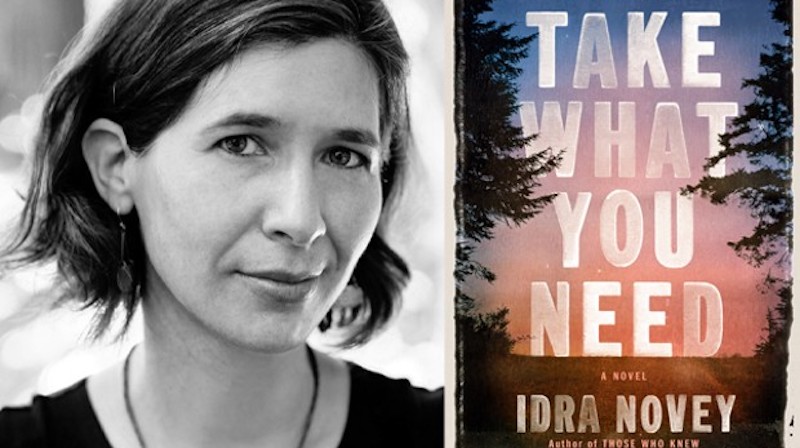

Idra Novey on Characters Who Hear and Mishear Each Other

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of Take What You Need

Idra Novey is poet and translator of works from the Spanish and Portuguese (including a Clarice Lispector novel) whose inventive novels transcend genres, emerging from our shared moment with authentic characters facing conflicts that are universal yet intimate. Her first novel, Ways to Disappear, the tale of a Pittsburgh-based translator who flies to Rio in search of a novelist who disappeared while climbing an almond tree, impressed me with its zesty comic touch and refreshing insights into the delicate processes and writing and translation.

I found her portrait of a charismatic bully who rises to political power in her second novel, Those Who Knew, bold and chilling. Take What You Need is a marvel of a complex mother-daughter story, and a parable of a self-taught artist whose visions overwhelm and redeem her. Our conversation spanned the continent.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How has your life changed during these past few years of turmoil and uncertainty? How has your writing been affected? Publication of this new novel?

Idra Novey: I lived in a one-bathroom apartment with four people during the pandemic. All night, I could hear the sirens from the ambulance dispatch down the street. Writing is how I stayed coherent, or at least closer to coherent than I would’ve been if I hadn’t returned daily to this novel. I looked forward to returning to Jean in her living room, welding with no regard whatsoever for the rest of the world. The book isn’t about the pandemic, but it is about how isolation changes people, and what art and risks feel more possible when you’re not anticipating the reaction and judgments of other people.

JC: What triggered the story you are telling in Take What You Need?

IN: The summer before the 2016 election, I started interviewing people I knew growing up about the portrayal of rural Pennsylvania in the news, what struck them as wrong or accurate. Although that was my initial question, many of the conversations ended up being about estrangement, painful impasses they’d reached with relatives and friends over political disagreements.

I’m interested in blind spots, why people write each other off.I thought those frank conversations might find their way into a memoir, or maybe an oral history of political polarization in Appalachia. At the time, I was reading Svetlana Alexievich’s magnificent oral history of people from Chernobyl. The more interviews I did, though, the more my imagination took over and fictional scenes began to occur to me, focused on just three characters, a young man who’s unemployed and ends up working for an artist living next door to him, the complex chemistry between them, and the artist’s estranged daughter, who’s left the region.

JC: How does the Appalachian setting reflect your own background?

IN: I was born in the Allegheny Highlands of southwestern Pennsylvania. My mother and grandmother were also born there. Parts of my family have lived in that region for over a hundred years. My namesake Ida Novey started a scrapyard in her front yard with my great-grandfather Abe in 1906. They were immigrants and collecting what other people discarded was the only viable job option they had. This novel became a way to connect with my namesake, who never learned to read or write in English.

JC: What made you decide to make this narrative a two-hander—alternating between Leah, who grew up in a small town in the Allegheny Highlands and now lives in Long Island City with her husband Gerardo and toddler son Silvestre, and her “complicated” former stepmother Jean, who has lived in the same town all her life.

IN: I’m interested in blind spots, why people write each other off. It’s so easy to delete someone online, but what if that person devoted nine years of her life to raising you? I wanted to write about the psychic cost over time of that kind of estrangement for someone like Leah, who likes to think of herself as empathic, but is in fact quite limited in her ability to understand Jean’s reality, surrounded by vacant houses and the sound of gunshots at night.

Jean meanwhile has never left the country and has no idea how living in Peru might have changed Leah’s outlook on the world. I enjoyed alternating between their perspectives and writing about the vast cultural distance between where I grew up and where I live now. This novel allowed me to pursue a number of questions about art in this country, whose work we are inclined to value and at what age.

JC: Which voice came first, Leah or Jean? Which was easiest?

