Ibtihaj Muhammad: Finding a Home in the (White) World of Fencing

"Everything around me seemed like a dream. Fencers that looked like me."

We heard about this place in New York City specifically for Black fencers. Since I’d started fencing, other parents had casually mentioned it to my mom when she was in the stands at my competitions, thinking she might be interested in checking it out since we were Black. After my disappointing performance at the Junior Olympics, my mother decided it was the perfect time to try to find some more information about this club people kept talking about. We both thought this might be the place where I could get some extra help and training.

With only a little bit of digging, my mother discovered the name of the organization was the Peter Westbrook Foundation. Through sheer coincidence, around the same time Mom was doing her research on the club, a documentary film about Peter Westbrook himself was premiering in New York City. My mother took that as a good sign and decided to take Faizah and me into the city to go see the film.

Peter Westbrook’s story was a fencing fairy tale that unfolded right in our backyard of Newark, New Jersey. The child of a Japanese mother and an African-American father, Peter and his younger sister were raised by his mother alone in a housing project in Newark during the 1950s and 60s. As a child of mixed-race heritage and during a time when race relations were tense due to the burgeoning civil rights movement, Peter struggled with his racial identity, and his mother worried that without a father figure in his life, he would turn to the streets for answers. In Japan, his mother’s paternal heritage included a long line of men of the sword—samurai—and these men held an honorable role in society. Peter’s mother wanted the same for her son and thought fencing could provide a similar sense of honor and pride. More importantly, she felt it would provide an outlet for his energy and a safe space from the Newark streets. Once Peter’s mom found out there was a fencing team at his high school, she begged her son to try out for the team. As a high school freshman, Peter had already discovered the importance of the street hustle, so legend has it that he struck a deal with his mother. He agreed to try fencing if his mother paid him five dollars. His mother agreed, so Peter went to the team practice after school. Secretly Peter enjoyed the sport, but he didn’t tell his mom that. Instead he told her he wasn’t yet convinced. She offered him another five dollars if he went back, and he built a small bankroll until he couldn’t deny he had found a true passion. As a saber fencer, Peter excelled on his high school’s fencing team and was recruited with a fencing scholarship to attend New York University, one of the best collegiate fencing schools in the country.

Peter’s stardom only continued to soar from there. In his first year in college, he won the NCAA title for a saber fencer. By the time he was a college senior, he had become the national champion, an honor he would repeat twelve more times over the course of his career. In 1976, he attended his first Olympics. By his retirement from competitive fencing, he had been to five Olympic competitions, winning a bronze individual medal in 1984. During his last Olympics, in 1992, he was selected to carry the torch for Team USA. It wasn’t just his success as a fencer that made Peter Westbrook so remarkable, though; it was also the fact that he came from such humble beginnings and still managed to dominate a sport that had previously been reserved for the white and wealthy. He battled opponents on the strip and was forced to fight racism and classism in order to claim his spot among the annals of fencing greats, which he did on his own terms. Peter claimed the title of being the first ever African-American to win a national gold medal in saber fencing.

“Seeing all of those Black people in the room was such a contrast to what we were used to seeing in the world of fencing.”

Once he retired from competition, Peter Westbrook didn’t hang up his saber. Knowing how fencing had saved him from a life of dead ends, he decided he wanted to help other young kids without a lot of advantages. At the urging of a friend, Peter created the Peter Westbrook Foundation in 1991 in midtown Manhattan. The idea was to use fencing to not only teach a remarkable full-body sport, but also to teach life skills to underserved children from the New York City area. What started as a small program for fewer than a dozen kids ballooned into a powerhouse operation serving more than 250 kids from the community, plus an elite athletic program created to train young athletes with potential to fence on the national and international circuit. Pretty soon, the Peter Westbrook Foundation had developed an international reputation as the place where good fencers of color go to become great.

When the film was over, I had tears in my eyes. Our stories were similar. We were both born in Newark. We were both rarities in fencing—Peter for his race and me because I wore hijab. Peter had reached a level of success I could only dream about at the time, but I still felt an instant kinship with this bald-headed, brown-skinned, petite, wiry fencing elder. There was a reception after the film, and we had a chance to meet Peter and some of his coaches. I was so nervous I didn’t know what to say when it was our turn to shake his hand. Luckily my mother didn’t have the same problem. She knew exactly what to say. She told Peter that I was a saber fencer, that I attended Columbia High School, and I was looking for a way to improve my game. My mom may have been unsure of the differences between saber and épée, but she knew how to help her children get ahead. And sure enough, Peter told my mom to bring me to the foundation on any Saturday morning, and they’d be happy to see what I could do.

Mom and I took the train into New York City’s Penn Station on an unseasonably cool day in May. It was toward the end of my junior year of high school. We then walked down to 28th Street and Seventh Avenue. The Peter Westbrook Foundation was housed on the second floor of a nondescript building not too far from the Fashion Institute of Technology. The foundation shared the space with the New York Fencers Club where elite athletes from around the city also practice. We took the elevator up and entered into a huge space dominated by hues of blue. Bright blue walls and pillars extended down the floor. The smell of sweat and metal hit us as soon as we entered. The sound of fencing blades clashing and loud chatter filled the room. Mom and I paused in amazement as we entered the space. This was the largest fencing club I’d ever been in, and almost everyone there was some shade of brown. And there were a lot of people. Dozens of little brown kids were getting fencing lessons from coaches who were also brown.

There were some white, Latino, and Asian kids on the floor as well, but the overwhelming majority of students seemed to be African American. My mother and I stood there for a moment taking it all in. We turned to each other at the same time and grinned.

“Can you believe this?” I whispered to my mom.

Seeing all of those Black people in the room was such a contrast to what we were used to seeing in the world of fencing. I felt like a five-year-old at Disneyland. Everything around me seemed like a dream. Fencers that looked like me. Coaches that looked like me. I could feel the tension in my shoulders release as an immediate sense of belonging settled over me. To walk into a room full of fencers and not feel like the odd one out, to not feel eyes surveying my body, pausing at my hijab, wondering if my race or religion would prove an impediment to my success on the strip, felt like freedom.

![]()

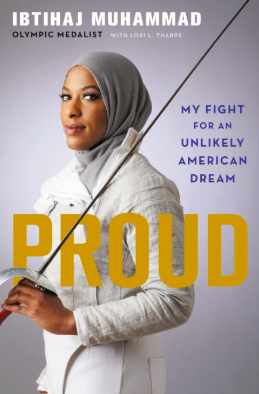

From Ibtihaj Muhammad’s Proud, courtesy Hachette. Copyright 2018, Ibtihaj Muhammad. For the young readers’ edition, head here.

Ibtihaj Muhammad

Ibtihaj Muhammad is a fencer and the first Muslim American woman in hijab to compete for the United States in the Olympic Games. She is also the first female Muslim American to medal at the Olympic Games, winning bronze in the women’s saber team event. Named one of TIME magazine’s 100 Most Influential People In the World, she serves as a sports ambassador for the U.S. State Department, cofounded Athletes for Impact and the clothing company Louella, and inspired the first hijabi Barbie in her likeness.