I went to the city because I wished to live recklessly, to front the nonessential facts of life, and see if I could not defy what I knew to be most true, and not, when I came to live, discover that I had never tried to die.

People came to New York, then, as now, to seek their fortune, but I had arrived on Veteran’s Day of 1980 in hopes of avoiding mine. There wasn’t much doubt in my heart that eventually I’d have to come out as trans, that in time I’d have to embark upon the path of transition and hormones and voice therapists and humiliating trips to the large-size shoe store. In the meantime, I hoped I could put all of this off for as long as I could, using the antidotes available to me in the forms of invention and fury to sustain what passed in my case for manhood.

Just be yourself!, we counsel the fearful. As if that’s so easy, as if being yourself is not the very thing that, once you’ve been unveiled, will get you murdered.

Thank goodness the world has changed so much since then, and everyone is now so much more compassionate and understanding about the complex challenges in the lives of trans and nonbinary people. Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha!

Henry David Thoreau was nobody to me then, maybe a name I vaguely remembered from AP American Literature, back at my supposedly all-male prep school in Pennsylvania. Later, at Wesleyan, I’d cleverly managed to avoid nearly the entire canon of American literature, with the single exception of a seminar I took on Herman Melville. I wasn’t a great student. Instead, I performed in a comedy group that had the misfortune to be everything except funny. One of our bits was about a group of elves who suffer from something called cocoa-lung.

In the Melville seminar we’d plowed our way through the whole bloody corpus, not just Moby Dick and Billy Budd and Bartleby, but some of the deep album cuts as well, including Pierre, or the Ambiguities, a story of sexual confusion and transgression. One New York review, back in 1852, had been titled (and I quote) Herman Melville Crazy. As an author I can be honest with you: this is actually not the kind of review you want to get.

I’d also read Hawthorne and Emerson in the Melville class—The Blithedale Romance, The Scarlet Letter, The American Scholar—but not Thoreau. Was I intentionally giving Henry David the slip? Was the idea of living in harmony with my own nature just too terrifying for young me? Yeah, probably, although in my own defense I would like to observe that it’s one thing to live an honest life by living in a little cabin and going fishing by moonlight, and it’s another to have to (for instance) have every one of the 30,000 beard follicles on your face burnt by an electrologist as you lie on your back screaming.

It’s not clear what drove Thoreau to the woods, at least not to me. He tells us, famously, that he’s hoping to live deliberately. “I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear.” Which is nice, I guess. But as in the case with another American hermit, Chris McCandless (whose story, of course, Jon Krakauer told in Into the Wild), there are always two narratives when it comes to such characters: there’s the one about living in harmony with nature and surviving on trout and moose-flesh (respectively), but there’s also the one in which these souls are on the run—from the people they love, from the spirit-crushing demands of the society, and from the yearnings of their own hearts.

When my daughter read Into the Wild in high school, I was struck by how gendered the student response was to McCandless’s journey. The girls in the class thought of him as a dashing idealist, a young man so committed to his ideal of freedom that he was willing to die for it. (This is largely the beatific view of him we get in Sean Penn’s film of the book.) The boys, meanwhile, uniformly thought of him as reckless, egotistical and deluded, a man who had killed himself and brought sorrow to those who loved him as a direct result of his ignorance of the true nature of wilderness.

It’s impossible for me not to wonder how much of Thoreau’s character was shaped by his inability to express what may have been in his heart.Thoreau’s contemporaries had mixed feelings about him, too. Elizabeth Hoar said, “I love Henry but I do not like him.” His stubborn contrariness seems to have sabotaged some of his friendships; Hawthorne described him as “manly and able, but rarely tender, as if he did not feel himself except in opposition.”

It’s impossible for me not to wonder how much of Thoreau’s character was shaped by his inability to express what may have been in his heart. Considering how often he’s held up as a queer icon, he rarely writes directly about his passions. There’s the far-off aroma of eros in some of his work, most notably in the elegy for 11-year old Edmund Sewell (“I might have loved him, had I loved him less.”) and his rapturous descriptions in Walden of the French-Canadian woodchopper Alek Therien. He never married, and he never had children—which definitely proves, you know: exactly nothing. So gay, maybe, but surely not gay as we think of it in the 21st century. In the end, all we can say for sure is that he had a secret self. “My friend is the apology for my life,” he writes mysteriously, in one of his journals. “In him are the spaces which my orbit traverses.”

