If Language is a Weapon, Now is the Time to Deploy It

Lydia Millet on the Corruption of Discourse and the

Fight Against Propaganda

In these times, people keep saying. In these times.

They mean different things by it, but they’re all referring to the pandemic. To its uncertainty, confusion, or stasis, for some, its grief or desperation, for others. The chaos that roils at the top of the country and spreads its tentacles everywhere.

I read an essay a few months ago in which a writer indicted language, and in particular English, on a quite reasonable basis: for its global takeover. For its domination and homogenization—for the way in which, as an instrument of imperialist and capitalist ideology, it’s bulldozed other languages beneath it. Continues to do so, as the diversity of languages across the planet, along with its biological diversity, too rapidly declines. English has already driven many smaller languages extinct, taking with them whole cultures and ways of understanding the world.

Other mega-languages have done this too—Mandarin, which has almost as many speakers as English; Hindi and Spanish, which come next in the order of most spoken; French, Standard Arabic, and Bengali—but English stands out as having, by far, the most non-native speakers. Of all English speakers, only one-third claim it as their native language. For comparison, about 82 percent of Mandarin speakers are native.

English is the tongue to which people convert. Or, in the past, were converted by force—here in the United States, through Indian boarding schools that took native children from their parents against their will and whose motto, for a time, was “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

Among the top five spoken languages, only Mandarin isn’t Indo-European. No coincidence, of course: the primacy of Indo-European languages is a direct product of colonialism, since between the 15th and the 20th centuries Europe, which makes up a mere 8 percent of the global land mass, colonized about 80 percent of the planet.

English is far from innocent, in the history of power and subjugation. But, like all languages, it also offers peace, redemption, and surpassing beauty. Access to the hilarious and the sublime. Personally, I love it despite the painful wounds it inflicts and the ugly scars it bears.

*

The capacity of language to change the world is almost infinite. Its weaponization is symbolic and literal alike—happens at all scales, from our daily personal lives to manipulation in politics and trade and advertising to the technology of war. Hate speech, slurs, and subtler and more insidious forms of violence used against us as individuals can shape our relationships to our jobs, to other individuals, to our neighborhoods and communities, and centrally, to ourselves. Some of us, including women and minorities, encounter this more often than others.

What occurs to me, as I sit down to write, is that this is the time to stand up for language.

In the public sphere, the abuse of language for the purposes of the advancement and profit of certain interests over others creates schismatic distortions of reality that pit us against each other and are hobbling, among other things, our efforts to counter existential threats like climate change and species extinction. And presently, our struggle to control the spread of Covid-19.

In warfare it was language that created our species’ most powerful means of destruction: mathematical physics, a language made, like all written languages, of groups of symbols in relationship to each other, was responsible for the invention of the atomic bomb, which could never have been built without it. Nuclear weapons are the children of language. Along with their biological and chemical counterparts. And the computers that now run their systems, which are made of language too.

We weaponize language opportunistically, in the service of desire. Tout ourselves as superior to other animals and forms of life on the basis that we have it and they don’t. (Continue to make this claim even as evidence mounts that many other creatures do have languages and we just don’t happen to speak them yet.) We manipulate it as propaganda and in hostilities over class and gender and race.

In the pandemic and the three years that came before it, Americans have witnessed our heads of state abusing the spoken and written word with a flagrancy and defiance we’d never encountered previously. A systematic, relentless abuse that’s more typically seen in autocratic nations with state-controlled media. In this new landscape, which appears to have been shaped by one man’s megalomania and the credulity of his followers, the language used by our leadership—not only the president but also his acolytes, his staunchest allies in Congress and affiliated actors in the information economy—is no longer deployed as a tool for communicating and sometimes finessing reality, but as a series of full-blown ahistorical and counterfactual fantasies.

We’ve always lived, of course, in an environment of spin, where politicians presented facts selectively and rhetorically to promote their policy agendas. But spin looks like a quaint artifact now, presuming, as it does, an old-fashioned basis in fact. And a coherent relationship between words and actions. The new order offers no basis in fact at all—only a series of infinitely mutable and irrationally constructed fictions, changing from moment to moment, inconsistent even with each other. A constant verbal gaslighting aimed at solidifying and amplifying the leadership’s power. We can’t even say with confidence that the fanciful assertions emanating from the White House aren’t profoundly malevolent, aimed at allowing many thousands of people to sicken and die for the sake of the president’s reelection. When it comes to the edicts of the powerful, we can be certain of almost nothing.

