Iconic Blues Musician Bobby Rush Remembers His Rocky Relationship With James Brown

”If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.”

In 1957, I was making $7.50 a night at a joint called Walton’s Corner. That was top dollar for me. Walton’s Corner had a gigantic neon sign in the shape of a T, with “Walton’s” in the top of the T and “Corner” in the stem of the T. With showplace written at the bottom, it was impressive-looking for the neighborhood it was in. That bright sign stuck out like a church steeple. It was one of the better blues spots around. In the fall, I invited Sonny Thompson over to my show. He loved it. I was just hitting my stride with a show that was well paced with just the right number of blues, slow songs, and early R&B hits. I wanted to impress Sonny ’cause he was kinda like the Chicago hookup to King and Federal Records based in Cincinnati.

“Bobby Rush, man, I been telling James (Brown) about you. I’m bringing him tomorrow night.”

I was excited. James Brown had not become James Brown yet, as in the Godfather of Soul, but music folks knew him far and wide as a dynamic performer—with some badass hair and a badass band. “Please, Please, Please” was out on Federal Records—but it wasn’t that big signature song of his yet. James showed up with two other cats from his Famous Flames band. The drinks were flowing and the conversation lively. After my set, James only had one question. “Bobby Rush, what do you put in your hair?” I said, “A little bit ah conk and a little bit ah love!” Everybody fell out laughing.

Sonny Thompson always knew I was seeking some kinda break—maybe even to get on King Records. So in trying to be a big shot that night, I told the bartender that I would buy a round of drinks for them.

My happiness was short-lived, for I found out that James had put three more rounds on my tab. My bill was $112. It would take me months to pay back Mr. Walton. That pissed me off. Real bad. When I saw James, maybe a few days later, I said, “Mane, y’all put me in a trick Saturday night.” I didn’t threaten him, but I was trying to squeeze some sympathy and maybe some money out of him. James said only one sentence to me.

I was excited. James Brown had not become James Brown yet, as in the Godfather of Soul, but music folks knew him far and wide as a dynamic performer—with some badass hair and a badass band.

“Mane, if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” He laughed.

“What do that mean?”

“Mane, if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” He laughed some more.

But it wasn’t funny to me. Not at all.

Years passed and I guess I opened for James Brown maybe ten or twelve times, and we became friends (not close friends, but friends). We talked about remaining as independent as possible. And women. James had lost two or three fortunes over his career to the usual suspects: poor management and, of course, the old favorite, the IRS. In 1968, the IRS said James owed them $2 million.

Fast-forward to 1991. James was getting ready to be released from prison. He served three years of what was a six-year stretch for aggravated assault and running from the cops. Pervis Spann, who was his friend and all-around good guy, came to me with a proposition. We would produce “James Brown’s First Show” out of a prison in Atlanta, Georgia. It required us to put up $30,000. Fifteen from me, fifteen from Pervis. I didn’t have money, so I went to the bank to borrow it. If we filled up a little more than half the venue, we’d be in good shape. I could double my money—easy.

But James screwed us, and I lost my shirt. I felt stupid—so motherfuckin’ stupid. When I called James, he said, “Mane, if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” The same line he had said to me thirty-four years earlier. I lost my respect for him after that—because he showed me no mercy at all. Maybe he shouldn’t have—hell, I put up my own money, and in 1991 I should have known better. As the years passed and the sting of that lesson wore off, I do have fonder memories of James. He would always say, “There’s only one James Brown and there’s only one Bobby Rush. So don’t do me, just do you.”

I knew in life that sometimes you’re the windshield and sometimes you’re the bug. Still, I always took chances—flying close to the edge. I called it having hope or investing in myself. But hope can be like a hen that lays too many eggs. Losing that bread over James Brown was a hard motherfucking lesson. I would have to learn to take chances on things I had more control over. And the only thing I had control over was me.

__________________________________

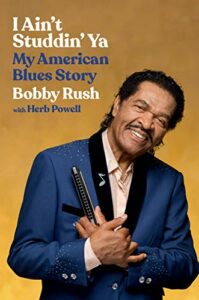

Excerpted from I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya: My American Blues Story. Used with the permission of the publisher, Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Bobby Rush with Herb Powell.

Bobby Rush

Bobby Rush is a Grammy award-winning blues musician who has recorded over 400 songs over the course of five decades in the music industry. He is a Blues Hall of Famer, a 13-time Blues Music Award winner, and a B.B. King Entertainer of the Year. I Aint't Studdin' Ya is his first book.