Oh, Henry David. Who was this friend you orbited, and why did your love for him have to serve as an apology for everything else you did?

I would like to yell at Thoreau, to accuse him of failing to live up to the very demands he makes on the rest of us, but to be honest his inversion, and the melancholy it seems to have generated in him, is what I most relate to. Most of us can’t ditch everything to live alone in a cabin, much as we might like. But feeling afraid to obey the demands of your own heart? Fearing what might happen to you if you take the risk of living your own truth? Is there anything more human?

I know that I spent the first half of my life apologizing for my secret self. When I finally came out as trans I spent the better half of two years going around to everyone I’d ever known, begging for their forgiveness, pleading for their compassion. Please, I said over and over. I’m still the same person.

It’s one of the biggest contrasts between coming out as trans in 2020, and coming out 20 years ago, as I did. Most of the young people I know who come out now aren’t apologizing for anything. They enter their transitions with a sense of pride and fierceness, instead of—as was the case with me—the conviction that in becoming myself I had somehow let everybody down.

When I lost my hearing in my late fifties, I feared that my wife would divorce me; I assumed she’d find being married to a deaf woman like me annoying and intolerable. Instead she said to me, Jenny, I stayed with you through the gender thing. Do you really think I’d leave you because you have hearing aids?

In the same way I want to take Thoreau in my arms and whisper in his ear: Henry David, I stayed with you when you decided to live in a little cabin in the woods for two years. Do you really think I’d leave you because you had a crush on a woodchopper?

Thoreau grew up in Concord, then decamped for Harvard, where, among other things, he was a member of what eventually became the Hasty Pudding Club, and—according to legend—refused to pay the five-dollar fee for a diploma. “Let every sheep keep its skin,” said he.

I grew up in the farm country of Pennsylvania, in a ranch house surrounded by an enormous pine forest. There I played a game called Girl Planet, in which my rocket ship had crash-landed on an alien realm whose atmosphere turned you female. There was nothing you could do about it: it just happened.

I came to think of the woods as the place you could go to indulge a fantasy that could never come true. When I was a child, that fantasy was life as a woman. By the time I was in my early twenties, though, I was indulging a different fantasy—that in the city of New York I could instead sustain a life as a man and never have to take the risk of speaking the truth. If I were creative enough, and fast enough, and funny enough, it would be possible to live a man’s life. Or so I hoped. All I had to do was to devote myself to my art, what my grandmother ungenerously referred to as “the generation of blarney.”

For my first trick, I wrote a novel, entitled Ammonia Quintet, which was about a wizard who’s attacked by several waffle irons whom he has accidentally given the gift of life. The only way to fight the waffle irons off was by filling their mouths with batter, although he had to be careful to get the waffles out of there once they were done.

When were the waffles done? When the steaming stopped.

I undertook the writing of this novel in a marginal apartment on Amsterdam Avenue, a place I shared with my roommate, a young filmmaker named Charlie Kaufman. One night, as I teetered home from a bar called Paddy Murphy’s, I almost tripped over someone zipped up snugly in a body bag. Directly below our apartment was a health food store that sold no health food. But you could get a nickel bag there for 20 bucks.

