Ice and Inspiration: An Ode to Writing in Winter From Val McDermid

Why the Coldest Season of the Year Helps Fuel the Creative Process

I’m not a person who sets much store by rituals. I don’t have to put my left sock on before my right; I don’t have to write longhand in a Moleskine notebook of a particular size; I don’t care in what order the milk and coffee come together in my mug, even though I’ve been told that they form different colloids.

But I do have one habit that probably falls into that category. I like to start this year’s novel on January 1st. Even if it’s only a couple of paragraphs, it’s enough of an act to convince me I can do it again. Which is never a given, even after forty published novels. My Ne’erday habit is a way of keeping that fear at bay.

Of course, saying I start the book on January 1st isn’t really true. By the time I compose those first sentences, I’ve spent hours, days, weeks and months finding the narrative that is strong enough to carry me through the process of creating a novel. I’ve walked for miles around my local nature reserve, or on the Fife Coastal Path, or along the banks of the Water of Leith in conversation with my characters, teasing out the idiosyncrasies of their speech patterns, testing how they navigate conversations, deciding how they will react in moments of crisis or revelation.

I love winter. I love its contrasts….I love the peace of the nature reserve with its labyrinths of bare branches and its startling sunsets.

I can never predict what will set the wheels turning initially. Sometimes it’s a tangential nugget in a podcast or a radio program or a platform talk that provokes the “I never knew that!” moment. For example: over the course of a talk about crime in the Lake District in the 18th and 19th centuries, I learned that William Wordsworth and Fletcher Christian (of Mutiny on the Bounty notoriety) had attended school together; that the Lake District had no effective law enforcement back then; and that there had been a strong and persistent rumor that Fletcher Christian had not perished on Pitcairn Island alongside the other mutineers but had returned to the Lakes where he’d been protected from prosecution by friends and family.

These three apparently disconnected facts exploded in my head and, after a lot of research, formed the narrative engine of The Grave Tattoo, a contemporary thriller with its roots firmly in the tail end of the eighteenth century.

Sometimes it’s a life experience that I know I want to write about, but I don’t have the story to go with it yet. There are many of those, but the one that comes immediately to mind is the Miners’ Strike in the UK in the mid-eighties. I was still a journalist then, but I also had a visceral understanding of what was at stake. My grandfathers had both been miners whose early deaths owed much to their working lives. And I also understood the bonds that held those tight-knit communities together. I knew they were not going to win this fight and I knew defeat would not satisfy Margaret Thatcher’s government and that the price they’d extort would be catastrophic.

But I wasn’t a published fiction writer yet and I knew I’d have to serve a lengthy apprenticeship before I’d be able to bring that story to life in a book that wasn’t just a political rant or four hundred pages of special pleading. And when I found that story—A Darker Domain—the catalyst that brought it into existence came on a Tuscan hillside where we stumbled on a ruined casa collina that was the subject of an inheritance dispute and thus available to squatters. But when we found it, the squatters had departed, clearly in a hurry, for they’d abandoned clothes, a silk screen printer and a bundle of event posters in the style of German expressionism.

Sometimes the book arrives thanks to someone else’s anecdote. Sometimes circumstance turns the kaleidoscope to reveal another design for living, like the COVID lockdown (Past Lying). And sometimes an idea grabs me and I nurse it for years and it never springs to life. But it still might, one day…

Once I know the shape of the story, I know what I need to know that I don’t know yet. Often that drives me to the National Library of Scotland. More often it drives me into the arms of an expert—someone whose life revolves around what I need to know, whether that’s a captain of a barge plying the waterways of Europe (The Last Temptation) or a mountaineer (Trick of the Dark), or what happens when torrential rain falls on a road embankment (Silent Bones).

Then I take my characters for walks and hope they’ll be talkative enough to be ready to roll on January 1st.

That’s not a random date on the calendar. When I started writing full time, back in 1991, I was writing two books a year. I needed to pay the bills, but it was also practically possible. There were almost no literary festivals or bookstore events. If I was lucky, I’d pick up the occasional library gig, which paid for a couple of weeks’ groceries! Also, I was writing books that grew directly out of my own world—Lindsay Gordon, a Scottish journalist, and Kate Brannigan, a PI based in Manchester, where I lived and worked. I didn’t have to do a lot of research…

I’m not so keen on the damp grey days, I admit. So It’s no hardship to stay at my desk.

Once I’d learned how long it took to get the words down when I no longer had the inconvenience of a job, I counted backwards from my delivery date to when I needed to start writing. It didn’t take many books before I found the flaw in my method—during the warm summer months when I wanted to be outdoors, walking in the hills or hosting barbecues or enjoying sybaritic holidays, I was sweating over my keyboard. Writing meant I was actually missing out on the experiences and encounters that fueled my imagination.

And so I decided to stop thinking about delivery dates and start writing when there was much less FOMO in my life! Don’t get me wrong—I love winter. I love its contrasts (Indoors: big jumper, Nordic socks, reading by a blazing fire with a wee glass of whisky. Outdoors: down jacket, windproof trousers, alpaca scarf and Sherlock Holmes hat with ear flaps). I love the peace of the nature reserve with its labyrinths of bare branches and its startling sunsets. I love the blitz of wee birds at the feeders in the garden. I’m not so keen on the damp grey days, I admit. So It’s no hardship to stay at my desk.

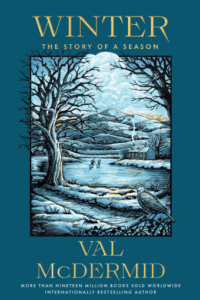

It also means I have time at other points in the year for saying “yes” to unexpected offers. That “yes” stops me getting stuck in a rut. I’ve found different voices and different styles that have made me reach higher and wider and I’ve loved what I’ve learned. Queen Macbeth offered the chance to upturn the potent myth in Shakespeare’s play. Resistance allowed me to speculate about a lethal pandemic before it actually hit. This latest “side gig,” Winter, turned into a privileged opportunity to write about a different kind of love.

So bring it on. I’m open to offers!

__________________________________

Winter: The Story of a Season by Val McDermid is available from Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.

Val McDermid

Val McDermid’s bestselling novels have won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Mystery/Thriller, and the Crime Writers’ Association’s Gold Dagger and Cartier Diamond Award for outstanding achievement. The Karen Pirie novels have been adapted into an Edgar Award-nominated ITV/BritBox show. She is also a five-time finalist for the Edgar Award, including Fact Crime nominee Forensics and most recently the Sue Grafton Memorial Award nominee Past Lying. She lives in Scotland.