IN: Jean came first and was much easier to write. Among the many people I interviewed in my hometown for this book, I met Helen Golubic, who travels to flea markets all over Appalachia and makes stunning collage pieces out of cigar boxes. I joined Helen when she set out at 4:30 in the morning on many flea market adventures and we’ve become close friends. Jean is an invented character, but Helen’s dynamic voice, her determination to find art and beauty in unexpected places helped me figure out the driving force of this book.

Leah’s voice was more elusive. She’s a composite of various people and her husband Gerardo is as well. Their family is different from mine in substantial ways, but what I did draw from my own life were moments when I was in Pennsylvania, speaking Spanish in public with my family. Most strangers unaccustomed to hearing Spanish in that area ask questions out of curiosity in welcoming, respectful ways, but not always.

JC: What sort of research was involved in telling the story of Jean, who becomes a sculptor inspired by Louise Bourgeoise and Agnes Martin?

IN: Louise Bourgeois entered the novel after I found a beat-up copy of her collected writing at Bull Creek, the flea market that Jean goes to in the novel. Bourgeois’ insights on sexuality and power, on the psychic hold her father continued to have on her, aligned potently with how I imagined Jean’s artistic drive. Bourgeois recognized the libidinal forces that compelled her to keep taking new risks with her art. Agnes Martin’s writing aligned with Jean’s process in other aspects. Martin, like Jean, felt a strong need to retreat and work in complete solitude.

While writing Jean’s chapters, I immersed myself in the writing of Anne Truitt, Celia Paul, Hilma af Klint, and many other women artists, too, who were repeatedly dismissed and written off, and yet somehow still found the conviction to keep taking their art seriously. One of the most deeply joyful and rewarding processes of my writing life has been trying to understand Jean’s nerve, why she keeps getting on her father’s ladder, stacking her Manglements as high as the ceiling of her living room allowed.

Before starting the novel, I learned to weld. I wanted to get a physical sense of Jean’s choices and how she’d go about making her Manglements. I also just wanted to torch things and I still meet up to weld with the Brooklyn-based metal artist Julia Murray and with Norman Ed, a Syrian American sculptor in Appalachia I’ve been visiting in his studio for many years. I wrote a profile of Norm’s extraordinary work for Orion.

JC: Jean’s creative process is filled with surprises. In creating her massive “Manglements,” she works with scrap metal, spoons, objects found at flea markets. She breaks a mirror, and sees a way to incorporate shards of mirrored glass into her work. Does this happen with your own work? Did it happen while working on Take What You Need?

IN: What a fascinating question and observation, and yes, that parallel you intuited, between Jean’s impulse to make art out of the mirror she shattered and my own instincts with this novel, is spot on. I came to fiction from poetry and the only way I know how to proceed is in slivers of language. I felt an ongoing sense of synchronicity with Jean’s sculptures, where the railroad spikes I imagined her seeking for her towers got me experimenting with barbed words and subtle “spikes” I could incorporate into the sentences of the scene.

The only way I know how to proceed is in slivers of language.JC: Jean’s neighborhood deteriorates in the course of your story, with many condemned buildings. Elliott, the teenager next door, becomes central to her life, including helping her during some artistic breakthroughs. Elliott is struggling with poverty and addiction. How did you work through Leah and Jean’s differing responses to Elliott?

IN: I tried to stay in perspective, to inhabit each character’s physical and emotional response to Elliott as complexly as I could. I read authors who I found particularly skilled at inhabiting characters without imposing any authorial moral agenda. Claire Keegan, for example, writes with such refreshing restraint. She doesn’t pass judgment on her characters. She lets the dialogue and interactions speak for themselves. With Leah and Jean, I tried to stick to the private logic of each one, what their unspoken fears would compel them to say—or not say. In my conversations with friends about why they’d chosen to stop speaking to certain relatives and neighbors, what people couldn’t say out loud often revealed what pained them the most.

JC: What is your fiction writing routine? How do you fit writing novels into your life, in teaching at Princeton, translating (what is your most recent project?), writing poetry.

IN: I start each day with several mugs of tea. Sometimes I need half a mug to assemble half a sentence and it’s a full two cups of tea before I reach a punctation mark. I also like to mumble through what I wrote the day before to hear it aloud. When I’m working on a translation, I mumble through both the original and whatever lines I’ve recreated of it in English, and over time that habit has now become part of my routine when working on my own writing as well. I’m not currently working on a book-length translation, though I did recently translate a story by Chilean writer Nona Fernandez, and I’ve been co-translating some poems by Spanish poet Luis Muñoz with Garth Greenwell.

JC: What are you working on now?

IN: I have a few poems I’m working on, and I wrote a possible opening of a new novel while I was in Chile over the holidays visiting my in-laws. I find it easier to figure out new fictional voices in English when everyone around me is speaking Spanish. I’ve started all three novels in Chile. Switching between languages is a reminder that none of us have just one default voice. What makes fiction fascinating is the limitlessness of voices any one author can invent to experiment with how people in any given era or place might hear, and mishear, each other.

__________________________________

Take What You Need by Idra Novey is available from Viking, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.