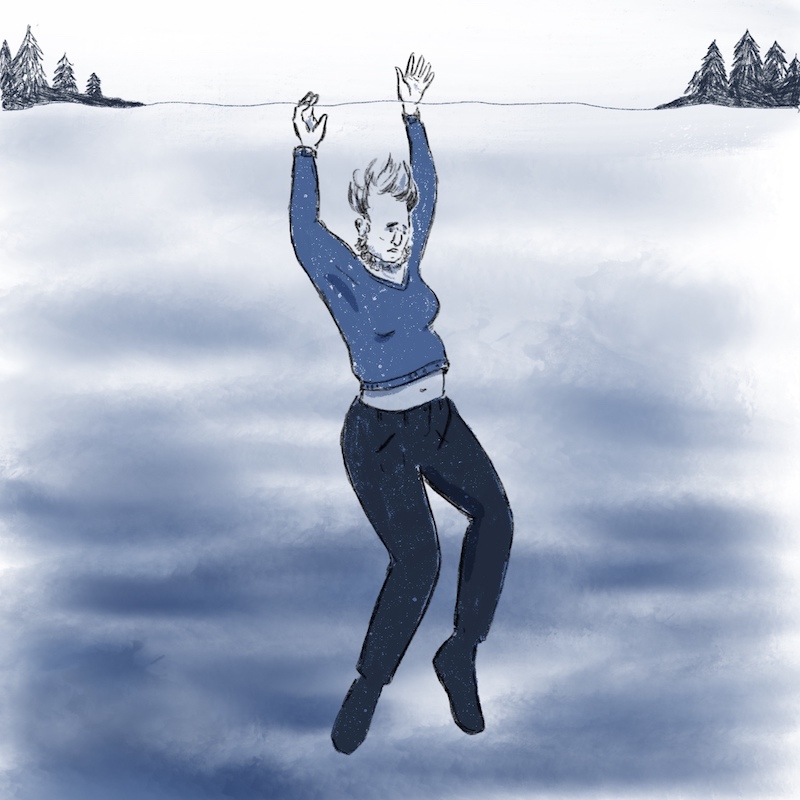

There were times when I thought of that dancing busty sweater as a metaphor for everything.Eventually I got a job in a mid-town bookstore where I sat most days beneath a sign that read ASK ME ANYTHING. Which people did. Once, a shopper asked me, Excuse me, where do you keep the Transcendentalists? I replied, They’re in with the literature. The shopper said, And where is the literature? I pointed to all the books on the shelves that surrounded us. It’s all around you, I said. It’s in front of you, it’s in back of you. It’s all we’ve got, is literature.

*

For Christmas, 1982, one of my friends, Beck Lee, gave all of his friends pets. I got a rabbit. It hopped around the apartment until I got sick of it, and gave it back to the pet store on Broadway.

The guy at the pet store wasn’t all that surprised. “Rabbits usually get returned,” he said, sadly. I had the impression that they only had the one rabbit, which they sold over and over again, like a fruitcake.

The following summer I received, as visitors, old girlfriends from college, Sarah and her friend Maeve, and man, did they rock my world. The women slept on my floor for the better part of a week, before they stepped on a train at Penn Station that would take them west. I’d noodled around with each of them, back at Wesleyan, but as usual it never went anywhere because unlike most of the boys (sic) that they knew, I was not all that interested in fucking. What I really wanted was to be in love—to be protected, to feel understood, to be safe. And like that.

What I loved about Maeve, in particular, was that she was that most mythical of creatures, the Cool Girl. What made her cool? For one, she arrived in New York City without shoes. The soles of her feet were as tough as those of hobbits, although unlike hobbit feet, of course, hers did not have hair on top. At least not back then.

For another, music just erupted out of her. One night, Maeve sat down at my upright piano and performed a 20-minute series of improvisations on the actual “Woolite Sweater Song,” a jingle from a television commercial from our childhoods that featured a haunted sweater that would come alive in the wash and dance around singing, You’ll look better in a Sweater washed in Woolite. Woolite washing makes a sweater come alive!

There were times when I thought of that dancing busty sweater as a metaphor for everything.

Back at Wesleyan, Maeve had been in a colloquium for her Classics major on Alexander the Great. A nervous boy was doing an oral report on the Amazons that day, and every time he said the word “Amazon,” she raised her shirt and flashed her breasts at him. Whenever she flashed him, she also said, Voop! Her poor victim, of course, had turned redder and redder, until at last he could not bring himself to say aloud the name of the main subject of his report.

“The-the-themiscyra was the name of their city,” he said, his index cards scattering on the floor.

“What was the name of their city?” asked their professor, one Andrew Szegedy-Mazak.

“Themiscyra,” he said, in a whisper.

“Whose city?” asked my friend Moynihan, knowing what the result of answering his question would be.

“The Ah—” He looked around the classroom in panic. Maeve was clasping on to the bottom of her shirt.

“The who?” said Moynihan. There was another frisson of laughter.

“The Ah—ah—ah—” He closed his eyes. “The Amazons!”

Voop!