These are hard times for facts and for words, which have been devalued and distorted. A time of betrayal not only of language, but for it. Language is under siege.

For those among us who live by the integrity and authority of the word—including readers and writers, scientists and scholars, doctors and nurses, lawyers and civil servants, and many pastors and rabbis and imams—it’s the corruption of language, in the ongoing insult of our current national life, that is most disorienting. That frustrates us most acutely and seems to tie our hands, leaving us baffled and full of dread. Trapped under a veil of unreality that denies and repels the real, which stretches above and beyond it unseen and unknown, vast as the sky.

*

I’ve been lucky, in these times, not to be sick or jobless. And to have a place to write: a small guesthouse that belongs to my mother and lies a short walk from my own home in the desert. It’s seen better days—its rusting gutters have fallen onto the ground on every side, and its wood trim is rotting. There are packrats that skitter along the margins of the cottage, leaving piles of droppings. Roadrunners to watch as they catch lizards and streak by me comically, hunkered down at a full-out run with the limp lizards in their beaks. Woodpeckers that chirp at me, angry and piercing, defending their nests in tall cacti beside the patio where I sit to write. Rattlesnakes have a habit of popping up out of nowhere: just yesterday I stepped around the corner of the building, starting back to my house in the dark with a flashlight, and came within inches of treading on a sidewinder. He or she chose not to strike, for which I’m grateful.

Our conflation of entertainment with news has led us into a cultural landfill where garbage passes for food.

There’s also a next-door neighbor who yells at his dog, swearing at the animal with strange, sudden brutality. And periodically, with possibly drunken vocalizations, decides to shoot his guns off in his yard, about a hundred feet from my table. I sometimes wonder if I’ll catch a stray bullet one day.

Still, it’s a place where I can come to do my work in solitude, and it keeps me sane.

It’s easy to fear that the rushing river of chaos may carry us away. Easy to fear our neighbors, some of whom not only shoot off guns in their yards but carry those guns to state capitols and cry fascist at governors who’re trying, under great pressure from both above and below, to enact sane public policy in the face of a plague. It’s easy to look at the ascendancy of lies and the suppression of science—specifically, in the pandemic, the suppression of medical expertise, which has sidelined the formerly trustworthy Centers for Disease Control and muzzled its prominent epidemiologists—and fear that the nation we’re living in has been transformed into a dystopia. While we slept. A dangerous quicksand where gestures made to protect the collective good are vilified by a leadership, and the shockingly large segment of the electorate that follows its lead, that confuses the democratic ideals of freedom with the right to do whatever it wants. And let the devil take the rest.

There’s nothing wrong with that fear, either. If anything we should embrace it. Fear is a reason to speak. I believe the languages our minds are made of—the languages of science, of math, of faith, of journalism, of music, of poetry, and of love—can, still and always, be marshaled to protect what we hold dear. Our families, our friends, the place we call home.

*

Being a fiction writer, naturally, I’ve always felt the made-up stories we tell are important and valuable. I’ve fondly referred to them as lies, saying I lied for a living. Yet fiction writers write toward truth as surely as other writers do, only using metaphor and symbol instead of data and reportage—my casual reference to lying was only possible because I trusted that readers knew fiction from nonfiction. (For one thing, when we publish and sell novels, we label them as such, right on the cover.) But recently I’ve lost that trust, and little quips about lies can’t be made anymore. These days, lying is serious business. Since much of the mainstream has come to embrace “news” that’s not news and “reality” that’s not reality.

On the news front, the dominance of a powerful media network that sells itself as information but is primarily a propaganda machine has blurred, and at times erased, the line between reporting and simply asserting with no evidence. And in the realm of straight-up entertainment, the genre known as “reality TV”—which of course is not a documentary form but simply an unscripted or less-scripted fiction, a heavily manipulated, staged, and edited performance of personality conflict—now commands a market share formerly commanded by genuine fiction. Some of it is entirely benign—cooking shows and athletic competitions, for instance—while the worst consists of bottom-feeding and tawdry soap-opera drama, replete with bikini-clad young women, bigoted duck hunters, and sociopathic abusers of tigers.

