizes sprawled across one living-room floor.

“Everyone is a little disappointed, a little embarrassed, yet still we return to what is both comfortable and not.”

In this recent episode, Kody and all four wives sit around one of their dining room tables. They’re having a conversation about a family party in honor of Kody’s official adoption of Robyn’s children from a previous marriage. This is a growing-the-family meeting, the most important kind, but also it’s a meeting about food. All families, after all, must eat.

The camera enters the shot like a guest entering the home, lingering over a painted sign in the foyer, with the words Together We Make a Family followed by the names of every family member somehow squeezed in. At first husband and wives are seen at a distance. Light fills all the windows so that they’re opaque, so that there’s no outside. The house appears strangely unlived-in, and this is common—in a show that, as much as anything, is about the constant, crushing, joyful presence of children, when children are absent from a scene there is no evidence of them ever existing. Some recliners and a leather sofa sit empty in the living room. The floors are clean, like they’ve been prepared for company.

Every spouse has a notepad on the table. Kody is in his usual denim button-up shirt, no undershirt, chest skin winking out. His hair is long, wavy, and blond. It seems like he may color it in service of his boyishness and laid-back dudeness, which is in service of the central drama of the show, the question of how such blandly normal, generally easygoing Americans could participate in such an ancient taboo.

Kody is talking about chicken. He says the wives are making salads, right, and so he’ll take care of the meat—he’s going to pick up killer, sauce-dripping wings. He seems pleased with himself. Robyn cuts him off, and the camera turns to her. She says that chicken wings were not at all what they’d talked about. Kody interrupts and says he hasn’t even ordered yet, chill out, and Robyn’s head pulls back because of how quickly his voice turned nasty. Kody’s tensed now, shoulders up a little, forearms flexing under his denim. Robyn continues to say that she wants a Sunday-dinner feel, this is a formal thing, a celebration, white tablecloths, nice napkins, and plus they’re all trying to be healthier, and how on earth would barbecue wings fit into this vision—which, again, she has already articulated to Kody?

Another wife chimes in to say, No wings, no drumsticks, let’s leave it at that. Then she looks at Kody, grins, and says, This must be eating you alive inside. All the wives are grinning now.

Kody looks tired. He says that he’s not disagreeing with anybody, he’s just trying to help figure this out. Just ease up, he says to Robyn, and pushes his palms out over the table in the universal stop sign. Everyone stops, but they’re still grinning. The camera scans over all the faces, with the neon sunlight clouding the windows behind them, in the family room of their impossibly clean, nondescript home. My God, how many shows have we seen where people mill around in a house just like theirs? It never looks better, it never looks worse; it never looks lived-in, but that’s the only thing it’s meant to be: a place where we believe a family might live. And their family is just like all the other families, except not at all like them. And, man, a chicken dinner is hard to organize. And, man, a life of any kind is hard to sustain.

Look, I’ll buy all the critiques about the unrepentant superficiality of reality television the moment someone looks like shit in a fictional show. I’m thinking specifically now of The Leftovers, which, I get it, is brilliant in a lot of ways, and is about pain and loss and the attempt to believe that you may be a redeemable person even when the universe seems orchestrated to make you believe that you aren’t. Heavy stuff. Interior kind of stuff. But all I think about when I watch it is the unacknowledged exterior. I mean, these people look incredible. And it goes beyond genetic fortune—these people are goddamn sculpted, and I never see a scene of any one of them doing that sculpting. They stress-eat a lot, and drink. The only character who exercises jogs a little and stops mid-jog to smoke. And not to make this all about me, but I’ve been jogging quite a bit lately and my obliques don’t look like his do, and really the only reason I don’t smoke anymore, beyond solidarity with your quitting efforts, is because it would slow down my jogging, and this fucking guy casually jogs and smokes his way through the apocalypse and I’m supposed to focus on his mental breakdown?

“What I’m saying is that if the superficial and the interior are diametrically opposed, how come the superficial makes me feel so damn much?”

Give me Kim Kardashian’s droning on about her baby-weight fears; give me televised body augmentations and the bruised, bandaged after-scenes when a still-drugged star claims to feel more confident already. Give me Jax, on Vanderpump Rules, only drinking hard liquor for the reduced carbs and then forcing himself to face the gym as a near-middle-aged man with a permahangover, living up to the only obligation that he seems to consider important. Give me Kody and the wives at the grocery store, buying chicken in bulk, back home in lumpy sweatshirts, chewing, making small talk about needing a spa day, something indulgent, they deserve it.

They are alive and looked at, willfully, resentfully. It’s a constant, high-pitched swell of strings, an unspoken panic that I recognize and believe. What I’m saying is that if the superficial and the interior are diametrically opposed, how come the superficial makes me feel so damn much?

Yesterday, screen muted, I was reading Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, and I thought I had an epiphany on this one line of hers: Bad art makes the viewer much more active. . . . Bad characters invite invention.

Jesus, how many attempts has it taken me to try and fail to say that?

There is so much possibility to be found in broad, surfacey characters; so many details waiting to be filled in. The problem is that I don’t have the confidence to call what I love bad and still love it. And I don’t know if I think bad is exactly the right word, but I certainly find it hard to own up to the fact that part of what I love is the total absolution from the feeling that what I’m watching might be too sophisticated for me.

Kraus writes of being a lover of a certain kind of bad art, which offers a transparency into the hopes and desires of the person who made it. That’s the feeling I recognize. That’s the feeling of rawness and power—to look at the surface of what someone is presenting and think you can see the naked self behind that construction, the valley between how they want to be interpreted and what they’re saying. Either way, the viewer gets to take ownership over how she feels about what she’s seeing and why. It’s even more of a rush when the performer doesn’t demand to be called an artist at all—what greater power than to be the one who projects all the meaning onto the work of a stranger who is so thoroughly, transparently desirous.

Sometimes, when I’m watching, my mouth is moving, my whispers on the heels of their words, or maybe on top of them, and it never fails to feel like I’m doing something, or at least like I’ve figured something out.

__________________________________

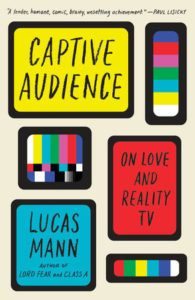

From Captive Audience: On Love and Reality TV. Used with permission of Vintage. Copyright © 2018 by Lucas Mann.

Lucas Mann

Lucas Mann was born in New York City and received his MFA from the University of Iowa. He is the author of Lord Fear and Class A: Baseball in the Middle of Everywhere. His latest book, Captive Audience, will be published in the US by Vintage in May 2018. His essays have appeared in Guernica, BuzzFeed, Slate, and The Kenyon Review, among others. He teaches creative writing at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth and lives in Providence, Rhode Island with his wife.