On another occasion Maeve had gone for a few weeks where, on principle, she ate only pizza and drank only beer. This went on until she finally wound up at the college infirmary. What was wrong with her?

What was wrong with her was scurvy.

The doctors said it was the first case of scurvy they’d seen in 20 years. Maeve was embarrassed by this, but to the boys, it only deepened her legend. She had contracted scurvy, the same disease as actual pirates. For what purpose, or for whom, had she contracted scurvy? She had done it for us.

Many years later, Gillian Flynn had this to say, in her novel Gone Girl: “Men actually think this girl exists. Maybe they’re fooled because so many women are willing to pretend to be this girl. For a long time Cool Girl offended me. I used to see men—friends, coworkers, strangers—giddy over these awful pretender women, and I’d want to sit these men down and calmly say: You are not dating a woman, you are dating a woman who has watched too many movies written by socially awkward men who’d like to believe that this kind of woman exists and might kiss them.”

I did believe that these women existed, and I did kiss them. What I did not know was how hard it was to be such a woman, nor that coolness for girls was, at times, a performance that had to be sustained. It seems incredible to me now that I could have missed this obvious fact, given the daily performance of manhood that I was staging my own self.

But miss it I did. Maybe I should be less angry with myself for being blind when I was young. It is hard to see things clearly when you have not seen all that much. In lots of ways it is so much harder than being old.

Anyway, at the end of their week with me, Sarah and Maeve got on board a train to California. I got one postcard from them a week later. Funsters rocket westward, Maeve wrote. Are we there yet?

I didn’t get any more postcards after that. A little bit later I learned that Maeve had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital. And Sarah moved in with Moynihan, the youngest son of our Senator. He would die young, too.

As for me, I lay in my bed above the pot store, dreaming of things I knew to be impossible.

*

Two years later, I arrived in Boston a colorful scarecrow, having survived in the interim on a bowl of cereal and two slices of pizza every day. I was so thin that if you looked at my chest you could see my heart pulsing beneath my skin. In the meantime, I had written another novel. This one was called Anything Said Twice Is True. It was about a talented young man whose genius goes largely unappreciated.

Sarah had invited me to spend my birthday with her. She lived in a group home in Dorchester, one floor above a punk-rock band called The Stains, who were briefly famous for their single, “Give Ireland Back to the Snakes.”

I hadn’t seen Sarah since she headed west. I’d banished myself from her company—along with that of the other friends in her cohort—because I couldn’t stand to be a boy among them, and I couldn’t stand not to be one. But now all was forgiven. Where you been hiding, Boylan? asked Moynihan, handing me a beer for breakfast. It’s like you sailed off the edge of the world.

Alas, there was LSD in the beer, although I don’t know if Moynihan was the person who put it there. What I do know is that an hour or so later the whole world was made of softly pulsing rubber. Yellow lines floated and expanded on the floor, like ripples on a pond.

“Are you ready to go on the adventure now?” Sarah asked me.

“Werp,” I said, like tape running backwards in a reel-to-reel. Sure, I was ready to go on an adventure. Sarah gave me a piece of paper.

“Here’s the first clue,” said Sarah. It appeared as if we were going on a scavenger hunt.

The first clue instructed me to beware of falling glass, and to look for a frozen man. I didn’t know exactly what this meant, but falling glass, in the Boston of that day, meant the Hancock Tower, whose windowpanes had become famous for blowing out of their sashes in high winds and shattering on the sidewalk.

We got ourselves to Copley Square, where a statue of John Singleton Copley sat frozen on his pedestal. Pasted to the side of the pedestal was the next clue, which, once deciphered, sent me on to Old North Church. From there I was off to the Federal Reserve Building down by the harbor. And so on. Hours passed in this manner, finding clues, deciphering them, heading off to the next incomprehensible destination. In some ways it was a little bit like grad school.

In a Cambridge bar, The Plough and Stars, we were joined by another half dozen friends. It was a big crowd by now: Sarah and Moynihan, and Beck, the man who’d given me the rabbit I had to return. There was Nic, from my old comedy group, who smoked clove cigarettes. He coughed into his fist now and again, as if he’d come down with a case of cocoa-lung. There were other people there too—struggling musicians, struggling illustrators, struggling journalists. We drank a couple pints of Guinness and Moynihan told some dirty jokes and we sang some songs and the craic was good.