That embrace has produced a reality TV presidency that’s a spectacle of self-serving dysfunction, exactly like the shows from which it was disgorged. It’s a paradoxical spectacle: a government that professes to hate government but celebrates autocracy, an authority that rejects the idea of authority but claims its own is limitless. When allegations are made against it, it instantly deflects them by making the same allegations against its enemies, like a child in a nonsensical dispute who, if called a name, retorts, “No you are.” So far it’s gotten away with these tactics. Laughing merrily all the way to the bank.

Our conflation of entertainment with news has led us into a cultural landfill where garbage passes for food. Hungrily we stuff it into our mouths without noticing how rank it tastes, or that it’s burning our throats and cutting up our tongues.

*

In Norse cosmology there’s an immense tree called Yggdrasil that connects its nine worlds, including the worlds of ice and fire and ocean, of the giants and the gods, and of people. This tree of life is a mytheme: it appears across religions and cultures, throughout the globe and throughout human history.

“Yggdrasill, the Mundane Tree,” Baxter’s Patent Oil Printing, from a plate included in the English translation of the Prose Edda by Oluf Olufsen Bagge (1847).

“Yggdrasill, the Mundane Tree,” Baxter’s Patent Oil Printing, from a plate included in the English translation of the Prose Edda by Oluf Olufsen Bagge (1847).

To me the tree of life might also be seen as a tree of language, some of whose branches we understand and recognize, others of which, like a tree’s roots, run so deep, through processes so mysterious and complex, that they’re invisible to us—an intricate network of operating systems that extends throughout all living things. Language is profound and far-reaching and often unconscious, like the language through which our bodies know how to breathe and grow and heal without any conscious direction. We perceive only the ends and surfaces of the deep language of being, as they emerge to meet the air and light.

Right now this powerful force, this wellspring of both the sacred and the profane, is clearly being used as a weapon against us. And not just some of us, but all. Even those who don’t appear to recognize that their own welfare is under attack.

What occurs to me, as I sit down to write, is that this is the time to stand up for language. Not only to defend ourselves against the gibberish being tweeted out from on high, but to defend the truthful word itself from desecration.

Because without a public discourse tied to knowledge and to meaning, a common language we can rely on to settle arguments and negotiate our social differences, a time may come when we have no useful access to metaphorical weapons. Without a language for conflict resolution, some groups among us may resort—as anti-government cattlemen like the Bundys have, on a small scale, in recent memory—to literal weapons.

For those of us who love language more than guns, I’m thinking, now is the moment to deploy it. To act on the conviction that true words can rise again.

________________________________

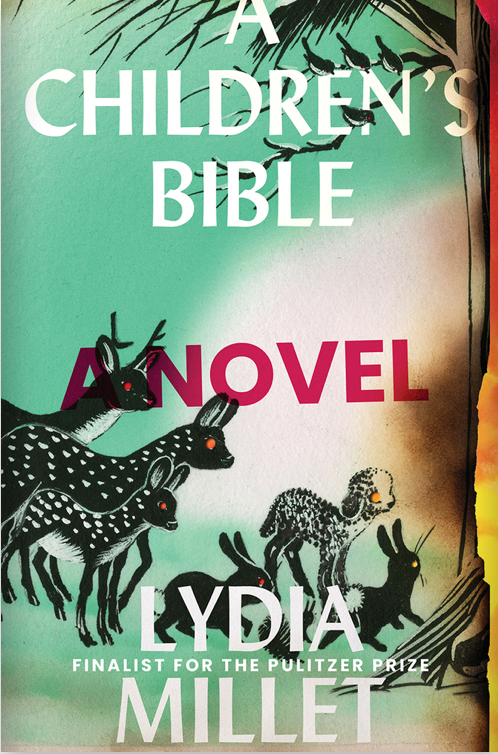

A Children’s Bible, by Lydia Millet, is available now from W.W. Norton.

Lydia Millet

Lydia Millet is the author of the novels Sweet Lamb of Heaven, Mermaids in Paradise, Ghost Lights, Magnificence and other books. Her story collection Love in Infant Monkeys was a Pulitzer Prize finalist. Her new novel is A Children's Bible. She lives outside Tucson, Arizona.