At first I thought this was the end of the journey—but then, when I went to the restroom, I saw another clue, written in marker above the john.

In short order we were off to the old Granary Cemetery, and the Grave of Mother Goose. I remember being shocked, when I arrived, that the woman’s name was actually Goose. She was the wife of Mr. Goose. The Gooses had been dead for a long time.

I suppose I will always be drawn to stories like that, tales in which someone’s secret self is kept hidden until the moment when it is at last safe to reveal the truth.Mother Goose’s headstone had an ornate skull etched into the top. It was a creepy boneyard, as these things go, but it was also full of celebrities: Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, John Hancock. Thoreau wasn’t there, though, of course: he’s over in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord. There he lies, next to Louisa May Alcott, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The clue at Mother Goose’s grave directed me to back to the street—where a car was waiting. Sarah was behind the wheel. “Now,” she said, “we’re off to Walden Pond.” The others followed in a half dozen vehicles of their own.

The drive to Concord took at least a half hour, maybe more. When we got there, the dozen of us did what to us seemed like the only logical thing, which was to take off all our clothes and dive into its peaceful waters.

Thoreau called Walden Pond—and lakes like it—“the landscape’s most beautiful and expressive feature. It is earth’s eye; looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature. The fluviatile trees next to the shore are the slender eyelashes which fringe it, and the wooded hill and cliffs around are its overhanging brows.”

I did not know whether I was gazing into the pond, or being gazed upon by it, when I got naked. The main thing that surprises me, looking back, is that we were so cavalier about stripping, not only because I hated being naked, but even more so because Walden is not exactly an unpopulated public space. Were we just unaware of the likelihood we’d be busted in the altogether? Was it that we just didn’t care? I don’t know.

My friends were better swimmers than I was, though, and before we reached the midpoint of Walden’s waters, they were swimming away from me. They were all on drugs, too, of course—but it still hurt my feelings, being left by those I loved to die.

My heart pounded. My feet felt like Smithfield hams. I was short of breath. I got a mouthful of water, coughed, flailed a little bit. Did my whole life pass before my eyes? Did I see a swirling montage of rabbits, Melville seminars, astronauts marooned on Girl Planet? Maybe. What I remember most clearly is being scared. This is what you get for living like this, I thought. You said you wanted to live recklessly, and to know what it is to try to die. Now you’ve got your wish.

My head sank beneath the surface, and I choked on a throatful of the sweet and peaceful water.

Then there was a woman next to me in the water. James, said Maeve. Where had she come from? She hadn’t been part of the scavenger hunt. She was naked too.

I stopped thrashing. The two of us treaded water for a little bit.

“Werp?” I said, my voice full of tears.

She looked at me with love. Werp, she said, and looked back at me with my own sad eyes.

Just like that, I was her, and she was me.

“You’re going to be all right,” I told the sad young man before me. For a few terrifying seconds, I was a Cool Girl, treading water. It was a lot harder than it looked.

In particular I remember that having breasts wasn’t that big a deal. In my pre-transition days, I’d thought it’d be amazing, having them. But they weren’t amazing, not really. They were just a fact.

*

A few hours later Maeve and I, along with the others, were standing in a long line at Steve’s Ice Cream in Harvard Square. We were back to ourselves by then.

There we stood, the dozen of us—bad playwrights, bad actors, bad guitar players, bad writers, waiting for our ice cream cones. Our hair was wet from Walden.

Maeve and I looked at each other with a sense of embarrassment now that we were back in our own bodies. I think each of us had thought, before the switcheroo, that the other one had a pretty good deal. But now we knew better. As Dick Van Dyke had observed in Mary Poppins, Life is a rum go, guv’nah, and that’s the truth.

The line for Steve’s went way down the block. There was a lot of talk about what kind of cone everyone was going to get when we finally arrived at the counter. There were Heath bar mix-ins and chocolate chunks and peaches and pistachios. There were sugar cones and waffle. Some of the tubs held sherbet. I stepped up and made my desires clear.

“I want a cone, please,” I said. “Vanilla.”

Moynihan mocked me for this. Really living on the edge there, Boylan. But Maeve defended me. “If you want a pure experience,” she said, “you want vanilla.”

A pure experience was what I wanted. Maeve and I went outside into the hot sun. Harvard students wandered around wearing Walkmen, listening to New Wave music. The ice cream began to drip down my hand, and I licked it. It was so sweet, so cold.

*

Five years later, I headed up to Nova Scotia to take my life. The way I figured, seriously, enough already. En route I’d called Maeve on the phone, told her I was passing through town on my way north. I wanted to make a good ending with her, to say goodbye to her with love. I felt bad that she’d saved me from drowning that time only to have me throw in the towel now. But that was the situation.

Maeve said, Okay, sure, let’s meet at 182 Smoots. Apparently there was a bridge over the Charles that had been measured out by MIT students using the height of a fraternity brother, one Oliver Smoot, as a unit of length. 182 Smoots was the halfway point.

I drove to Boston, parked my car, and then began to walk across the bridge, taking note of the Smoots as I proceeded. And soon enough, there she was: Maeve approaching from the opposite direction. She was still beautiful. Brown hair. Pink cheeks. Wicked smile. But I knew better by now than to conclude she was carefree. It was a full-time job, not being sad.

We reached the 182 Smoot point at the same moment, and wrapped our arms around each other, and kissed. We clutched on to each other like we were drowning. We didn’t talk. We kissed. I might have loved her more, had I only loved her a little less.

*

In Nova Scotia I experienced a very different kind of nature than the one I’d found in Walden Pond, or for that matter, back on Girl Planet. Cape Breton Island, in its fierceness, is not so unlike the Maine woods, and as I stood upon a precipice, preparing to plunge into the waters of the North Atlantic, I was not unlike Thoreau upon Katahdin, surrounded by swirling clouds and feeling “more lone than you can imagine.”

I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear.

At the moment of truth, though, a gust of wind had knocked me down, and instead of plummeting to my end, I lay there in the moss looking up at the blue sky. A voice in my heart said, You’re going to be okay. You’re going to be all right.

Afterwards, I would sometimes wonder whose voice it was I heard—the ghost of my father? My guardian angel? Jesus, the Savior?

Years later it occurred to me that this was the voice of my future self, the woman that I eventually became. But it is not lost on me that the person who first said these words to me was Maeve, the woman who had saved me from drowning in Walden Pond with a simple act of kindness. It was Maeve who showed me that I could rise above my sorrow, that I could live with fierceness and grace, if I could only find the courage to join the Amazons. Which in time, I did.

Voop!

*

On my way back from Nova Scotia, I stopped in at a party for my friend Beck, the rabbit-giver. The party wasn’t all that far from my old apartment in New York, the one which I had shared with Charlie Kaufman, one floor above the pot store. I was glad to see Beck again, in the wake of deciding not to do away with myself, but it’s one thing not to decide to stop being a ghost and another to become something solid. I was not yet out of the woods.

There were a lot of people jammed into the SoHo apartment that night, and at one point I slunk away from the throng and looked out the window in a dark bedroom. Everybody’s coats were piled up on the bed. A voice said, James Boylan? and I turned.

There was a girl named Deedie. She’d gone out with Nic at Wesleyan, back before he got cocoa-lung. I’d seen her now and again. Where did you go? she asked me. You were around, and then you were gone.

I told her I’d been up in Canada, wandering around the wilderness looking for something. Looking for what? she asked. Illumination, I said.

She nodded. After she’d been orphaned the year before, she’d climbed Mt. Rainier, looking for her own version of illumination. In her case this meant release from grief, solace from mourning. But halfway up the mountain, she said, she’d realized that this was not the place where she would find these things

No? I said. Then where do you find them then?

Deedie drew close and put one hand on my cheek. I know a place, she said.

*

In 2014, I gave a reading in New Hampshire for a community group that supported LGBTQ youth. Deirdre and I had been married for 26 years by then—12 as husband and wife, 14 as wife and wife.

She wasn’t wrong, when she said she knew where illumination might be found. It had been a long road, but we had traveled it together.

In the audience at the reading were a number of young trans and nonbinary people. It still amazes me, to gaze upon those young faces. What would my own life have been like, I wonder, if I’d had the courage to come out at 20? Or 15? Or ten?

It’s a trap, though, to fall into this kind of subjunctive thinking. Is there really any point in trying to live your life backwards? I had come out when I could—at age 40, in fact. I know this means that some of my life was wasted in sorrow, but on the other hand, being a boy was not only about sorrow. There were times when it was pretty fun. But even on the best days, manhood was always something I had to sustain through an act of will. Womanhood, now that I have crossed the valley, is simply there. The strangest thing about finally being myself is how little time I spend now thinking about what a miracle it is. Maybe I ought to, but I don’t. In the morning I just open my eyes, and shake off my dreams. Then I put my feet upon the floor.

But as I looked out into the audience that night, I saw a familiar face. It had been a long time, but she still had those apple cheeks, the look of mischief in her eyes.

In the morning, Maeve and I sat down by the quiet waters of a lake in New Hampshire with kpanlogos, a pair of African drums bedecked with beads.

Now I was female, and Maeve had become a master drummer. You never know about people. Here we were in the 21st century, and Maeve was determined to teach me how to drum in the style of the Ewe people of Ghana.

Incredibly, there was an abandoned steamboat moored in the lake right by the place we’d chosen to drum. I don’t know if it was just berthed there because it was the off season, or if this was its final resting place, or what.

It was hard not to think, as I gazed upon the hurricane deck and the pilothouse and the texas, of the wreck of the Walter Scott in Huck Finn, the boat upon which Jim and Huck discover the corpse of Huck’s father—even though it’s not for several hundred pages that Jim finally reveals the dead man’s identity.

I suppose I will always be drawn to stories like that, tales in which someone’s secret self is kept hidden until the moment when it is at last safe to reveal the truth. Jennifer, my memoir should have been called. Or, the Ambiguities.

I’m not all that good at drumming, to be honest, because in spite of being a very entertaining personality, I don’t have a very good sense of rhythm. As I drummed away, under Maeve’s instruction, I saw her wince a little bit, every time I missed a beat. Was it possible, here in my fifties, for me to finally learn how to keep time?

I hoped that my old friend did not miss the person I once was. Just as Jim said to Huck, concerning his father, He ain’t coming back no mo’ Huck. But then the person that she had been was gone too.

There we sat by the peaceful waters, drumming on our drums. I closed my eyes. When I opened them again, I’d return to the present, to the wrecked steamboat and the fallen world in which we had become two elderly women. But for a moment longer I kept my eyes closed, and there we were: two young people in love and in trouble, swimming across the waters of Walden Pond. It seemed like a long time ago.

Since those days, I had made my peace with Thoreau. I’d taught Walden to Irish students during my happy time as a professor at University College Cork, and I’d read The Maine Woods several times since my wife and I had moved to the state in 1988. There are some authors that we really shouldn’t read when we are young, and Thoreau may be one of them. All the advice on how to live your life can just seem exhausting when you’re a teenager, when you’re less concerned with living in perfect harmony with god than you are in simply keeping your head above water.

Or maybe it’s that I had come to understand that Thoreau and I had been wrestling with different versions of the same dilemma all along, what one Irish song calls the “turning of flesh and body into soul.” My life has been not unlike a scavenger hunt. Each clue has led to the next.

Thoreau says, “Every man is the builder of a temple, called his body, to the god he worships, after a style purely his own, nor can he get off by hammering marble instead. We are all sculptors and painters, and our material is our own flesh and blood and bones.”

I had written a couple novels during those New York Days, and since then, I have written more of them. But it turns out that stories are not really the things I have been writing. All these years the thing I have been inventing, draft after draft, is my own body. Isn’t that the best way of thinking of the way we constantly warp and morph—that all of us, in the end, are just works in progress, awaiting our next revision?

Maeve gave me a sudden smile, and then subtly changed the rhythm of what we were playing. She laughed, and I thought, what. I remembered that laugh from when we were young. It was a clear and joyful sound.

It made me so glad to be alive, and female, and unfettered, so glad for every mountain I had ever climbed, and every one I had since descended.

You’ll look better in a sweater washed in Woolite, my old friend sang.

It was love’s old sweet song.

A Woolite washing makes a sweater look alive.

__________________________________

Excerpted from the anthology Now Comes Good Sailing, edited by Andrew Blauner to be published by Princeton University Press on October 12, 2021.